Rhinology

Vol. 44: Issue 4 - August 2024

Management of frontal sinus and frontal recess inverted papilloma: our experience and systematic review

Abstract

Objective. For frontal sinus inverted papilloma (FSIP) management, an endoscopic endonasal approach (EEA) can be combined (or not) with an external approach by an osteoplastic flap (OPF) or with a more conservative open approach. The present study aims to describe our experience in the management of FSIP, focusing on disease-related and anatomical features influencing outcomes and recurrence.

Methods. This case series of FSIP investigated anatomical and disease-related predictors of recurrence associated with EEA or a combined EEA-OPF approach. A systematic review was also performed, selecting publications on IP with the insertion point in the frontal sinus or frontal recess.

Results. Among 30 patients included, 18 underwent EEA, while 12 received a combined EEA-OPF approach. During a median follow-up of 37 months, the frontal sinus was cleared of IP in all cases except 2 in the EEA group, who presented a complex posterior wall shape of the frontal sinus. From the systematic review, a combined EEA-OPF approach was associated with a lower risk of recurrence.

Conclusions. A correct indication for a combined EEA-OPF approach is paramount and should integrate all disease-related and anatomical features, including posterior wall shape.

Introduction

Sinonasal inverted papilloma (IP) is a benign epithelial tumour classified as part of the sinonasal Schneiderian papilloma category and represents 0.4-7% of all sinonasal tumours. It is characterised by local aggressiveness, high rates of recurrence, and possible association with carcinoma 1, so that a complete surgical IP resection with the drilling of the bony insertion point is mandatory 2. Extension and origin of the lesion (preoperatively assessed through computed tomography [CT] scan and magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] investigation with a 74-90% accuracy in pedicle identification) 3 are the main parameters to consider when tailoring the approach and extension of surgery 2. The lateral nasal wall is the most common attachment site identified, followed by the maxillary and ethmoid sinuses; the frontal sinus, nasal septum, and sphenoid sinus are infrequent sites of origin 3.

Frontal sinus IP (FSIP) is a rare pathology and represents only 2.5-5% of all cases of IP, but is associated with a higher risk of recurrence compared to other sinonasal insertion points 4,5. As previously reported 6, this pathology should be treated with an endoscopic endonasal approach (EEA) whenever possible, due to reliable outcomes and reduced morbidity compared to open approaches 7. However, unfavourable anatomy with difficult exposure of the tumour’s pedicle can require a combined approach 8. In 2019, Pietrobon et al. 9 proposed a list of contraindications for an exclusive EEA to reduce the risk of recurrence.

In a trend of trying to push the limits of an exclusive endoscopic approach, this study aims to understand when exclusive EEA is not advisable, analysing personal experience reported in a case series and a thorough review of the literature, which is lacking on this topic.

The present article focuses on disease-related and anatomical features that can influence surgical resection of FSIP and challenge an exclusively endoscopic approach; among these, the role of posterior wall shape is highlighted.

Materials and methods

Case series

A retrospective single-institution case series of FSIP was evaluated in the present study. In detail, patients affected by frontal sinus and frontal recess IP were included. IP with the insertion point in other ethmoidal structures or sinonasal subsites (with the frontal sinus and frontal recess involved by extension only without any insertion) were excluded.

All patients underwent clinical examination with nasal endoscopy, preoperative biopsy, and MRI and CT, which provided information about posterior wall shape, lateral extension of the frontal sinus, anterior-posterior nasofrontal recess extension, and interorbital distance.

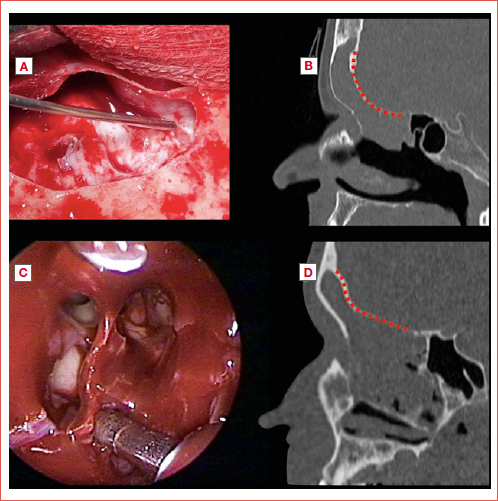

Posterior wall shape (Fig. 1) was classified as: 1) “straight configuration”; 2) “C-shaped configuration” (or “curved configuration”) if two components (one vertical and the other horizontal) formed one angle; 3) “S-shaped configuration” if 3 segments (one proximal vertical segment, one median more horizontal, one distal vertical) formed two angles. Antero-posterior nasofrontal recess diameter (Fig. 1) was calculated by measuring the distance between the frontal beak and the posterior wall of the nasofrontal recess. The distance between the nasion and the posterior wall of the frontal sinus was also recorded, referring to the possible antero-posterior extension of a frontal sinusotomy extending the drilling to the entire frontal beak up to the nasion 9. The lateral extension of the frontal sinus was classified as small, medium, or large if extended in its widest diameter respectively to the medial, central, or lateral third of the orbital roof, respectively (Fig. 2) 10. The interorbital minimal distance was calculated by measuring the minimal distance between the medial wall of the two orbits 9.

From a surgical point of view, the resection targeted the pedicle insertion, performing EEA (with Draf IIb or Draf III procedures) or a combined EEA-osteoplastic flap (OPF) approach in case of extensive tumour or complex anatomy.

Surgical information included IP insertion, presence of intracranial invasion, and surgical approach used.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 24 (IBM Corp. in Armonk, NY, USA). Data are reported as median ± interquartile range (IQR). Fisher’s exact test was used to evaluate the association of posterior wall shape, lateral frontal sinus extension, and intracranial invasion with the recurrence of the IP. A Mann-Whitney U test was used to verify the association of interorbital distance and anterior-posterior nasofrontal recess diameter with recurrence rate. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Systematic literature review

A systematic review was performed in accordance with the Meta-analyses Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines. The systematic review was completed in April 2022 through research in the PubMed and Scopus databases using the research string “(Inverted papilloma [mesh] OR Inverted papilloma [tiab]) AND (frontal sinus [mesh] OR frontal sinus [tiab]))”.

A Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO) framework was used to elaborate a review question for which all components would be defined. The following question was formulated: in patients with FSIP, what are the surgical approaches and their relative recurrence rate described in the literature?

A selection was performed including publications on IP with the insertion point in the frontal sinus and the frontal recess, excluding patients with IP affecting the frontal sinus by contiguity. Studies in which cases with FSIP were mixed with other tumor locations were excluded. Case reports were not included.

Results

Case series

Thirty patients with FSIP were included whose general, radiologic-, and disease-related information is reported in Table I. Eighteen patients (60%) underwent EEA, while in 12 (40%) patients a combined EEA-OPF approach was used. Among the latter, 2 patients were initially addressed to EEA, and converted intraoperatively to combined EEA-OPF. An erosion of the posterior wall of the frontal sinus with intracranial invasion was found in four patients: three underwent combined EEA-OPF, while in the other patient the breach was in the lowest part of the wall and addressed endoscopically. None of these cases presented dural invasion or cerebrospinal fluid leak and a dural reconstruction was not needed.

The median follow-up was 37 months (IQR 16-76). Three patients (10%) experienced recurrence, on average 37 months after the previous surgery; two (who received EEA) recurred inside the frontal sinus, while the other patient (treated with the EEA-OPF approach) had a recurrence in the olfactory cleft. These patients underwent a second surgery; one patient with frontal sinus recurrence was managed with a coronal approach, while the others underwent an exclusive endoscopic approach. The patient who received a secondary combined approach recurred after 10 years; the others remained free from disease. There was no significant association between posterior wall shape, lateral frontal sinus extension, intracranial invasion, interorbital distance, or anterior-posterior nasofrontal recess diameter and recurrence of the IP during follow-up. Of note, the two patients who had a recurrence in the frontal sinus during follow-up presented a C-shaped posterior wall of the frontal sinus.

The comparison between endoscopic and combined approaches (EEA-OPF approach) is shown in Table II. No significant difference emerged between the two groups in terms of age, sex, laterality, lateral frontal sinus extension, posterior wall shape, interorbital distance, anterior-posterior nasofrontal recess diameter, follow-up time, or recurrence.

Systematic review

A literature search of PubMed and Scopus databases using the string described retrieved 153 papers on PubMed and 234 on Scopus. Among these, 13 studies respected inclusion criteria 5,8,9,11-21. Including the population in the present study, 195 patients affected by FSIP have been described from 1996 to 2022, with a mean follow-up of 36 months (Tab. III).

Analysing these papers together with the present study, pedicle insertion was found in 94 patients (48.2%, Table III); the posterior wall was the main insertion point in the frontal sinus, followed by the infundibulum and orbital roof.

Considering the 143 surgical procedures explicitly described (71.1%), a classification was proposed dividing them into EEA, a combined approach with osteoplastic flap (EEA-OPF), or an external approach without osteoplastic flap (EEA-EAWO, external trephination, or external fronto-ethmoidectomy techniques). EEA was the most frequent approach performed, followed by EEA-OPF and EEA-EAWO. Thirty-seven (18.9%) patients experienced recurrence, most after EEA-EAWO (Tabs. IV-V).

Discussion

In the last decades, sinonasal IP treatment has evolved from an exclusively open surgery towards complete resection through an exclusive endoscopic transnasal approach 22. Notwithstanding, there are limitations to a purely endoscopic approach to FSIP: due to its challenging localisation, in selected cases, external approaches are advocated for complete tumour resection 23. The present case series selected IP with radiological or intraoperative evidence of insertion point in the frontal sinus and the frontal recess to investigate this aspect, excluding other tumours involving the frontal sinus and frontal recess by extension only. These inclusion criteria were chosen to select a comparable population with a homogeneous risk of recurrence.

Combined EEA-OPF emerged as the technique with the least risk of recurrence, followed by EEA, while combined EEA-EAWO was associated with poor results. Although EEA is tempting for the low rate of related comorbidities 9, combined EEA-OPF has to be considered in some situations. The preoperative choice of the approach should be based on disease-related and anatomical features 9, among which the posterior wall shape might be included. Nonetheless, in some cases of difficult intraoperative management of the tumour, the preoperative indication to EEA might be converted to open surgery with OPF. In two patients of the present case series, the surgical approach was intraoperatively converted due to far lateral extension in the frontal sinus. Both cases had a complex shape of the posterior frontal wall, which might have contributed to reducing the manoeuvring space.

Surgical management of FSIP ranges from an EEA, eventually combined with conservative external approaches (mainly trephination and fronto-ethmoidectomy) or more aggressive procedures (OPF). A coronal approach for OPF is more invasive, and many authors advocate for an exclusive EEA. As far as we know, only one systematic review compared these surgical approaches 10 years ago 23: despite a small population, a low recurrence rate associated with the combined EEA-OPF technique was seen. In the present study, combined EEA-OPF was the most effective technique in the treatment of FSIP: in our case series, no recurrence inside the frontal sinus was seen after a combined EEA-OPF approach, while 2 frontal sinus recurrences occurred in patients who underwent exclusive EEA. In the EEA-OPF group, the only recurrence was in the olfactory cleft, which is an uncommon location and accessible endoscopically. In our systematic review, the available publications support this evidence, with recurrence inside the frontal sinus being more frequent after EEA (15.7%) in comparison with a combined EEA-OPF approach (4.7%). This comparison is not straightforward because of the different indications of the two approaches, as the EEA-OPF approach is usually reserved for more locally extended IP or more complex anatomy. However, it is interesting to compare the outcomes of these two techniques in light of the fact that the combined EEA-OPF approach was the one associated with a lower recurrence rate, despite its more advanced indications. In this optic, according to our data and those described in the literature, the more locally extensive the papilloma, the more aggressive surgical approach is warranted by a good local recurrence rate. Nonetheless, the approach that was mostly associated with frontal sinus recurrence was combined EEA-EAWO (50% recurrence rate), which is probably due to the poor view provided by these techniques. These results suggest that EEA-EAWO should not be the main approach chosen for the management of FSIP.

The literature and the current study aim to identify situations where a combined EEA-OPF approach should be considered. It is worth noting that the present systematic review did not include the transpalpebral craniotomy endoscopic-assisted approach described by Albathi et al. 24. While this approach is interesting, with good potential in the management of inverted papilloma laterally extended in the frontal sinus and hybrid features between EEA-OPF and EEA-EAWO approaches, the choice of excluding it was dictated by the small number of patients described in the literature. Disease-related features should be included in these considerations such as erosion of the anterior wall of the frontal sinus, a breach in the posterior wall with extradural intracranial extension, and histological evidence of squamous cell carcinoma in IP 9. There is a consensus in pedicle-oriented resection for IP 22: if the pedicle is located on the lateral roof of the orbit, anterior wall, upper half of the posterior wall, or diffuse, then EEA might fail to control the disease 9. In this case series, as in our literature review (Tab. IV), the posterior wall of the frontal sinus was the most frequent insertion point 9.

In the present case series, posterior wall shape was evaluated as a novel anatomical parameter, since the posterior wall insertion could be more difficult to address in case of complex configurations. Indeed, a distal vertical component of the wall is difficult to manage endoscopically, considering the curvature of surgical instruments often required to approach the frontal sinus with endoscopic surgery.

Herein, three different configurations are proposed based on the presence of directional components. C and S shapes (characterised by a well-represented distal vertical portion) are considered the most endoscopically challenging, and the patients experiencing recurrence in our population were all characterised by one of these configurations. The management of the posterior wall was also difficult if the anteroposterior diameter of the frontal sinus was insufficient or the interorbital distance was poor. The combination of these three parameters made the approach to the frontal sinus even more challenging, even if it was not statistically associated with an increased risk of recurrence in this case series. As an integration to the algorithm proposed by Pietrobon et al. 9, the combination of these parameters should strengthen the contraindication for an EEA.

Among anatomical features, a lateral extension of the FS cannot be considered an absolute contraindication to exclusive EEA, coherently with the development of a laterally expanded frontal sinus endoscopic approach through orbital transposition, allowing to reach far lateral lesions 25.

Even if in the present study all these parameters could not be independently associated with an increased risk of recurrence (probably due to the small sample), a global evaluation of disease-related and anatomical features should be pivotal in choosing between EEA or a combined EEA-OPF approach. Nowadays, indications are not unique, and the choice of approach depends on many factors, including surgical skills and the experience of the surgical team with each technique, which can lower the risks of complications. The duration of surgery is another important factor to consider in this balance: in some patients, it is not recommended to prolong surgery excessively, for reasons related to general anaesthesia. In relation to the fact that transnasal endoscopic resections can be very long if the anatomy is unfavourable, this may be a factor leading to an open approach, in consideration of the experience of the surgical team. In particular, this article highlights the importance of considering the global anatomical complexity when selecting the surgical approach. The assessment of the posterior wall shape is proposed as part of the balance along with the features proposed by Pietrobon et al. 9, especially when other factors (a small anteroposterior distance and a poor interorbital space) co-participate in challenging the endoscopic posterior wall management. In this balance, the surgical skills and the experience with each technique can be relevant.

The main strength of our study is the substantial number of cases and combined EEA-OPF procedures (compared with the literature). Furthermore, our research benefits from an extensive and prolonged follow-up. Moreover, the systematic review included highly selected studies to focus exclusively on FSIP. However, the retrospective nature of the present study should be noted as its main weakness. Further multicentric and prospective studies are needed to provide a standardised indication to a combined EEA-OPF approach.

Conclusions

FSIP is a challenging disease to treat, which is frequently characterised by difficult surgical management and a higher recurrence rate in comparison with other localisations of IP. Although EEA remains the most widely used technique for its low rate of comorbidities, a combined EEA-OPF approach is useful for complex cases and to prevent recurrence. Lastly, a risk-benefit balance should be considered: a combined EEA-OPF approach should include all disease-related and anatomical features, as well as an assessment of posterior wall shape. Further studies with larger populations and meta-analyses are warranted to reach a standardised indication for a combined EEA-OPF approach.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

PG, AV, BV: made substantial contributions to conception, design and acquisition of data, drafted the article, revised it critically for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved; PH: made substantial contributions to conception of the data, revised it critically for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ethical considerations

Data were collected in respect of local institutional review board recommendations (Comité Ethique et de Protection des Personnes Ile de France IV, Hôpital Saint-Louis-Lariboisière-Fernand Widal, CNIL #2225234). The research was conducted ethically, with all study procedures being performed in accordance with the requirements of the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki.

Written informed consent was obtained from each participant/patient for study participation and data publication.

History

Received: October 8, 2022

Accepted: January 14, 2024

Figures and tables

Figure 1. Radiological classification of posterior wall shape. A) Straight configuration; B) C-shape configuration; C) S-shape configuration. Yellow dotted lines represent the antero-posterior nasofrontal recess distance.

Figure 2. Radiological classification of lateral frontal sinus extension. A) Medial third extension; B) Central third extension; C) Lateral third extension.

| N (% or IQR) | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 19 (64%) |

| Female | 11 (36%) |

| Median age (years) | 57 (46-63) |

| Previous sinonasal surgery | |

| Yes, for previous IP | 11 (36.7%) |

| Yes, for other pathologies | 7 (23.3%) |

| No | 12 (40%) |

| Insertion point | |

| Posterior wall | 5 (16.7%) |

| Infundibulum | 4 (13.3%) |

| Orbital roof | 4 (13.3%) |

| Anterior wall | 3 (10%) |

| Lateral recess | 1 (3.3%) |

| Medial wall | 1 (3.3%) |

| Diffuse insertion in the frontal sinus | 1 (3.3%) |

| Unknown | 11 (36.8%) |

| Lateral frontal sinus extension (in relation to the orbital roof) | |

| Medial third | 4 (13.3%) |

| Central third | 19 (63.4%) |

| Lateral third | 7 (23.4%) |

| Posterior wall shape | |

| Straight | 4 (13.3%) |

| C-shaped | 15 (50%) |

| S-shaped | 7 (23.3%) |

| Unknown | 4 (13.3%) |

| Interorbital distance (median in mm) | 22.2 (20.4-24.9) |

| Anteroposterior recess distance (median in mm) | 8.7 (7.3-11.8) |

| Approach | |

| EEA | 18 (60%) |

| EEA-OPF | 12 (40%) |

| Median follow-up (months) | 37 (16-76) |

| Recurrence | |

| Yes | 3 (10%) |

| No | 27 (90%) |

| Postoperative complications | |

| Yes | 14 (46.7%) |

| Mucoceles | 13 (92.8%) |

| Inflammatory stenosis | 1 (7.2%) |

| No | 15 (50%) |

| Unknown | 1 (3.3%) |

| EEA: endoscopic endonasal approach; OPF: osteoplastic flap; IQR: interquartile range. | |

| EEA | EEA-OPF | |

|---|---|---|

| N (% / IQR) | N (% / IQR) | |

| Number of patients | 18 (60%) | 12 (40%) |

| Median age (years) | 55 (45-62) | 63 (54-78) |

| Previous sinonasal surgery | ||

| Yes, for previous IP | 6 (33.3%) | 5 (41.7%) |

| Yes, for other pathologies | 5 (27.8%) | 2 (16.6%) |

| No | 7 (38.9%) | 5 (41.7%) |

| Insertion point | ||

| Infundibulum | 3 (16.7%) | 1 (8.3%) |

| Posterior wall | 3 (16.7%) | 2 (16.7%) |

| Anterior wall | 2 (11.1%) | 1 (8.3%) |

| Lateral recess | 1 (5.6%) | - |

| Medial wall | 1 (5.6%) | - |

| Orbital roof | 2 (11.1%) | 2 (16.7%) |

| Diffuse insertion in the frontal sinus | 1 (5.6%) | - |

| Unknown | 5 (27.8%) | 6 (50%) |

| Lateral frontal sinus extension (in relation to the orbital roof) | ||

| Medial third | 2 (11.1%) | 2 (16.7%) |

| Central third | 12 (66.7%) | 7 (58.3%) |

| Lateral third | 4 (22.2%) | 3 (25%) |

| Posterior wall shape | ||

| Straight | 2 (11.1%) | 2 (16.7%) |

| C-shaped | 9 (50%) | 6 (50%) |

| S-shaped | 5 (27.7%) | 2 (16.7%) |

| Unknown | 2 (11.1%) | 2 (16.7%) |

| Inter-orbital distance (median in mm) | 22.3 (20.6-25.4) | 21.2 (19-25.1) |

| Anteroposterior recess distance (median in mm) | 8.3 (6.9-11.3) | 10 (7.9-12.6) |

| Follow-up (months) | 32.5 (14-43.7) | 40.5 (17.7-132.7) |

| Recurrence | ||

| Yes | 2 (11.1%) | 1 (8.3%) |

| Inside frontal sinus | 2 (100%) | - |

| Outside frontal sinus | - | 1 (100%) |

| No | 16 (88.9%) | 11 (91.7%) |

| Postoperative complications | ||

| Yes | 6 (33.3%) | 8 (66.7%) |

| Mucoceles | 5 (83.3%) | 8 (100%) |

| Inflammatory stenosis | 1 (16.7%) | - |

| No | 12 (66.7%) | 3 (25%) |

| Unknown | - | 1 (8.3%) |

| EEA: endoscopic endonasal approach; OPF: osteoplastic flap; IQR: interquartile range. | ||

| Year | Author | No. of patients | Pedicle insertion | Surgical approach | Follow-up (mean) | Recurrence (percentage) | Failed surgical approach | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | Chandra et al. 11 | 4 | Not univocal | 1 combined 3 endoscopic | 11 months | 0 | No | |

| 2005 | Dubin et al. 8 | 6 | Not univocal | 1 osteoplastic | 13.5 months | 1 (16.6%) | 1 EEA-OPF | No |

| 4 combined | ||||||||

| 1 endoscopic | ||||||||

| 2007 | Woodworth et al. 12 | 19 | 9 frontal sinus | 5 combined | 40 months | 6 (31.6%) | 4 EEA (inside frontal sinus) | Not univocal |

| 10 frontal recess | 14 endoscopic | 1 EEA (outside frontal sinus) | ||||||

| 1 EEA-EAWO (outside frontal sinus) | ||||||||

| 2008 | Zhang et al. 13 | 9 | 9 nasofrontal recess and infundibulum | 9 endoscopic | 15.1 months | 0 | 0 | |

| 2009 | Yoon et al. 14 | 18 | 1 anterior wall | 11 endoscopic | 36.6 months | 4 (22.2%) | 3 EEA | Not univocal |

| 6 medial wall | 7 combined | 1 EEA-EAWO | ||||||

| 5 diffuse | ||||||||

| 5 posterior wall | ||||||||

| 1 lateral wall | ||||||||

| Sham et al. 15 | 3 | 3 nasofrontal recess | 1 endoscopic | Not specified for subpopulation | 2 (66.6%) | 1 EEA 1 EEA-OPF | Not univocal | |

| 2 combined | ||||||||

| 2010 | Lombardi et al. 16 | 11 | Not univocal | 6 endoscopic | 53.8 months | 2 (18.2%) | 2 EEA | Not univocal |

| 5 combined | ||||||||

| 2015 | Healy et al. 17 | 26 | 9 posterior wall | Not well described (for sure 4 EEA + TREPH) | Not well described | 4 (15.4%) | 4 EEA-EAWO | Not univocal |

| 2 anterior wall | ||||||||

| 1 medial wall | ||||||||

| 1 interfrontal cell | ||||||||

| 11 orbital roof | ||||||||

| 1 supraorbital cell | ||||||||

| 8 not univocal | ||||||||

| 2016 | Adriaensen et al. 18 | 12 | Not univocal | 12 endoscopic | 42 months | 2 (15.4%) | 2 EEA | Not univocal |

| 2017 | Ibrahim et al. 19 | 10 | 2 nasofrontal recess | 5 combined | 24 months | 0 | 1 CSF leak | |

| 3 posterior wall | 5 endoscopic | |||||||

| 5 orbital roof or anterior wall or lateral recess | ||||||||

| 2019 | Pietrobon et al. 9 | 16 | Not univocal | 5 endoscopic | 43 months | 1 (6.3%) | 1 EEA-EAWO | Not univocal |

| 11 combined | ||||||||

| Choi et al. 20 | 23 | Not univocal | Not well described | Not well described | 3 (13%) | 2 EEA 1 EEA-OPF | Not univocal | |

| Sham et al. 21 | 18 | 5 interfrontal septum | 12 endoscopic | 43 months | 9 (50%) | 6 EEA 3 EEA-EAWO | 1 CSF leak | |

| 6 posterior wall | 6 combined | 1 orbital hematoma | ||||||

| 4 infundibulum | 3 stenosis | |||||||

| 3 orbital roof | ||||||||

| EEA: endoscopic endonasal approach; EAWO: external approach without osteoplastic flap; OPF: osteoplastic flap; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; TREPH: trephination. | ||||||||

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Insertion point | |

| Described (%) | 94 (48.2%) |

| Posterior wall | 28 (29.8%) |

| Infundibulum | 19 (20.2%) |

| Orbital roof | 19 (20.2%) |

| Medial wall | 14 (14.9%) |

| Anterior wall | 6 (6.4%) |

| Diffuse insertion in the frontal sinus | 6 (6.4%) |

| Lateral recess | 2 (2.1%) |

| Not univocal | 101 (51.8%) |

| Approach | |

| Described (%) | 143 (73.3%) |

| EEA | 83 (58%) |

| Combined | 59 (41.3%) |

| EAWO | 16 (27.1%) |

| OPF | 43 (72.9%) |

| Exclusive external approach | 1 (0.7%) |

| Not univocal | 52 (26.7%) |

| Mean follow-up (months) | 36 |

| Recurrence | |

| Yes | 37 (18.9%) |

| Inside frontal sinus | 23 (62.2%) |

| Outside frontal sinus | 9 (24.3%) |

| Not univocal | 5 (13.5%) |

| No | 158 (81.1%) |

| EEA: endoscopic endonasal approach; EAWO: external approach without osteoplastic flap; OPF: osteoplastic flap. | |

| EEA | EEA + EAWO | EEA + OPF | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (83 patients) | (16 patients) | (43 patients) | |

| Recurrence inside frontal sinus | 13 (15.7%) | 8 (50%) | 2 (4.7%) |

| Recurrence outside frontal sinus | 6 (7.2%) | 2 (12.5%) | 1 (2.3%) |

| Not univocal recurrence site | 3 (3.6%) | 1 (6.2%) | 1 (2.3%) |

| Total | 22 (26.5%) | 11 (68.7%) | 4 (9.3%) |

| EEA: endoscopic endonasal approach; EAWO: external approach without the osteoplastic flap; OPF: osteoplastic flap. | |||

References

- Lisan Q, Laccourreye O, Bonfils P. Sinonasal inverted papilloma: from diagnosis to treatment. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2016;133:337-341. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ANORL.2016.03.006

- Kamel R, Khaled A, Abdelfattah A. Surgical treatment of sinonasal inverted papilloma. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;30:26-32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MOO.0000000000000781

- Russo C, Elefante A, Romano A. A multimodal diagnostic approach to inverted papilloma: proposal of a novel diagnostic flow-chart. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2021;50:499-504. doi:https://doi.org/10.1067/J.CPRADIOL.2020.04.009

- Lee J, Roland L, Licata J. Morphologic, intraoperative, and histologic risk factors for sinonasal inverted papilloma recurrence. Laryngoscope. 2020;130:590-596. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.28078

- Shohet J, Duncavage J. Management of the frontal sinus with inverted papilloma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;114:649-652. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0194-5998(96)70263-2

- Adriaensen G, van der Hout M, Reinartz S. Endoscopic treatment of inverted papilloma attached in the frontal sinus/recess. Rhinology. 2015;53:317-324. doi:https://doi.org/10.4193/Rhino14.177

- Goudakos J, Blioskas S, Nikolaou A. Endoscopic resection of sinonasal inverted papillomas: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2018;32:167-174. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1945892418765004

- Dubin M, Sonnenburg R, Melroy C. Staged endoscopic and combined open/endoscopic approach in the management of inverted papilloma of the frontal sinus. Am J Rhinol. 2005;19:442-445. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/194589240501900504

- Pietrobon G, Karligkiotis A, Turri-Zanoni M. Surgical management of inverted papilloma involving the frontal sinus: a practical algorithm for treatment planning. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2019;39:28-39. doi:https://doi.org/10.14639/0392-100X-2313

- Özdemir M, Kavak R, Öcal B. A novel anatomical classification of the frontal sinus: can it be useful in clinical approach to frontal sinusitis?. Egypt J Otolaryngol. 2021;37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/S43163-021-00099-5

- Chandra R, Schlosser R, Kennedy D. Use of the 70-degree diamond burr in the management of complicated frontal sinus disease. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:188-192. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00005537-200402000-00002

- Woodworth B, Bhargave G, Palmer J. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic and endoscopic-assisted resection of inverted papillomas: a 15-year experience. Am J Rhinol. 2007;21:591-600. doi:https://doi.org/10.2500/ajr.2007.21.3086

- Zhang L, Han D, Wang C. Endoscopic management of the inverted papilloma with attachment to the frontal sinus drainage pathway. Acta Otolaryngol. 2008;128:561-568. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00016480701635191

- Yoon N, Batra P, Citardi M. Frontal sinus inverted papilloma: surgical strategy based on the site of attachment. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2009;23:337-341. doi:https://doi.org/10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3328

- Sham C, Woo J, van Hasselt C. Treatment results of sinonasal inverted papilloma: an 18-year study. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2009;23:203-211. doi:https://doi.org/10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3296

- Lombardi D, Tomenzoli D, Buttà L. Limitations and complications of endoscopic surgery for treatment for sinonasal inverted papilloma: a reassessment after 212 cases. Head Neck. 2011;33:1154-1161. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/HED.21589

- Healy D, Chhabra N, Metson R. Surgical risk factors for recurrence of inverted papilloma. Laryngoscope. 2016;126:796-801. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/LARY.25663

- Adriaensen G, Lim K, Georgalas C. Challenges in the management of inverted papilloma: a review of 72 revision cases. Laryngoscope. 2016;126:322-328. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/LARY.25522

- Ibrahim A, Morsi H, Hassab M. Surgical strategy for frontal sinus inverted papilloma. Egypt J Ear Nose, Throat Allied Sci. 2017;18:241-246. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EJENTA.2017.11.001

- Choi W, Lee B, Kim J. Long-term outcome following resection of sinonasal inverted papillomas: a single surgeon’s experience in 127 patients. Clin Otolaryngol. 2019;44:652-655. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/COA.13325

- Sham C, van Hasselt C, Chow S. Frontal inverted papillomas: a 25-year study. Laryngoscope. 2020;130:1622-1628. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/LARY.28245

- Pagella F, Pusateri A, . Evolution in the treatment of sinonasal inverted papilloma: pedicle-oriented endoscopic surgery. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2014;28:75-81. doi:https://doi.org/10.2500/AJRA.2014.28.3985

- Walgama E, Ahn C, Batra P. Surgical management of frontal sinus inverted papilloma: a systematic review. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:1205-1209. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/LARY.23275

- Albathi M, Ramanathan M, Lane A. Combined endonasal and eyelid approach for management of extensive frontal sinus inverting papilloma. Laryngoscope. 2018;128:3-9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26552

- Karligkiotis A, Pistochini A, Turri-Zanoni M. Endoscopic endonasal orbital transposition to expand the frontal sinus approaches. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2015;29:449-456. doi:https://doi.org/10.2500/AJRA.2015.29.4230

Downloads

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright

Copyright (c) 2024 Società Italiana di Otorinolaringoiatria e chirurgia cervico facciale

How to Cite

- Abstract viewed - 312 times

- PDF downloaded - 112 times

PDF

PDF