Maxillofacial and plastic surgery

Vol. 44: Issue 6 - December 2024

Low condylectomy and functional therapy alone for unilateral condylar osteochondroma treatment: case report and literature review

Abstract

Osteochondroma (OC) is a common bone tumour that rarely affects the mandibular condylar process. This pathology can show typical clinical features, such as facial asymmetry, deviation of the chin and dental inferior midline, changes in condylar morphology and malocclusion with an increased posterior mandibular vertical height. The management of condylar OC is a debated topic among surgeons. Most of them combine systematically condylectomy with orthognathic surgery while only few others perform in the first instance only condylectomy followed by functional therapy. A case of a 32-year-old female diagnosed with a mandibular condylar OC successfully treated with condylectomy alone is presented. A literature review is carried out focusing on surgical management, clinical and imaging features, highlighting the differences between OC and other condylar growing lesions.

When maxillary alterations are not present or are mild as in the presented patient, the low condylectomy alone, followed by elastic functional therapy, can correct both the aesthetic and the occlusal disorders resulting from condylar OC removal. In case of severe dentoalveolar maxillary compensation, orthognatic surgery must be performed with the low condylectomy to quickly correct facial symmetry and occlusion.

Introduction

Bones can be affected by primary benign or malignant tumour and metastatic lesions 1-3. The osteochondroma (OC), also called osteocartilaginous exostosis, is the most common benign bone tumour in the body, representing 35 to 50% of all benign bone tumours and 10-15% of all primary bone tumours 1,2. It is extremely rare in cranio-facial area where it can involve the skull base, maxillary sinus, zygomatic arch, and mandible. In the last one, the coronoid process and the condyle are more often affected 4. OC is usually a solitary tumour even if it can be multiple as in hereditary multiple osteochondromas (HMO) disorder.

OC is described as slow-growing cartilage-capped bony projection on the external surface of the bone, containing a marrow cavity that is continuous with that of the underlying bone 5. This cartilaginous cap can be a few mm thick or even absent in the inveterate tumour with slow growth 6.

Clinically the condylar OC can cause facial asymmetry and occlusal disorder. Being the growing vector of osteochondroma predominantly vertical, the prognathic deviation of the chin and malocclusion with open-bite on the affected side and cross-bite to the contralateral side, are the typical clinical features.

Quite frequently when the osteochondroma becomes relatively large, it may disarticulate the affected condyle out of the mandibular fossa, mimicking a bigger mandibular lesion and worsening the facial asymmetry.

The differential diagnosis of condylar OC includes benign or malignant tumours 7 and hyperplastic mandibular pathology.

The aetiology of these lesions is unclear and several hypotheses have been proposed 8. Often this tumour arises in the condylar anteromedial aspect, at the lateral pterygoid muscle insertion. For that reason some authors supposed that continuous muscle stress may cause hyperplastic overgrowth of embryonic cells with cartilaginous potential 9. Other theories and studies identify the cause in periostium defects which left herniate the cartilage 10. Previous mandibular trauma seems also associated with condylar OC 11.

It can develop at any age but 80% of cases occurs in adolescence or young childhood, with female preponderance (male to female ratio of 1:1.85). OC must be considered as a true neoplasm rather than a hyperplastic pathology: mutation of the EXT gene is involved in the tumour pathogenesis 12. It is a not-self-limiting neoplastic growth and, if untreated, a progressive worsening of the facial asymmetry is expected.

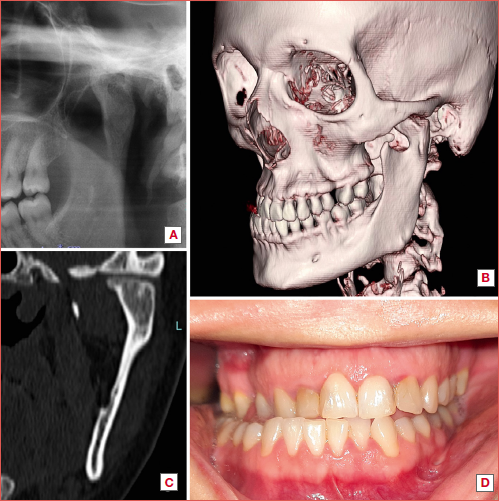

For diagnosis, clinical evaluation and imaging of first (panoramic radiograph) and second level (computed tomography [CT] and technetium-99m scintigraphy) are required (Cover figure).

Surgical excision by condylectomy is the treatment of choice, with or without associated maxillary-mandibular surgery, depending on the entity of concomitant facial and occlusal changes, patient’s expectations and surgeon’s habits.

OC, like other hyperplastic mandibular pathology producing a caudal displacement of the mandible, can lead to compensatory modifications in the maxillofacial bones and dental structures. This may dictate the adjunctive use of orthognathic surgery procedures to restore facial aesthetic and dental occlusion.

The most dangerous drawback of osteochondroma is its sarcomatous transformation which usually happens within the cartilage cap and leads to the development of chondrosarcoma 13. Solitary osteochondromas have a 1% risk of malignant transformation whereas in the HMO cases, this value increases by 10 times 14. To date no malignant evolution has been described in the condylar process. A case of chondrosarcoma histologically arisen from an osteochondroma of the nasal septum is the only reported malignant transformation of a craniofacial osteochondroma in the literature 15.

However, it remains difficult to clearly ascertain which amount of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) chondrosarcomas derived from a condylar OC and which part of them arose as chondrosarcoma de novo from the very beginning 16.

In the following case report, we will illustrate the management of a condylar OC, treated with condylectomy alone and will discuss the surgical treatment choices by collecting and comparing other evidence from the literature.

Case report

A 32-year-old female was referred to the Unit of Maxillofacial Surgery of IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, Pavia, Italy. One year before presentation, the patient began to feel intermittent pain in the left TMJ region, followed by a progressive and worsening mandibular and chin right deviation, with loss of dental relationship. No pain on the contralateral TMJ was reported. Clinical examination revealed marked facial asymmetry, with chin and mandibular deviation to the right side, 12 mm from the facial midline. An 8 mm lower right dental midline deviation to the facial midline and an asymmetrical prognathism were noted (Fig. 1). The interincisal mouth opening was 35 mm, but lateral movement to the right was clearly restricted. No canting of the maxillary occlusal plane or dentoalveolar compensation was noted. After repositioning the inferior arch on the left side, the dental casts analysis showed good occlusal stability.

A slight posterior open bite on the left side was present with a crossbite on the controlateral side (Cover figure D, Fig. 2). It appeared that the lesion had caused a more anterior translational movement of the condyle, rather than a purely vertical growth.

A hard mass was palpable under the zygomatic arch, below the level of the articular tubercle; the glenoid fossa was empty and no condylar movement was felt during mouth opening. A panoramic radiograph showed a longer and thicker left mandibular condyle, if compared with the unaffected side, with the same radiopacity as the adjacent bone (Cover figure A, Fig. 3).

A high resolution CT scan was performed to better visualise the lesion, its extension and possible relationship to adjacent cranial or vascular structures. It showed a bony prominence arising from the anteromedial surface of the left condylar process at the site of insertion of the lateral pterygoid muscle. This mass extended superiorly and medially towards the infratemporal fossa, where it formed a pseudoarticulation with the skull base. The glenoid fossa was empty (Cover figure B, C; Fig. 4).

Technetium-99m scintigraphy was also performed as a diagnostical tool. It revealed abnormal tracer uptake in the left TMJ, without other intense focal areas of tracer concentration in the rest of the skeleton, demonstrating an increased metabolic activity in the left condylar process. It is important to underline that scintigraphy, although highly sensitive, is a non-specific diagnostic examination: the result of hyperactivity is not necessarily related to active growth, as it can also be found in infection, trauma or in other neoplastic diseases. Only together with full clinical and radiological evaluation, the scintigraphy helps to differentiate between a growing and a non-growing lesion.

On the basis of clinical and radiological examination, a suspected condylar osteochondroma was diagnosed.

The patient was operated under general anaesthesia with naso-tracheal intubation. Arch bars were applied, and an endaural incision with temporal hockey stick like extension was performed. The superficial temporal fascia and periosteum overlying the zygomatic arch were incised and the dissection continued to the TMJ capsule. The joint capsule was incised and the condylar head and neck were dissected. An osteotomy was carried out with a 2.3 mm fissure burr (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI, USA) remaining in healthy bone, caudal to the condylar head (Fig. 5A). The lesion was removed en bloc, preserving as much unaffected bone tissue of condylar neck as possible. The specimen measured 1.8 x1 x 2 cm (Fig. 5B).

The individual occlusion was restored performing maxillomandibular fixation (MMF) with 0.4 mm wire; the residual condyle position was checked and found to be slightly anterior and caudal, not perfectly seated in the glenoid fossa. After removal of the MMF, the occlusion showed a light anterior and contralateral open bite with mild posterior occlusal interference, sign of reduced posterior vertical height. Nevertheless, it was decided not to proceed with mandibular ramus surgery, due to the limited vertical dimension loss and the predicted functional remodelling.

The condylar stump was not reshaped and a hole was made in its posterior aspect. The displaced disc was repositioned over the new condyle and fixed to it with absorbable stitch (Monocryl 5-0 Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA) passing through the hole. Finally the joint capsule was closed with absorbable sutures (Vicryl 4-0 Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA), a drain was placed and the wound closed in layers by Vicryl 4-0 and Etilon 6-0 (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA).

The patient progressed well and was discharged on the second postoperative day after a CT scan (Fig. 6).

After surgery light elastics were used for 6 weeks to guide the occlusion without intermaxillary fixation. Early mobilisation is one of the most important factors in preventing possible TMJ ankylosis and restoring TMJ function. The patient was followed up once a week and trained in the use of the elastics. The arch bars were removed and a 4-week programme of functional physiotherapy including jaw exercises was recommended to increase the amount of jaw opening and lateral movements. Unfortunately, the patient refused to undergo to rehabilitation. Histopathological examination of the resected specimen confirmed the diagnosis of osteochondroma.

There were no postoperative complications in terms of infection or bleeding. A transient paralysis of the temporal branch of the facial nerve was noted, which completely resolved within 3 months. Complete correction of the mandibular, chin and inferior incisal midline deviation was achieved (Fig. 7). The contralateral crossbite and ipsilateral posterior open bite were resolved (Fig. 8). The occlusion did not require any additional orthodontic treatment after surgery. Mandibular function was partially impaired: the maximal incisal opening was greater than 40 mm, although with deviation in mouth opening to the left and limited lateral movement compared to the unaffected condyle. However, this did not affect the patient’s quality of life. A new CT scan 16 months after surgery revealed remodelling of the condyle, with no evidence of recurrence (Fig. 9).

Discussion

A commonly recommended treatment for condylar OC is surgical excision of the lesion with a portion of the unaffected mandibular condyle to ensure complete removal of the pathological entity. In general, if there is evidence of abnormal condylar growth, then condylar surgery should be performed before a severe dentoalveolar maxillary compensation develops 17.The most preferred surgical approach is the “high” preauricular incision 18-20 with or without temporal extension, depending on the dimension of the lesion. In case of a very large tumour on the medial condylar aspect, the zygomatic arch osteotomy can be associated to improve surgical field 21. Similarly, a temporary condylar base osteotomy after preplating can be made to gain space towards the infratemporal fossa 22. More recently an endoscopic-assisted intraoral approach has been described 23. In this case report the preauricular approach was used and a low condylectomy alone, without orthognathic surgery or any other surgical procedure, was performed. Local excision 24, conservative condylectomy or total condylectomy have been reported as possible treatments for condylar OC. Total condylectomy, which significantly reduces the height of the posterior mandible, must be accompanied by condylar reconstruction with a costochondral graft or a total joint prosthesis. Regardless of the method used, total condylectomy increases operative time, morbidity and costs with less predictable results. Therefore, total condylectomy cannot be recommended as a routine procedure in all cases.

Conservative condylectomy can be high or low. In the former, the horizontal osteotomy is usually done 4-5 mm caudal to the edge of the condylar head, leaving a portion of the condylar head intact. High condylectomy is the treatment of choice in hemimandibular hyperplasia and elongation in a growing condition 25.

On the contrary, in OC treatment, high condylectomy, together with local tumour excision, seems to have a higher risk of recurrence 24,26. However, from our literature review, these recurrences seem to be very rare, with only three cases reported to date 27.

The so-called “low condylectomy” involves an osteotomy line below the head but high in the neck, preserving its entire length and ensuring a radical tumour excision 26. Removal of the tumour with a small portion of unaffected condyle seems to be the gold standard for treatment of condylar OC, avoiding recurrence and preserving as much as possible the posterior vertical dimension.

The amount of condyle to be resected depends on the extent of the tumour and on the infiltration of the condyle: usually the OC involves only a limited portion of the condylar head, so the unaffected part of the condyle should be preserved. Certainly, if the condylar neck is also involved by the tumour, total condylectomy must be performed along with reconstruction 18.

Most surgeons systematically combine condylectomy with orthognathic surgery, stating that the loss of posterior height caused by condylectomy must be corrected by an ipsilateral mandibular sagittal split or vertical osteotomy 11,26,28,29.

More recently some authors have reported good outcomes with condylectomy as the sole treatment for condylar OC 11,30-32, following the principle of “proportional condylectomy”, firstly described by Delaire 33: the amount of condyle to be resected is determined by the vertical difference between the two ramus heights measured from the mandibular angle to the highest point in the condylar region. In their opinion, after surgery, functional therapy with light elastics is sufficient to correct aesthetical and occlusal disorders.

Therefore, different approaches to treat condylar OC are used depending on the entity of facial and occlusal changes, patient’s expectations and surgeon’s habits.

The lack of consensus about this pathology does not facilitate the surgical treatment choice. Some surgeons have classified the OC as a type of condylar hyperplasia 26 which puts it on a par with hemimadibular hyperplasia (HH) 25.

Other authors clearly distinguish OC from HH and from solitary condylar hyperplasia (SCH) 25,34. In all these three pathologies the condyle is increased in size, but while in HH and SCH the condylar head often maintains its normal shape, in OC it appears extremely irregular 24 and may even form a pedunculated tumour several centimetres in size. In HH and SCH this bone protrusion is less common.

According to Obwegeser 25 HH is a three-dimensional anomaly of the mandible, involving the condyle, ramus and body, and terminating at the midline.

A more recent paper points out that HH always involves the ramus and the body, resulting in increased height, whereas this does not happen in the OC. Except for the condylar region, the two sides of the mandible are symmetrical in OC 34.

Although these two diseases have similar aspects in terms of clinical manifestations and histological description, immunohistochemistry clearly indicates a higher rate of proliferative activity in condylar OC 35, which is a sign of faster growth.

Even if both pathologies can lead to morphological changes due to dentoalveolar maxillary and mandibular compensation, this does not happen in case of faster tumour growth (OC), at least initially. As a result, the most frequent clinical signs of condylar OC are unilateral posterior open bite on the affected side, deviation of the mandibular midline, and unilateral posterior crossbite on the contralateral side. This is probably the reason why, in the majority of condylar OC reported 30, the maxillary canting was mild or even not observed. In this situation, the compensatory change in the maxilla does not occurs or is negligible 36.

In case of slower growing lesion (HH), we usually assist to a vertical growth of the maxilla on the ipsilateral side with canting of the occlusal plane, as a compensatory mechanism to accommodate the increased vertical mandibular dimension. However this dentoalveolar compensation also occurs in a long-standing or undiagnosed faster growing lesion: early diagnosis and tumour resection are necessary to prevent it.

In the recent published literature, the majority of OC are treated by low condylectomy with articular disc repositioning combined with orthognathic surgery, either simultaneously or separately 11,26,28,29. In fact, after low condylectomy, a variable mandibular vertical height decrease is expected: the sagittal mandibular split or vertical ramus osteotomy allow to set back the residual condylar stump into the fossa and to completely repair the vertical posterior dimension.

However, especially in OC patients, in whom the two sides of the mandible are symmetrical 31 and in whom no compensatory mechanism has yet occurred, adding orthognathic surgery to the condylectomy in all cases can be considered an overtreatment, even though effective.

More recently, some authors reported the use of condylectomy without orthognathic surgery as the sole treatment in condylar OC 11,30-32,37-39, followed by functional therapy, with good aesthetic and occlusal outcomes. Farina et al. 31 plans on the panoramic X-ray the amount of condyle to be removed from the affected side (proportional condylectomy) so as to match the height of the contralateral mandibular ramus. This principle seems to be the way to go 31,40 although it has been controversial in a recent systematic review 41.

However, while this proportional resection seems to be more feasible in the HH, in whom a minimum of 4-5 mm high condylectomy is required, the authors believe that this is not always achievable in OC, where a lower resection is advisable. In the presented patient, the length of the ramus was approximately 72.2 mm on the affected side and 66.2 mm on the unaffected side (Fig. 10). To perform the low condylectomy as described previously, 10 mm of condylar height had to be removed. The new postsurgical vertical dimension of the ramus became 62.2 mm, 4 mm less than the healthy contralateral ramus (Fig. 10). In order to perfectly match the length of the healthy side, we should have reduced the resection to 4 mm, performing a high condylectomy and exposing the patient to a greater risk of recurrence.

Accordingly, it was preferred to remove the tumour with safe margin, performing a low condylectomy and accept the loss of vertical dimension. Clinically this resulted in dental interference on the affected side and an open bite on the contralateral side, which can be corrected with immediate intermaxillary elastic therapy followed by physiotherapy. The dentoalveolar movements (dental intrusions on the affected side and extrusions on the healthy side) and the functional remodelling of the resected condylar stump, together with neuromuscular adaptations, are involved in this process 37,40-43. Indeed, the new CT scan at 16 months after surgery, compared with the immediate postoperative CT, revealed remodelling of the condyle and intrusion of the teeth on the affected side with a significant reduction in the articular dead space. The musculoskeletal system adapts to this reduced vertical dimension of the mandible (Fig. 9).

The limitations of this procedure are not well known. The amount of vertical dimension loss that can be corrected with this functional approach is difficult to say: the need of reconstruction to restore occlusion and TMJ function is widely recognised in case of total condylectomy, although precise data are still lacking for less radical resection. Similarly, in case of maxillary canting, correction with condylectomy and elastic therapy only is well described 31,37 but the maximum amount to be corrected with this approach is not reported. With classic orthodontic treatment dental extrusion occurs within a few weeks, while intrusion of the posterior teeth takes several months 42 and may require excessively prolonged treatment. Curiously, in the patient presented, posterior dental intrusion took place in just 6 weeks with complete occlusion correction. We can assume that the posterior dental interferences after condylectomy, with the use of arch bars and elastics therapy, are able to accelerate the posterior teeth intrusion. Further studies are needed to establish a surgical protocol with indications and limitations, referring to the treatment of condylar OC with condylectomy alone, although the adaptive capacity of the masticatory system is highly variable between patients and unfortunately not well predictable 43. In addition, orthognatic surgery can still be performed in case of persistent malocclusion or facial asymmetry 6 months after low condylectomy.

Conclusions

In selected patients without pre-existing facial deformity or severe dentoalveolar compensation and when the tumour involves a limited part of the condylar process, low condylectomy alone without subsequent orthognathic surgery seems to be the preferred treatment option for condylar osteochondroma, avoiding more invasive surgery and the associated risks. The immediate postoperative malocclusion caused by the deficiency in ramus length, if present, can be corrected by functional therapy with elastics, followed by physiotherapy. To date the limitations of this approach in terms of vertical dimension loss and canting of occlusal plane are not well known and further research is needed to highlight them. Moreover, the need for early diagnosis and surgical treatment should be emphasised, as long-standing OC may involve larger condylar portion or show severe dentoalveolar compensatory changes that can only be corrected with the addition of orthognatic surgery.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

DS: conceptualization, writing original draft, reviewing manuscript, supervision; SM, RP: writing original draft, reviewing manuscript, editing; SL, GB, GS: reviewing manuscript; LP: imaging analyses, reviewing manuscript; FS: orthodontics consideration, reviewing manuscript, all authors: clinical discussion and literature review.

Ethical consideration

The research was conducted ethically; the patient has filled out informed consent before carrying out the instrumental investigations and surgery, in accordance with current European regulations, agreeing to voluntary participation in the study and publication of data in anonymous form.

History

Received: June 20, 2024

Accepted: September 24, 2024

Figures and tables

Figure 1. A) Submental view of this 32-year-old woman presenting with facial asymmetry. The chin was shifted 12 mm to the right and the left mandibular border was positioned approximately 10 mm more caudal; B) frontal view with patient’s smile: cross bite on the right side with markedly displaced chin and inferior midline to the right.

Figure 2. Dental occlusion and maxillary occlusal plane without canting. The inferior midline has been shifted 8 mm to the right.

Figure 3. Panoramic radiograph showing longer and thicker left mandibular condyle.

Figure 4. CT 3D reconstruction: the mass extends towards the infratemporal fossa, arising from the anteromedial surface of the condyle which is dislocated from the glenoid fossa. The inferior dental and mandibular midlines are displaced to the unaffected side. A) Frontal view; B) left lateral view.

Figure 5. A) High preauricular approach for condilectomy; B) condylar OC removed.

Figure 6. CT 3D reconstruction one day after tumour resection: the resected condylar stump is set back towards the mandibular fossa. The individual occlusion restored with arch bars and light elastics. A) Frontal view; B) left lateral view.

Figure 7. The patient shows good facial symmetry. A) Frontal view; B) submental view.

Figure 8. Postoperative stable occlusal relationship.

Figure 9. CT 3D reconstruction, left lateral view 16 months after surgery.

Figure 10. CT 3D reconstruction with measurement of the ramus length: A) preoperative right lateral view; B) preoperative left lateral view; C) postoperative left lateral view one day after surgery.

References

- Huvos A. Bone Tumors: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prognosis. Saunders; 1979.

- Dahlin D, Unni K. Bone Tumors. General Aspects and Data on 8542 Cases. Charles C. Thomas Pub; 1986.

- Marelli S, Ghizzoni M, Pellegrini M. Lung cancer cells infiltration into a mandibular follicular cyst. Case Rep Dent. 2023;17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/7297821

- Karras S, Wolford L, Cottrell D. Concurrent osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle and ipsilateral cranial base resulting in temporomandibular joint ankylosis: report of a case and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;54:640-646. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0278-2391(96)90652-7

- Khurana J, Abdul-Karim F, Bovée J. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. (Fletcher C, Unni K, Mertens F, eds.). IARC; 2002.

- Schajowicz F. Tumors and Tumor-Like Lesions of Bone and Joints. Springer-Verlag; 1981.

- Bernasconi G, Preda L, Padula E. Parosteal chondrosarcoma, a very rare condition of the mandibular condyle. Clin Imaging. 2004;28:64-68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0899-7071(03)00100-1

- Brien E, Mirra J, Luck J. Benign and malignant cartilage tumors of bone and joint: their anatomic and theoretical basis with an emphasis on radiology, pathology and clinical biology. II. Juxtacortical cartilage tumors. Skeletal Radiol. 1999;28:1-20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s002560050466

- Weinmann J, Sicher H. Bone and Bones. Fundamentals of Bone Biology. Mosby; 1955.

- Hwang S, Park B. Induction of osteochondromas by periosteal resection. Orthopedics. 1991;14:809-812. doi:https://doi.org/10.3928/0147-7447-19910701-16

- Roychoudhury A, Bhatt K, Yadav R. Review of osteochondroma of mandibular condyle and report of a case series. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:2815-2823. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2010.10.016

- Porter D, Simpson H. The neoplastic pathogenesis of solitary and multiple osteochondromas. J Pathol. 1999;188:119-125. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1096-9896(199906)188:2%3C119::aid-path321%3E3.0.co;2-n

- Douis H, Saifuddin A. The imaging of cartilaginous bone tumours. I. Benign lesions. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41:1195-1212. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00256-012-1427-0

- Bovée J. Multiple osteochondromas. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-3-3

- Barrett A, Hopper C, Speight P. Oral presentation of secondary chondrosarcoma arising in osteochondroma of the nasal septum. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;25:119-121. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0901-5027(96)80055-5

- Giorgione C, Passali F, Varakliotis T. Temporo-mandibular joint chondrosarcoma: case report and review of the literature. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2015;35:208-211.

- Chen Y, Bendor-Samuel R, Huang C. Hemimandibular hyperplasia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97:730-737. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199604000-00007

- Lim W, Weng L, Tin G. Osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle: report of two surgical approaches. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2014;4:215-219. doi:https://doi.org/10.4103/2F2231-0746.147151

- Al-Kayat A, Bramley P. A modified pre-auricular approach to the temporomandibular joint and malar arch. Br J Oral Surg. 1979;17:91-103. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0007-117X(79)80036-0

- Sfondrini D, Marelli S. The “low preauricular” transmasseteric anteroparotid (TMAP) technique as a standard way to treat extracapsular condylar fractures. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2024;52:108-116. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2023.11.001

- Kumar V. Large osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle treated by condylectomy using a transzygomatic approach. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39:188-191. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2009.12.004

- Liu X, Wan S, Abdelrehem A. Benign temporomandibular joint tumours with extension to infratemporal fossa and skull base: condyle preserving approach. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;49:867-873. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2019.12.009

- Yu H, Jiao F, Li B. Endoscope-assisted conservative condylectomy combined with orthognathic surgery in the treatment of mandibular condylar osteochondroma: a retrospective study. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25:1379-1382. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/scs.0000000000000862

- Peroz I, Scholman H, Hell B. Osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle: a case report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;31:455-456. doi:https://doi.org/10.1054/ijom.2002.0234

- Obwegeser H, Makek M. Hemimandibular hyperplasia hemimandibular elongation. J Maxillofac Surg. 1986;14:183-208. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0301-0503(86)80290-9

- Wolford L, Movahed R, Dhameja A. Low condylectomy and orthognathic surgery to treat mandibular condylar osteochondroma: a retrospective review of 37 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;72:1704-1728. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2014.03.009

- Peroz I. Osteochondroma of the condyle: case report with 15 years of follow-up. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;45:1120-1122. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2016.04.005

- Martinez-Lage J, Gonzalez J, Pineda A. Condylar reconstruction by oblique sliding vertical-ramus osteotomy. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2004;32:155-160. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2003.12.006

- Holmlund B, Gynther G, Reinholt F. Surgical treatment of osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle in the adult: a 5-year follow-up. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;33:549-553. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2004.01.006

- Kim J, Ha T, Park J. Condylectomy as the treatment for active unilateral condylar hyperplasia of the mandible and severe facial asymmetry: retrospective review over 18 years. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;48:1542-1551. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2019.06.022

- Fariña R, Pintor F, Perez J. Low condylectomy as the sole treatment for active condylar hyperplasia: facial, occlusal and skeletal changes. An observational study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44:217-225. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2014.10.013

- Villanueva-Alcojol L, Monje F, González-García R. Hyperplasia of the mandibular condyle: clinical, histopathologic, and treatment considerations in a series of 36 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:447-455. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2010.04.025

- Delaire J, Gaillard A, Tulasne J. The place of condylectomy in the treatment of hypercondylosis. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 1983;84:11-18.

- Sun R, Sun L, Sun Z. A three-dimensional study of hemimandibular hyperplasia, hemimandibular elongation, solitary condylar hyperplasia, simple mandibular asymmetry and condylar osteoma or osteochondroma. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2019;47:1665-1675. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2019.08.001

- Yu J, Yang T, Dai J. Histopathological features of condylar hyperplasia and condylar Osteochondroma: a comparison study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-019-1272-5

- Herbosa E, Rotskoff K. Condylar osteochondroma manifesting as Class III skeletal dysplasia: diagnosis and surgical approach. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1991;100:472-479. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0889-5406(91)70088-e

- Fariña R, Moreno E, Lolas J. Three-dimensional skeletal changes after early proportional condylectomy for condylar hyperplasia. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;48:941-951. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2019.01.016

- Nolte J, Schreurs R, Karssemakers L. Demographic features in unilateral condylar hyperplasia: an overview of 309 asymmetric cases and presentation of an algorithm. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2018;46:1484-1492. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2018.06.007

- Kim D, Kim J, Jeong C. Conservative condylectomy alone for the correction of mandibular asymmetry caused by osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle: a report of five cases. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;41:259-264. doi:https://doi.org/10.5125/2Fjkaoms.2015.41.5.259

- Mouallem G, Vernex-Boukerma Z, Longis J. Efficacy of proportional condylectomy in a treatment protocol for unilateral condylar hyperplasia: a review of 73 cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2017;45:1083-1093. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2017.04.007

- Niño-Sandoval T, Maia F, Vasconcelos B. Efficacy of proportional versus high condylectomy in active condylar hyperplasia – a systematic review. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2019;47:1222-1232. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2019.03.024

- Nitzan D, Palla S. “Closed Reduction” principles can manage diverse conditions of temporomandibular joint vertical height loss: from displaced condylar fractures to idiopathic condylar resorption. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;75:1163.e1-1163.e20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2017.01.037

- Ellis E, Throckmorton G. Treatment of mandibular condylar process fractures: biological considerations. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:115-134. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2004.02.019

Downloads

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright

Copyright (c) 2024 Società Italiana di Otorinolaringoiatria e chirurgia cervico facciale

How to Cite

- Abstract viewed - 596 times

- PDF downloaded - 305 times

PDF

PDF