Otology

Vol. 45: Issue 1 - February 2025

Complications in 2000 adult and paediatric cochlear implants: what to expect and when

Abstract

Objective. To identify the incidence of intra- and postoperative complications of adult and paediatric cochlear implants (CIs) in a large cohort with long follow-up.

Methods. Retrospective chart analysis of 2000 consecutive cases of CI in a single institution.

Results. 8.9% of paediatric CIs developed a complication after a mean period of 5.5 ± 5.8 years. 12% of adult CIs developed a complication after a mean period of 3.5 ± 5.3 years. Seroma was the most frequent paediatric complication (1.8%), after a mean of 8.9 ± 5.4 years, while vertigo was the most common complaint in adults (2.5%), emerging in the first year. Both complications were generally managed conservatively. Acute otitis media or abscess with extrusion of the receiver/stimulator required surgical revision, with or without CI explantation, in 23.5% and 76.9% of cases, respectively. Cholesteatoma or chronic otitis media were always treated surgically and required CI explantation in 86.7% of cases. All cases complicated by device failure (1.2% and 0.8% of paediatric and adult CIs, respectively) were treated with CI explantation and reimplantation, and emerged after a mean of 5 ± 4 years.

Conclusions. Knowledge and decades long monitoring of the complications related to CIs are fundamental.

Introduction

Cochlear implantation is considered a safe and life-changing procedure with relatively low rates of complication 1. The increasing numbers of sequential and simultaneous bilateral cochlear implantations 2, the lowered minimum age at implantation 3, the progressive expansion of indications to a cochlear implant (CI), and the widespread implementation of CIs around the world 4, will undoubtedly be associated with an increased incidence of complications. Subsequently, an increased need of occasional reimplantation will also follow.

The World Report on Hearing estimates an annual risk of 0.4% of device failure 5. Additionally, approximately 7.6% of cochlear implantations are expected to undergo revision surgery 6 and 5.5% of CIs will be explanted and reimplanted 7. A Manufacturer And User facility Device Experience database study conducted from the 1st of January 2010 to the 31st of December 2020 showed that the total complication rate of infection, extrusion, facial nerve stimulation and cerebrospinal fluid leak (CSF) was 5.9% 8, similarly, the French Cochlear Implant Registry study highlighted 5.6% of complications in CIs from January 2016 to December 2016, including multiple complications among which cochleovestibular dysfunction and haematoma 9.

The objective of this study was to retrospectively collect information on the complications affecting a tertiary institution cohort of both adult and paediatric CI cases, in order to identify the actual prevalence and incidence of CI complications and properly counsel patients and caregivers about what to expect and when.

Materials and methods

A retrospective analysis of the clinical charts of 2000 consecutive cochlear implantations at a single tertiary institution, between June 1991 and December 2022, was performed. Patients undergoing cochlear implantation but lost to follow-up after activation were excluded from the analysis. Patients were included but considered lost to follow-up if activated and initially followed at our centre, but skipped at least two evaluations. Only data referring to the period that they were followed at our centre was considered. Patients operated on elsewhere but followed by our institution were also excluded from the analysis.

All surgeries were performed by two surgeons. The surgical technique in most cases consisted of a simple mastoidectomy with a transmastoid posterior tympanotomy, allowing access to the promontory. A subtotal petrosectomy was performed in cases with chronic otitis media with or without cholesteatoma. No anatomical variations in the middle ear required a subtotal petrosectomy. When access to the round window was not feasible, a cochleostomy was performed anteriorly and superiorly to the round window. Modifications of the procedure mostly affected the retroauricular skin incision (its length was reduced over time). Since 2016, in line with the growing experience in revision surgery, bone dust to secure the electrode and obliterate the posterior tympanotomy has been abandoned. Since 2021, the posterior external auditory canal is reinforced by bone dust and extensive thinning is avoided when possible. Intraoperative facial nerve monitoring was conducted since 1999 (Medtronic NIM® Nerve Monitoring System). The intraoperative evaluation of CI function, with assessment of impedance levels and neural response telemetry (NRT), was performed in all patients, either automatically or manually. An X-ray was performed intraoperatively in paediatric cases and postoperatively in adult cases to confirm intracochlear electrode positioning.

Antibiotic prophylaxis was administered to all patients, intraoperatively (cefazoline 50 mg/kg) and for 5 postoperative days, except allergic patients or infected cases with the availability of an antibiogram. The first fitting and activation was programmed after 6 days from surgery and a maximum use of the CI (also during sleep) was suggested.

A comparison between different devices goes beyond the scope of this study and will therefore be ignored.

Follow-up consisted in evaluation by an inhouse team of surgeon, hearing aid specialist and speech therapist. Children were also evaluated by an inhouse pedagogist.

The time of occurrence of each complication was recorded and analysed. Complications were considered as either intra- or postoperative. Each complication was classified as ‘‘minor’’ when it required conservative management and had no permanent effects, whereas ‘‘major’’ complications required hospitalisation or surgical revision, or had permanent consequences. The number of complications in each patient and each CI were also evaluated, as well as recurrences of the same complication over time. Finally, complications were analysed by comparing the adult and paediatric populations, by the age at occurrence, and by the time lag between CI surgery and complication.

A literature review of articles with at least 100 patients or CIs was conducted. Articles published before the year 2000 were excluded. Articles referring to a single complication or specific populations were excluded, unless the population referred to was limited to “paediatric” or “adult”, which were included but specified. Moreover, articles excluding device related complications (e.g. device failure) were included and specified.

Statistical analysis and graphs were performed using Graphpad Prism software (GraphPad Software 9.0, Inc, San Diego, CA, USA). Data were analysed using descriptive statistics; continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD); categorical variables were expressed as percentage (frequency). Fisher’s exact test and Mann-Whitney test were used when comparing populations. Log-rank test was used to compare time to complication from surgery between the groups. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Results

In all, 2000 CIs were analysed in 1329 patients. Of these CIs, 1963 were primary surgeries and 37 were reimplantations. One hundred and sixteen patients were lost to follow-up (158 CIs) after a mean of 6.9 ± 5.5 years.

Paediatric population

Eight hundred and forty-two paediatric patients underwent 1419 CIs. Four hundred and three children underwent bilateral simultaneous CI, while 174 underwent bilateral sequential CI. Among them 20 patients had undergone the first CI in another centre (for this reason complications will only consider the ear operated upon in our centre) and 8 received their second implant when adults. Four patients received a sequential CI simultaneously to a contralateral CI explant, namely “monaural sequential”.

The mean age at the time of implantation was 4.1 ± 3.9 years (range, 8 months - 17.9 years). The mean duration of follow-up was 11.6 ± 5.8 years (range, 4 months - 27.7 years).

One hundred and twenty-six CIs developed a complication in 108 ears (91 patients). Nineteen CIs developed recurrent complications. Overall, 8.9% of paediatric CIs were complicated after a mean period of 5.5 ± 5.8 years (range, intraoperative - 23.4 years after CI).

Adult population

Five hundred and eighty-one CIs were implanted in 487 adult patients. Thirty-three adults underwent bilateral simultaneous CI, while 51 patients underwent bilateral sequential CI. Twelve bilateral CI patients had undergone the first CI in another centre and, as previously stated, 8 received their first implant at our centre when children. One patient received a sequential CI concurrently with a contralateral CI explant (monaural sequential). Thirteen CIs were revision surgeries, of which 3 were revisions of paediatric CIs. Revision of CIs implanted elsewhere were excluded.

The mean age at implantation was 45.6 ± 16.5 years (range, 18-83.3 years). The mean duration of follow-up was 12.9 ± 7.3 years (range, 4 months - 31.6 years).

Seventy CIs developed a complication in 61 ears in 59 patients. Four CIs developed a recurrent complication. Overall, 12% of adults presented a complication after a mean period of 3.5 ± 5.3 years (range, intraoperative - 21.7 years after CI).

Complications

Complications were subgrouped, according to time of occurrence, into intraoperative (which also included immediate postoperative complications emerging in the operating room) and postoperative. Some events were included as complications although they could be independent of cochlear implantation or even surgery, because they could theoretically result from the presence of the CI which could act as a trigger of inflammatory response, as well as the fact that the presence of a CI demands more prompt and definite management of the “complication”.

Intraoperative complications consisted in: array misplacement, gusher, vestibular, chorda tympani or facial nerve injury. No intraoperative jugular bulb or sigmoid sinus injuries occurred, and there were no cases of CSF leak or dural tears.

Two paediatric arrays were misplaced in the vestibule; both were revised after radiologic confirmation. Five adult patients had an array misplacement: one had a vestibular insertion and was revised; 4 had a tip fold-over, which was revised only in 2 patients; the other 2 patients showed good audiologic results at activation and were therefore only mapped accordingly.

Gusher complicated 9 paediatric surgeries. Two patients had bilateral simultaneous CI and presented bilateral gusher. Three patients had unilateral CI. Two patients had bilateral sequential CI, one presented gusher in only one surgery, whereas the other had bilateral gusher but had undergone the first CI elsewhere (the latter CI being done elsewhere was excluded and was not considered in the reported 9 surgeries with gusher). Seven of 9 ears (77.8%) were associated with inner ear malformations identified on preoperative radiologic evaluation. No adult surgery presented gusher.

Three adult patients had evident postoperative acute vestibulopathy with self-limiting vertigo that procrastinated hospital discharge.

One adult patient had an intraoperative chorda tympani injury with postoperative dysgeusia that lasted for 2 months. No treatment was indicated. Although no other patient complained of dysgeusia, we expect this complication to be greater than reported.

Facial palsy complicated 2 paediatric patients and one adult patient. The first paediatric case was a revision surgery with CI explantation and reimplantation after device failure and presented a complete grade VI acc. to House-Brackmann (HB) facial palsy 10. The child was treated with speech therapy with partial improvement. The other child had a right HB grade III facial paresis and bilateral gusher in an enlarged vestibular aqueduct syndrome. The facial paresis improved over time into a HB grade II. The adult case presented a transient postoperative facial palsy with subsequent complete recovery.

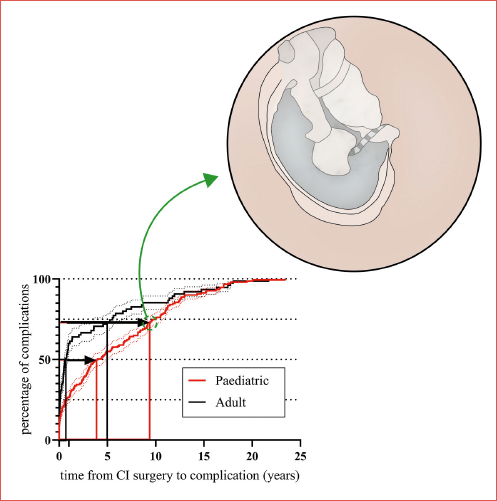

The time of occurrence/diagnosis of each postoperative complication is presented in Figure 1, showing that some complications tend to occur earlier and closer to surgery, whereas others are delayed or spread over time.

Magnet dislocation was not included since this occurrence was strictly associated with MRI; it complicated 3 paediatric and 4 adult patients. A patient with vestibular schwannoma had recurrent magnetic dislocations after serial MRIs.

Seroma was the most frequent complication in children, affecting 1.8% of all paediatric CIs (26 CIs) after a mean of 107 ± 65.2 months. Six cases recurred, one of which had multiple recurrences. Patients developing bilateral seroma had also statistically more recurrences (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.02). Children presented seroma at a median age of 12 years (mean 10.6 ± 6.4). Although female patients presented seroma at a younger age, median 7.7 vs 12.7 years of age in girls and boys, respectively, the difference was not statistically significant (Mann Whitney test, p = 0.12). The presence of seroma deters magnetic attraction and dampens radio-frequency transmission to the internal receiver/stimulator (R/S). Three seromas concurred with ipsilateral acute otitis media. One seroma evolved into skin flap dehiscence and R/S extrusion, whereas another seroma was followed by device failure. Most cases (17/26) were treated as outpatients with anti-oedema ointment plus compressive dressing and by oral antibiotics and corticosteroids. Occasionally, an oral antihistaminic was added. Nine patients received only oral treatment (without dressing), and 2 resolved without treatment. Four patients were hospitalised for intravenous therapy and compressive dressing. Finally, 2 patients underwent surgical revision after failure of conservative treatment. Seroma affected 0.8% of adult patients (5 CIs), without recurrent or bilateral cases, after 34.1 ± 37.3 months. One case evolved in R/S migration. All adult patients were treated with oral antibiotics and corticosteroids. Overall, 9.6% of seromas evolved into more serious complications. Although seromas mainly affected the paediatric population, there was no statistically significant difference between the occurrence of seroma in the two populations (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.1607). Moreover, the complication affected equally females and males. Seromas occurred in significantly older children compared to acute otitis media (Mann Whitney test, p = 0.0027), and at similar ages in children affected by chronic otitis media (Mann Whitney test, p = 0.8048); seroma occurrence was also delayed, albeit not statistically significant, in children affected by extrusion (Mann Whitney test, p = 0.0645). Acute otitis media (AOM) with either ear discharge or mastoiditis occurred in 16 paediatric CIs (1.1%), with 4 recurrences (25%). Simple AOM were not taken into account when not associated to ear discharge or mastoiditis. The infection developed after a mean of 13.1 ± 15.9 months after CI surgery, (range, 20 days - 52 months). The complication predominantly affected younger children, median 4 (mean age 5.1 ± 4.3 years old). Seven patients were treated successfully with oral antibiotics, whereas 9 were hospitalised and treated with intravenous antibiotics. Four patients were treated surgically: one had a surgical evacuation of mastoid cavity infection, whereas 3 patients were non-responsive to antibiotics and had CI explantation, with simultaneous reimplantation in one case due to apparent macroscopic disease eradication and washing of the cavity with antibiotics which were also administered intravenously. Only one adult developed AOM with ear discharge after more than 6 years from surgery; he recovered with oral antibiotics. AOM with either ear discharge or mastoiditis affected significantly more paediatric CI cases than adult cases (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.0326).

Cholesteatoma or chronic otitis media (COM) with exposure of the electrode array complicated 13 paediatric CIs in 9 patients. Two patients with bilateral CI developed bilateral cholesteatoma, while 2 additional patients with bilateral CI developed cholesteatoma on one side and COM with tympanic perforation on the other side. Two cases had previously recurrent AOM. Cholesteatoma or exposure of the electrode array through perforation of the tympanic membrane was diagnosed after a mean of 5.7 ± 4.7 years from CI surgery. The mean age at presentation was 12 ± 6.2 years (median 10 years). All patients underwent revision surgery. In 2 cases the disease was eradicated with CI preservation because not affected by the disease. Eleven cases required CI explantation and conversion to subtotal petrosectomy. In one patient, the electrode, which was left in the cochlea in order to preserve cochlear patency, caused meningitis with recurring headache and fever that was partially responsive to ciprofloxacin. The case resolved after the removal of the electrode (positive for Pseudomonas aeruginosa) and its replacement with a gauge; the patient was reimplanted after 3 months of appropriate antibiotic therapy. A new CI was reimplanted (ipsilaterally or contralaterally) in 6 cases. Two adult patients developed cholesteatoma which was diagnosed after 11.2 and 21.6 years from CI surgery. The latter had Cogan’s syndrome and simultaneously developed transitory facial palsy and cholesteatoma; moreover, he had an ossified contralateral cochlea. Both cases were explanted and reimplanted simultaneously. Although there was no significant difference in the incidence of cholesteatoma or COM between the two populations (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.2559), the complication was diagnosed significantly earlier in paediatric cases (unpaired t test, p = 0.0142).

Abscess with R/S extrusion complicated 0.8% of paediatric patients (12 CIs) after a mean of 2.9 ± 4.7 years (range, 18 days - 16.6 years). One case recurred after 2 months of apparent resolution. The complication affected mostly young children (median age 3.2 years, mean age 6.2 ± 5.9 years). Two cases resolved with wound dressing and intravenous antibiotics, whereas 10 cases were surgically revised. Three cases had a surgical toilette and the R/S was covered by a skin flap, while 7 were explanted. In 3 cases the infected area was completely removed and a simultaneous new CI was implanted covered by healthy tissue. One adult case was complicated with R/S extrusion, which was managed with wound dressing.

R/S migration occurred in 3 paediatric patients (0.2%) after 4.9 ± 1.4 years, and 5 adult cases (0.8%) after 7 ± 7.3 years from CI surgery. R/S migration complicated a previous seroma in one child. No treatment was necessary in 4 cases, however in one paediatric and 3 adult patients a surgical revision with explantation and reimplantation was indicated, owing to skin flap necrosis with R/S exposure.

Device failure was the main cause of CI explantation in both populations (Fig. 2). Seventeen (1.2%) paediatric cases presented device failure after 4.2 ± 3.6 years from CI surgery, 2 after head trauma, and 5 (0.8%) adult cases after 7.6 ± 4.5 years. All cases were confirmed by the manufacturers’ specialist and were treated with CI explantation and simultaneous reimplantation. There was no statistically significant difference between the incidence of device failure (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.6405) or time to complication (unpaired t test, p = 0.0885) between the two populations. Furthermore, 7 paediatric cases presented a characteristic decrement without evolving in device failure after 10.1 ± 4.4 years from CI. Curiously, all cases were in girls. Only one case was surgically treated with CI explantation and reimplantation for insufficient auditory benefit with subsequent improvement of performance 11.

Vertigo was the most common complaint in adults, affecting 15 cases (2.5%) with 2 recurrences. It was significantly more common in adults than children (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.0001). Vertigo emerged immediately after surgery in one case, prolonging hospitalisation, and 2 patients suffered from vertigo in the first month after CI. Vertigo occurred mostly in the first year (mean 11.1 ± 14.8 months), except in 2 patients (after more than 3.5 years). Patients complaining of vertigo were mostly middle aged (mean 54.5 ± 13.2, median 53.6 years) and significantly older than the adult CI population (mean 45.5 ± 16.5, median 44.8 years, Mann Whitney test p = 0.0359). There was no significant difference in vertigo between female and male patients (Mann Whitney test p = 0.4136). Four cases were caused by benign positional paroxysmal vertigo and one by endolymphatic hydrops, whereas the rest were associated with vestibular hypo- or areflexia. All patients except one were successfully treated as outpatients with oral betahistine and/or vestibular rehabilitation therapy. Two children suffered from vertigo at 8.1 and 9.5 years after CI surgery, and were both bilateral CI users. In one case vertigo developed after CSF leak in an inner ear malformation (enlarged vestibular aqueduct and incomplete partition type II). The CSF leak occurred after almost 6 years after CI surgery.

Six adult patients complained persistence of tinnitus after CI (1%). There were no new cases of tinnitus after CI. Five cases resolved after CI mapping or oral steroids, whereas one suffered from invalidating low frequency tinnitus and was admitted in order to receive intravenous steroids with subjective benefit. No child complained of tinnitus.

Facial nerve (FN) stimulation complicated 10 paediatric CIs with 5 recurrences and 6 adult CIs with one recurrence. FN stimulation by the CI, in children, occurred after a mean 6.6 ± 6.1 years (range, 4.2 months - 12.4 years) from CI positioning with a recurrence after a mean 3.9 ± 2.6 years after the first FN stimulation. In the adult population, FN stimulation occurred after 3.9 ± 5.6 years (range, 20 days - 12.9 years) which recurred in one case after 5 years. Although this complication emerged earlier in adults, there was no statistically significant difference with paediatric patients (unpaired t test, p = 0.4302). All cases were treated by modifications of the CI maps, with change in pulse width or exclusion of contacts, especially those located at the upper basal turn, closer to the facial nerve canal. Not all cases had an evident cause, although otosclerotic patients were the most affected.

Minor complications required conservative management, while most major complications urged hospitalisation, surgical revision, or CI explantation with or without reimplantation. The percentages of each treatment of all complications is depicted in Figure 3.

Patients who developed infectious complications were significantly younger than those who developed chronic inflammatory complications (AOM and abscess vs. seroma and COM; Mann Whitney p < 0.0001). The time from surgery to complication was significantly different between children and adults (Cover figure).

There were no statistically significant differences between male or female patients considering the incidence of complication or age at occurrence.

Table I summarises the articles with at least 100 patients or CIs since the year 2000 12-48.

Discussion

Parallel to the increase in patients with CI, based on the large amount of evidence on the benefit of hearing restoration by such a device, complications secondary to CI are also expected to increase over time.

Most complications arise in the first year after surgery; as depicted in Cover figure, the timing in which complications occur is very different between the adult and paediatric populations. Half of adult complications occur in the first year after implantation and another 25% within the next 5 years; on the other hand, in the paediatric population, complications are equally distributed between the first 4 years and the following decade. CI surgery can have serious complications even after a long period of time, and therefore correct counseling must be carried out by stressing the necessity of long-term follow-up. Although our centre also sees patients from distant regions (national and international), the presence in the same centre of all the specialists necessary for the development of communication skills of deaf patients encourages patients to maintain long follow-ups at our centre. This allowed us to identify many complications that only emerge after many years. Unfortunately, 8.7% of patients who were lost to follow-up, after a mean of 6.9 ± 5.5 years, might have developed complications. This could have been avoided with a national/international registry.

Nowadays, CI is often inserted in patients at a few months of age with a very long life expectancy. Thus, the analysis of the trend of complications over time is of crucial importance for at least two reasons: 1) to understand the causes of their onset and therefore for development of preventive strategies; 2) for adequate counselling in the context of informed consent.

In our study, the overall rate of complications in 2000 surgeries was 9.8% after a mean overall follow-up of 11.6 ± 5.9 years (median 12.1; range, 4 months - 31.6 years). A longer follow-up time is likely to more precisely identify the prevalence of complications over time.

Figure 3 shows how complications were treated at our centre: most were minor events that were successfully managed conservatively without the need for revision surgery, in agreement with the literature 25,49. An accurate preoperative radiological study of every case is mandatory before undertaking any CI surgery, to plan the correct surgical approach and avoid, when possible, intra- and postoperative complications, while preoperative radiology might help predict possible or inevitable complications, such as gusher in specific malformations. Inner ear malformations may increase the incidence of cerebrospinal fluid gusher 50. In our experience, 77.8% of cases of gusher occurred in inner ear malformations (enlarged vestibular aqueduct, incomplete partition [IP]-II, IP-III, Mondini dysplasia). Most studies report a 40-50% incidence among various anatomical malformations 51. In particular, common cavity malformation, Mondini dyplasia, and enlarged vestibular acqueduct present a bony defect of the internal auditory meatus fundus leading to gusher 52,53. A recent review on 40 studies, shows an overall rate of gusher of 48.5% in case of enlarged vestibular aqueduct with IP-II cases, compared to 27.7% in enlarged vestibular aqueduct alone 54. On the other hand, all IP-III malformations present gusher due to a direct communication between the cochlea and internal auditory canal 55.

Intraoperative radiology is indicated, especially in children, in order to reveal complications that must be immediately corrected, such as array misplacement. A case series and review in 2022, addressed 37 array misplacements out of 7,053 procedures (0.5%) in 39 different articles, demonstrating that this complication is very rare. The vestibular system is the region most frequently involved (50.8%) and the main cause described is difficulty in anatomical visualisation. Unfortunately, intraoperative imaging was reported in only 10 cases (16.4%) 56. Other misplaced cases are, in fact, diagnosed only after persistent vestibular symptoms, anomalous telemetry, or suspicion by the surgeon 57-59. Our overall rate of misplacement was 0.3%.

A systematic review in 2018 about the effect of chorda tympani injury during non-inflammatory middle ear surgery found that more patients with a stretched chorda tympani report hypogeusia, ageusia or altered taste sensation than patients with a sacrificed chorda tympani 60. Despite this, there is no consensus whether sacrificing or stretching is associated with fewer symptoms 61.

Facial nerve injury in otologic procedures occurs in around 17% of cases 62. A systematic review of iatrogenic nerve facial palsy published in 2023 comprised two retrospective studies of CI surgery with nerve monitoring 63, as we also perform; in these studies, facial palsy was uncommon, with an incidence ranging from 0.6% to 0.7% in cases with intraoperative facial nerve monitoring versus 0.7% in cases without intraoperative facial nerve monitoring 64,65.

The causes of facial nerve palsy in CI surgery are direct injury to the facial nerve during the operation, indirect injury due to chorda tympani nerve injury, thermal injury due to drilling, reactivation of herpes virus, or oedema and thrombus of the facial nerve due to bacterial infection 66.

Facial nerve weakness can be a minor and temporary complication secondary to oedema or herpes virus reactivation 67 with complete recovery over time following therapy. In our experience, palsy without complete healing is the consequence of major direct injury during surgery due to non-standard procedures in complicated revisions or inner ear malformations.

Seroma was the most frequent complication in children (1.8%), with a late onset (after a mean of 8.9 ± 5.4 years), while vertigo was the most common complaint in adults (2.5%). The latter generally emerged in the first year after surgery (mean 11.1 ± 14.8 months), and was predominantly related to vestibular hypo- or areflexia. Both complications were generally managed conservatively. The causes of seroma are unclear and recurrent swelling after CI is not extensively studied in the literature, although possible factors in its development are minor head trauma near the R/S, subacute infection related to biofilm, or an allergic reaction to the silicone coating of the CI. A recent study recommends a conservative approach with avoidance of aspiration, as these cases will usually recover without adverse outcomes 68. We approached this complication with conservative therapy in most cases (65.3%), and more aggressively in refractory cases.

Vertigo after CI can have different triggers, such as labyrinthine trauma manifesting as peripheral vestibulopathy, iatrogenic perilymphatic fistula, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, or mechanical or physiological cochlear damage (from systemic inflammatory processes) resulting in secondary endolymphatic hydrops 69, and even the electrical stimulation from the CI has been implicated 70.

Infectious complications such as AOM and abscess along the R/S with extrusion of the latter required surgical revision, with or without CI explantation, in 23.5% and 76.9% of cases, respectively. Children were significantly more affected in accordance with the literature 71-73. A possible cause of recurrent AOM is adenotonsillar hypertrophy, which can occur at a very young age after the CI surgery and can play a key role in recurrent infections of the upper airway with involvement of the middle ear. Revision surgery, with or without explantation, in AOM was only performed on children after failure of more conservative treatments. If R/S migration is complicated by skin flap necrosis or dehiscence with exposure of the R/S and not responsive to conservative treatments, explantation is strongly recommended 74. Most infectious cases have an optimal response to antibiotics, although in some cases tend to recur as soon as the treatment is suspended. We suspect these resistant cases depend on pathogenic bacterial biofilm on the CI (although bacteria culture tests of the explant were rarely positive). When the surrounding tissue is macroscopically healthy, and accurate toilette has been achieved, a simultaneous reimplantation can be attempted. In order to prevent infectious complications, we prescribe a full course of antibiotic therapy which begins with intravenous intraoperative antibiotics and continues after discharge at home with oral antibiotics, even if postoperative treatment do not lower the risk of infection or reinterventions during follow-up 74. Unfortunately, no strategies have been identified that prevent wound infection after CI 74.

Cholesteatoma or COM, which was diagnosed after a mean of 5.7 ± 4.7 years after CI surgery in children and after 11.2 and 21.6 years in adults, was always treated surgically and required CI explantation in 86.7% of cases. The possible causes of COM, with or without cholesteatoma, after CI, are persistent middle ear pathology, refractory effusion, tympanic atelectasis, recurrent otitis media, and foreign body mucosa reaction, but also inadvertent fenestration of the posterior canal wall during drilling 75. We now reinforce the posterior external auditory canal with bone patè to prevent atelectasis and/or COM, and perform preventive subtotal petrosectomy in adults with signs of dysventilation or refractory effusion. The ideal treatment of COM and cholesteatoma after CI comprises a subtotal petrosectomy 75. If indicated and feasible, simultaneous or subsequent device re-placement should be performed with accurate fixation in order to prevent device migration 76. This could suggest that improving the surgical technique and experience may reduce the risk of complications, even if we have not observed significant differences between the beginning and end of the career of the two surgeons. Despite the obvious increase in surgical experience, this could support the hypothesis that some complications are nearly inevitable.

Finally, all cases complicated by device failure were treated with CI explantation and reimplantation, which was the main cause of CI explantation in both populations (Fig. 2). This complication emerged after a mean of 5 ± 4 years (range, 2.3 months - 14.7 years). In our experience, only 2 patients had previous head trauma, and the other cases were not attributable to a specific cause other than malfunction of the CI. This complication was the main cause of explantation and reimplantation, in accordance with the literature, especially in children 77-79. The explanted device must be registered at the Ministry of Health which will send it to the company who will examine the device to identify possible causes of the failure. Figure 2 depicts the causes of CI explantation, which is the most extreme measure, and is only used when utterly necessary.

A complication that can be solved without surgery, but with an appropriate fitting, is facial nerve stimulation. The causes of this complication can depend upon the close proximity of the facial nerve to the outer wall of the cochlea, need to increase electric currents to stimulate the auditory nerve after long deprivations, impedance decrease and current leakage in temporal bone fractures, otosclerosis, or meningitis. The permanent presence of a hearing aid specialist in the audiological centre is recommended for fitting and follow-up, especially in these particular cases 80.

Conclusions

CI surgery remains a safe procedure that is routinely performed worldwide. Knowledge and decades long monitoring of complications related to this procedure are fundamental, as it involves the placement of a foreign body, the CI, in patients who are destined to be lifelong users, acting as a trigger for processes that are still unexplored. Although complications affect up to 8.9% of paediatric CIs and 12% of adult CIs, the benefits of this procedure outweigh the risks for most recipients and their families when correctly counselled.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

The Fondazione Audiologica di Varese funded the cost of publication for this article.

Author contributions

EC: designed the study; VS, FDM: collected the data, wrote the manuscript; VS: analyzed and interpreted the data; ES, EC: edited the manuscript.

Ethical consideration

This is a retrospective study on patients’ records, the research was conducted ethically after authorization by the institutional review board (0034386), with all study procedures being performed in accordance with the requirements of the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki.

History

Received: October 16, 2023

Accepted: October 9, 2024

Figures and tables

Figure 1. Postoperative complications of cochlear implants (CI) in children and adults and time of occurrence in years after CI surgery. Each point is a single complication. AOM: acute otitis media; COM: chronic otitis media; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; R/S: receiver/stimulator.

Figure 2. Percentage of each type of complications treated with device explantation in paediatric and adult CIs. Ch.: characteristic; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; R/S: receiver/stimulator.

Figure 3. Distribution of treatments used for all complications in the paediatric and adult groups. Minor complications were treated conservatively, while major complications were mainly treated by hospitalisation, surgical revision, or CI explantation with or without reimplantation. Drugs: home prescription drugs; Outpatient: outpatient clinic; Hospitalisation: infusion drugs and observation; E.: explantation.

| Article | No. patients (No. cochlear implants) | % complications | % major | % minor | Follow-up in years: mean (range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gysin 2000 12 | 104 | 9 | 6 | 3 | / |

| Green 2004 13 | 240 [A] | 54 | 28.6 | 25.4 | / |

| Bhatia 2004 14 | 300 [P] | 18.3* | 2.3* | 16* | 4 (0.1-14) |

| Arnolder 2005 15 | 292(342) | 15.2 | 11.1 | 4 | / |

| Dutt 2005 16 | 100(122) | (21.2) | (3.2) | (31) | |

| Kandogan 2005 17 | 205(227) [P] | (18.9) | (12.3) | (6.6) | / |

| Lin 2006 18 | 169 [P] | (15.9) | / | / | (3-11) |

| Stratigouleas 2006 19 | 176 | 12.5 | 4 | 8.5 | 0.7 |

| Kim 2008 20 | 720 | 9.3 | 4.2 | 5.1 | 3.5 (0.3-6.7) |

| Venail 2008 21 | (500) | (16) | (10.4) | (5.6) | 6.8 (0.8-17.8) |

| Al-Muhaimeed 2009 22 | 117 | 16.2* | 11* | 8* | / |

| Migirov 2009 23 | 257 | 26.8* | /* | /* | / |

| Hansen 2010 24 | 367(505) | 29.1 | 1.8 | 12.5 (9.1) | 3 |

| Loundon 2010 25 | 434 [P] | 9.9* | 5.5* | 4.4* | 5.5 (0-17) |

| Ajallouyean 2011 26 | 262 [P] | 19.1* | 0.4* | 18.7* | / |

| Pirzadeh 2011 27 | 177 | 13.6 | 4.5 | 9 | / |

| Qiu 2011 28 | 416 | 7* | 1.5* | 5.5* | 2.6 |

| Raghunandhan 2011 29 | 300 | 30.6 | 10 | 21 | / |

| Stamatiou 2011 30 | 212 [A] | 5.7 | 4.7 | 1 | > 0.5 |

| Chen 2013 31 | 445 [older A] | 13.9 | 4.7 | 9.2 | 4.8 (0.1-12.5) |

| Jeppesen 2013 2 | 269 [A] | 62.5* | 8.6* | 59* | 5 (0-17.5) |

| Tarkan 2013 32 | 475 | 9 | 4.4 | 4.6 | (0.4-12) |

| Farinetti 2014 33 | 403 | 19.9 | 5 | 14.9 | 7.5 |

| Olgun 2014 34 | 957 (1421) [P] | (2.5) | 16 | 10 | 5.4 (1-14) |

| Alcas 2016 35 | 107 | 18.7 | 3.7 | 14.9 | > 0.2 |

| Jiang 2017 36 | 1014 (1065) | (2.6) | 7 | 21 | 3.5 (0.7-9) |

| Sivam 2017 37 | (579) [P] | (23) | / | / | / |

| Awad 2018 38 | 163 | 10.4 | 3.6 | 6.7 | / |

| Shiras 2018 39 | 213 [P] | 7.5 | 2.3 | 5.1 | / |

| Theunisse 2018 40 | 1222 (1362) | (21.3) | (6.6) | (14.5) | 7.9 (0.1-27.2) |

| Binnetoglu 2020 41 | 2597 | 3.7 | 0.7 | 3 | 8.8 (1.2-17) |

| Dagkiran 2020 42 | 1357 (1452) | 10.1 | 4.7 | 5.4 | (0.2-19) |

| Ahmed 2021 43 | 251 [P] | 6.4 | 1.6 | 4.8 | / |

| Garrada 2021 44 | 148 | 18.9 | 7.4 | 11.5 | 5.6 (1-20) |

| Shi 2021 45 | (624) | (6.8) | (1.4) | (5.4) | > 0.2 |

| Castro 2022 46 | 432 | 15.5 | 5.4 | 12 | / |

| Mathews 2023 47 | (1250) | (15) | (9) | (6) | / |

| Shahabaddin 2024 48 | (160) | (10) | (2.5) | (7.5) | / |

| Present study | 1329 (2000) | 11.2 (9.8) | 4.8 (4.2) | 6.3 (5.5) | 11.6 (0.3-31.6) |

| In parentheses “()”: when referring to number of cochlear implants instead of number of patients; [A]: only adult population; [P]: only paediatric population; *device related complications excluded or not mentioned; /: data not mentioned. | |||||

References

- European consensus statement on cochlear implant failures and explantations. Otol Neurotol. 2005;26:1097-1099.

- Jeppesen J, Faber C. Surgical complications following cochlear implantation in adults based on a proposed reporting consensus. Acta Otolaryngol. 2013;133:1012-1021. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/00016489.2013.797604

- Colletti V, Carner M, Miorelli V. Cochlear implantation at under 12 months: report on 10 patients. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:445-449. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlg.0000157838.61497.e7

- De Raeve L, Archbold S, Lehnhardt-Goriany M. Prevalence of cochlear implants in Europe: trend between 2010 and 2016. Cochlear Implants Int. 2020;21:275-280. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14670100.2020.1771829

- Web Annexes. Geneva: World Health Organization. Published online 2021.

- Wang J, Wang A, Psarros C. Rates of revision and device failure in cochlear implant surgery: a 30-year experience. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:2393-2399. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.24649

- Ray J, Gibson W, Sanli H. Surgical complications of 844 consecutive cochlear implantations and observations on large versus small incisions. Cochlear Implants Int. 2004;5:87-95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1179/cim.2004.5.3.87

- Jinka S, Wase S, Jeyakumar A. Complications of cochlear implants: a MAUDE database study. J Laryngol Otol. 2023;137:1267-1271. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022215123000828

- Parent V, Codet M, Aubry K. The French Cochlear Implant Registry (EPIIC): cochlear implantation complications. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2020;137:S37-S43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anorl.2020.07.007

- House J, Brackmann D. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1985;93:146-147. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/019459988509300202

- Trotter M, Backhouse S, Wagstaff S. Classification of cochlear implant failures and explantation: the Melbourne experience, 1982-2006. Cochlear Implants Int. 2009;10:105-110. doi:https://doi.org/10.1179/cim.2009.10

- Gysin C, Papsin B, Daya H. Surgical outcome after paediatric cochlear implantation: diminution of complications with the evolution of new surgical techniques. J Otolaryngol. 2000;29:285-289.

- Green K, Bhatt Y, Saeed S. Complications following adult cochlear implantation: experience in Manchester. J Laryngol Otol. 2004;118:417-420. doi:https://doi.org/10.1258/002221504323219518

- Bhatia K, Gibbin K, Nikolopoulos T. Surgical complications and their management in a series of 300 consecutive pediatric cochlear implantations. Otol Neurotol. 2004;25:730-739. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00129492-200409000-00015

- Arnoldner C, Baumgartner W, Gstoettner W. Surgical considerations in cochlear implantation in children and adults: a review of 342 cases in Vienna. Acta Otolaryngol. 2005;125:228-234.

- Dutt S, Ray J, Hadjihannas E. Medical and surgical complications of the second 100 adult cochlear implant patients in Birmingham. J Laryngol Otol. 2005;119:759-764. doi:https://doi.org/10.1258/002221505774481291

- Kandogan T, Levent O, Gurol G. Complications of paediatric cochlear implantation: experience in Izmir. J Laryngol Otol. 2005;119:606-610. doi:https://doi.org/10.1258/0022215054516331

- Lin Y, Lee F, Peng S. Complications in children with long-term cochlear implants. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2006;68:237-242. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000092339

- Stratigouleas E, Perry B, King S. Complication rate of minimally invasive cochlear implantation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135:383-386. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otohns.2006.03.023

- Kim C, Oh S, Chang S. Management of complications in cochlear implantation. Acta Otolaryngol. 2008;128:408-414. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00016480701784973

- Venail F, Sicard M, Piron J. Reliability and complications of 500 consecutive cochlear implantations. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;134:1276-1281. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/archoto.2008.504

- Al-Muhaimeed H, Al-Anazy F, Attallah M. Cochlear implantation at King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: a 12-year experience. J Laryngol Otol. 2009;123. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022215109991095

- Migirov L, Dagan E, Kronenberg J. Surgical and medical complications in different cochlear implant devices. Acta Otolaryngol. 2009;129:741-744. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00016480802398954

- Hansen S, Anthonsen K, Stangerup S. Unexpected findings and surgical complications in 505 consecutive cochlear implantations: a proposal for reporting consensus. Acta Otolaryngol. 2010;130:540-549. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/00016480903358261

- Loundon N, Blanchard M, Roger G. Medical and surgical complications in pediatric cochlear implantation. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136:12-15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/archoto.2009.187

- Ajallouyean M, Amirsalari S, Yousefi J. A report of surgical complications in a series of 262 consecutive pediatric cochlear implantations in Iran. Iran J Pediatr. 2011;21:455-460.

- Pirzadeh A, Khorsandi M, Mohammadi M. Complications related to cochlear implants: experience in Tehran. J Pak Med Assoc. 2011;61:622-624.

- Qiu J, Chen Y, Tan P. Complications and clinical analysis of 416 consecutive cochlear implantations. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;75:1143-1146. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2011.06.006

- Raghunandhan S, Kameswaran M, Anand Kumar R. A study of complications and morbidity profile in cochlear implantation: the MERF experience. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;66:161-168. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12070-011-0387-3

- Stamatiou G, Kyrodimos E, Sismanis A. Complications of cochlear implantation in adults. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2011;120:428-432. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/000348941112000702

- Chen D, Clarrett D, Li L. Cochlear implantation in older adults: long-term analysis of complications and device survival in a consecutive series. Otol Neurotol. 2013;34:1272-1277. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0b013e3182936bb2

- Tarkan Ö, Tuncer Ü, Özdemir S. Surgical and medical management for complications in 475 consecutive pediatric cochlear implantations. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;77:473-479. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2012.12.009

- Farinetti A, Ben Gharbia D, Mancini J. Cochlear implant complications in 403 patients: comparative study of adults and children and review of the literature. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2014;131:177-182. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anorl.2013.05.005

- Olgun Y, Bayrak A, Catli T. Pediatric cochlear implant revision surgery and reimplantation: an analysis of 957 cases. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;78:1642-1647. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2014.07.013

- Alcas O, Salazar M. Complications of cochlear implant surgery: a ten-year experience in a referral hospital in Peru, 2006-2015. Cochlear Implants Int. 2016;17:238-242. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14670100.2016.1219480

- Jiang Y, Gu P, Li B. Analysis and management of complications in a cohort of 1,065 minimally invasive cochlear implantations. Otol Neurotol. 2017;38:347-351. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000001302

- Sivam S, Syms C, King S. Consideration for routine outpatient pediatric cochlear implantation: a retrospective chart review of immediate post-operative complications. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;94:95-99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.12.018

- Awad A, Rashad U, Gamal N. Surgical complications of cochlear implantation in a tertiary university hospital. Cochlear Implants Int. 2018;19:61-66. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14670100.2017.1408231

- Shiras S, Vaid N, Vaid S. Surgical complications and their management in cochlear implantees less than 5 years of age: the KEMH Pune experience. Cochlear Implants Int. 2018;19:67-71. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14670100.2017.1407521

- Theunisse H, Pennings R, Kunst H. Risk factors for complications in cochlear implant surgery. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;275:895-903. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-018-4901-z

- Binnetoglu A, Demir B, Batman C. Surgical complications of cochlear implantation: a 25-year retrospective analysis of cases in a tertiary academic center. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;277:1917-1923. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-05916-w

- Dağkıran M, Tarkan Ö, Sürmelioğlu Ö. Management of complications in 1452 pediatric and adult cochlear implantations. Turk Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;58:16-23. doi:https://doi.org/10.5152/tao.2020.5025

- Ahmed J, Saqulain G, Khan M. Complications of cochlear implant surgery: a public implant centre experience. Pak J Med Sci. 2021;37:1519-1523. doi:https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.37.5.3960

- Garrada M, Alsulami M, Almutairi S. Cochlear implant complications in children and adults: retrospective analysis of 148 cases. Cureus. 2021;13. doi:https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.20750

- Shi L, Zhu G, Ma D. Delayed postoperative complications in 624 consecutive cochlear implantation cases. Acta Otolaryngol. 2021;141:663-670. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00016489.2021.1942194

- Castro G, Santiago H, Aguiar R. Cochlear implant complications in a low-income area of Brazil. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2022;68:568-573. doi:https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9282.20210924

- Mathews S, Karthikeyan K, Arumugam S. Complication profile in a cochlear implantation – surgical audit in a large study population of low socio-economic status in a developing country. Cochlear Implants Int. 2023;24:283-291. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14670100.2023.2233212

- Shahabaddin L, Al-Jaaf S, Emin A. Intraoperative difficulties and postoperative complications associated with cochlear implantations: a study from Erbil city. Cureus. 2024;16. doi:https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.52106

- Cohen N, Hoffman R. Complications of cochlear implant surgery in adults and children. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1991;100(9 Pt 1):708-711. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/000348949110000903

- Chauhan V, Vishwakarma R. CSF gusher and its management in cochlear implant patient with enlarged vestibular aqueduct. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;71:315-319. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12070-019-01696-w

- Vashist S, Singh S. CSF gusher in cochlear implant surgery-does it affect surgical outcomes?. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2016;133:S21-S24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anorl.2016.04.010

- Hashemi S, Bozorgi H, Kazemi T. Cerebrospinal fluid gusher in cochlear implant and its associated factors. Acta Otolaryngol. 2020;140:621-625. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00016489.2020.1751276

- Hongjian L, Guangke W, Song M. The prediction of CSF gusher in cochlear implants with inner ear abnormality. Acta Otolaryngol. 2012;132:1271-1274. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/00016489.2012.701328

- Benchetrit L, Jabbour N, Appachi S. Cochlear implantation in pediatric patients with enlarged vestibular aqueduct: a systematic review. Laryngoscope. 2022;132:1459-1472. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.29742

- Choi B, An Y, Song J. Clinical observations and molecular variables of patients with hearing loss and incomplete partition type III. Laryngoscope. 2016;126:E123-E128. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.25573

- Shin T, Totten D, Tucker B. Cochlear implant electrode misplacement: a case series and contemporary review. Otol Neurotol. 2022;43:547-558. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000003503

- Mecca M, Wagle W, Lupinetti A. Complication of cochlear implantation surgery. Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:2089-2091.

- Tange R, Grolman W, Maat A. Intracochlear misdirected implantation of a cochlear implant. Acta Otolaryngol. 2006;126:650-652. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00016480500445206

- Migirov L, Taitelbaum-Swead R, Hildesheimer M. Revision surgeries in cochlear implant patients: a review of 45 cases. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264:3-7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-006-0144-5

- Ziylan F, Smeeing D, Bezdjian A. Feasibility of preservation of chorda tympani nerve during noninflammatory ear surgery: a systematic review. Laryngoscope. 2018;128:1904-1913. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26970

- Blijleven E, Wegner I, Stokroos R. The impact of injury of the chorda tympani nerve during primary stapes surgery or cochlear implantation on taste function, quality of life and food preferences: a study protocol for a double-blind prospective prognostic association study. PLoS One. 2023;18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0284571

- Hohman M, Bhama P, Hadlock T. Epidemiology of iatrogenic facial nerve injury: a decade of experience. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:260-265. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.24117

- Dogiparthi J, Teru S, Lomiguen C. Iatrogenic facial nerve injury in head and neck surgery in the presence of intraoperative facial nerve monitoring with electromyography: a systematic review. Cureus. 2023;15. doi:https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.48367

- Hsieh H, Wu C, Zhuo M. Intraoperative facial nerve monitoring during cochlear implant surgery: an observational study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000000456

- Mandour M, Khalifa M, Khalifa H. Iatrogenic facial nerve exposure in cochlear implant surgery: incidence and clinical significance in the absence of intra-operative nerve monitoring. Cochlear Implants Int. 2019;20:250-254. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14670100.2019.1625126

- Ishikawa Y, Hosoya M, Kanzaki S. Delayed facial palsy after cochlear implantation caused by reactivation of Herpesvirus: a case report and review of the literature. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2022;49:880-884. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anl.2021.03.001

- Sahai I, Ghosh B, Anjankar A. A spectrum of intraoperative and postoperative complications of cochlear implants: a critical review. Cureus. 2022;14. doi:https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.28151

- Shaida Z, Magos T, Kanona H. Recurrent swelling in pediatric cochlear implant patients. Otol Neurotol. 2023;44:E300-E304. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000003881

- Kwok B, Young A, Kong J. Post cochlear implantation vertigo: ictal nystagmus and audiovestibular test characteristics. Otol Neurotol. 2024;45:65-74. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000004037

- Katsiari E, Balatsouras D, Sengas J. Influence of cochlear implantation on the vestibular function. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270:489-495. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-012-1950-6

- Quimby A, Grose E, Reddy D. Predictors of surgical site infection in pediatric cochlear implantation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;168:484-490. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/01945998221104933

- Chen J, Chen B, Shi Y. A retrospective review of cochlear implant revision surgery: a 24-year experience in China. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2022;279:1211-1220. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-021-06745-1

- Moon P, Qian Z, Ahmad I. Infectious complications following cochlear implant: risk factors, natural history, and management patterns. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;167:745-752. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/01945998221082530

- Vijendren A, Ajith A, Borsetto D. Cochlear implant infections and outcomes: experience from a single large center. Otol Neurotol. 2020;41:E1105-E1110. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000002772

- Sykopetrites V, Di Maro F, Sica E. Acquired cholesteatoma after cochlear implants: case series and literature review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2024;281:1285-1291. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-023-08251-y

- Lee S, Lee J, Chung J. Posterior tympanotomy versus subtotal petrosectomy: a comparison of complications in cochlear implantation. Otol Neurotol. 2021;42:260-265. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000002899

- Gumus B, İncesulu A, Kaya E. Analysis of cochlear implant revision surgeries. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;278:675-682. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-06121-5

- Lane C, Zimmerman K, Agrawal S. Cochlear implant failures and reimplantation: a 30-year analysis and literature review. Laryngoscope. 2020;130:782-789. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.28071

- Kim S, Kim M, Chung W. Evaluating reasons for revision surgery and device failure rates in patients who underwent cochlear implantation surgery. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;146:414-420. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0030

- Alahmadi A, Abdelsamad Y, Yousef M. Risk factors and management strategies of inadvertent facial nerve stimulation in cochlear implant recipients: a systematic review. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2023;8:1345-1356. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/lio2.1121

Downloads

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright

Copyright (c) 2025 Società Italiana di Otorinolaringoiatria e chirurgia cervico facciale

How to Cite

- Abstract viewed - 487 times

- PDF downloaded - 104 times

PDF

PDF