Rhinology

Vol. 45: Issue 1 - February 2025

Role of body mass index as a predictor of dupilumab efficacy in patients with severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps

Abstract

Objective. Response to dupilumab for chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, albeit almost always excellent, is still not predictable. Our study focuses on the role of body mass index (BMI) on the efficacy of dupilumab.

Methods. We present a retrospective multicentre study of 106 patients on dupilumab, stratified in 3 subgroups of BMI. The main therapeutic outcomes investigated were Nasal Polyp Score (NPS), Sino-Nasal-Outcome Test - 22 (SNOT-22), Sniffin’ Sticks Identification test and visuo-analogical scale, and the different timing of response, according to De Corso et al. criteria.

Results. Dupilumab treatment led to a progressive improvement for all outcomes at all time points. Comparing the different metabolic subgroups, a late response in terms of decrease in NPS was observed only in 3 obese patients. A significant decrease was also found in SNOT-22 score at 6 and 12 months, which was less marked in overweight/obese patients.

Conclusions. Our study confirmed the efficacy of dupilumab in each BMI subgroup. However, the efficacy seems to follow different timing with respect to patients’ BMI. Our data suggest that patients with a compromised metabolic state present more severe disease at baseline and a possibly delayed response to dupilumab.

Introduction

Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) is a heterogeneous, multifactorial inflammatory disease that may be characterised by a type 2 immune signature 1, being associated with hypereosinophilia, greater severity, association with Type 2 comorbidities (such as asthma or atopic dermatitis) and a high recurrence rate 2. Several cytokines are produced in the context of type 2 responses including interleukin 5 (IL-5), 13 (IL-13), and 4 (IL-4), which are produced from different immune cells including T-helper 2 cells (Th2), mast cells, and group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) 2.

The primary mechanism for the tissue remodelling and polyps arising in CRSwNP is represented by a maladaptive response to several agents such as viruses, bacteria (especially Staphylococcus aureus), fungi, smoking exposition, and respiratory allergens in the context of epithelial barrier damage 1,2. This leads to an innate immune reaction with overexpression of interleukin 33 (IL-33) and the arising of a Type 2 inflammatory reaction 2. IL-5 plays a pivotal role in eosinophil activation and acts as a survival factor; while IL-4 and IL-13 promote macrophage activation, control of mucus production, immunoglobulin E (IgE) release by B cells and mast cell degranulation 2,3. The inflammasome is a multi-protein complex that has an important role in the activation of a pro-inflammatory response in CRSwNP, enhancing the activation of caspase-1 and production of cytokines (such as interleukin 1β and 18) 4. The Nucleotide-binding domain Leucine-rich Repeat and Pyrin domain-containing receptor 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome (known as cryopyrin), a member of the family of NOD-like receptors (NLRs) was recently recognised to have a major role in promoting inflammation patterns in CRSwNP and is activated by the same trigger factors of CRSwNP (such as pathogens) 4. Furthermore, the NLRP3 inflammasome seems to induce high eosinophilic infiltration in CRSwNP in comparison to chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps (CRSsNP) 4.

Obesity is another widely studied factor that may lead to a status of chronic low-grade systemic inflammation, and, in the literature, there is some evidence of association with CRSwNP 5-8. The prevalence of overweight and obesity is constantly increasing with an epidemic trend. Inflammation patterns in obesity are characterised by the interplay between different cell types such as adipose tissue macrophages (ATM), neutrophils, eosinophils, mast cells, and dendritic cells 8. Interestingly, the role played by IL-4 and IL-5 in the downregulation of the fat tissue inflammatory response is in contrast to the pro-inflammatory action of interleukins 6 and 1 (IL-6 and IL-1), leptin, adiponectin, and necrosis tumor factor alpha (TNF-α) 9. In CRSwNP, leptin has demonstrated the ability to promote tissue migration of eosinophils, their activation, and an anti-apoptosis effect 8. It was also demonstrated that circulating levels of leptin are consistently higher in patients with CRSwNP and its receptors are present in nasal mucosa, suggesting an active role in immune-mediated response and chronic inflammation 9. Moreover, in obese patients, the NLRP3 inflammasome leads to the same pro-inflammatory effect of CRSwNP through overexpression of IL1β and IL-18 10.

The fully human monoclonal antibody dupilumab was approved and reimbursed in Italy about 2 years ago for the treatment of severe CRSwNP with or without other Type 2 comorbidities 11. It acts as an inhibitor of IL-4 and IL-13 by binding the alpha subunit of the IL-4Rα 12. Several studies have shown the efficacy of dupilumab in reducing the burden of CRSwNP (in terms of nasal polyps, nasal symptoms, and impact on quality of life) 13-15. Emerging from the increasing number of real-life studies are differences in terms of rapidity of the efficacy of dupilumab and, according to EPOS and EUFOREA criteria 1,16, different types of responses, including very early, early, and late responders 15. Since the inflammation pathways of obesity and CRSwNP may be overlapping, and in order to identify patient characteristics that may predict response to biological therapy, the aim of this study is to investigate the role played by fat tissue-related chronic inflammation and body mass index (BMI) in the efficacy of dupilumab and the timing of therapeutic responses.

Materials and methods

The study was designed as a real-life observational multicentric retrospective study including patients with severe and uncontrolled CRSwNP treated with dupilumab according to the indications of the Italian Medicines Agency. We reviewed medical charts from all patients admitted to a rhinology outpatient clinic in ASST Santi Paolo e Carlo Hospital (Milan, Italy), ASST Grande Ospedale Metropolitano Niguarda (Milan, Italy) and “A. Gemelli” University Hospital Foundation IRCCS (Rome, Italy) from 1 February 2021 to 31 August 2022.

Patients who had undergone administration of subcutaneous dupilumab 300 mg via a pre-filled auto-injector every 14 days for at least 6 months prior to consent and inclusion were included. All data were then anonymised and collected for the purpose of this study.

Inclusion criteria

- Age ≥ 18 years;

- Evidence of diffuse CRSwNP at the CT scan performed within the previous 6 months;

- Diagnosis of Type 2 inflammation (tissue eosinophils [EOS] > or = 10/hpf, or blood EOS > or = 250 EOS/μl, or total IgE > 100 U/L);

- Demonstration of severe uncontrolled CRSwNP with Nasal Polyp Score (NPS) ≥ 5 and Sino-Nasal-Outcome Test – 22 (SNOT-22) ≥ 50;

- Failure of 2 courses of oral corticosteroid therapy in the previous year and/or recurrence after endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) 16-18.

Exclusion criteria

- Non-Type 2 chronic rhinosinusitis;

- Pregnancy;

- Ongoing immunosuppressive therapy;

- Ongoing chemotherapy or radiotherapy for neoplastic disease in the last 12 months;

- Long-term systemic corticosteroid therapy for chronic autoimmune diseases.

Main investigations

Patients were evaluated as defined by our shared institutional protocol before the start of the treatment with dupilumab (baseline, V0) and after 1 (V1), 3 (V3), 6 (V6), and 12 (V12) months from the first administration.

Detailed information on age, gender, smoking, height (m), weight (kg), BMI (kg/m2), peripheral blood hyper-eosinophilia (EOS x 109/L), previous ESS, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) intolerance, presence of asthma as Type 2 comorbidity and presence of Widal triad were collected at the baseline.

At each examination the centres furthermore evaluated:

- NPS via endoscopy;

- Quality of life assessment with SNOT-22 questionnaire;

- Asthma Control Test (ACT) questionnaire;

- Visuo-Analogical Scale (VAS) for olfaction;

- Smell functioning assessment through olfactometry with Sniffin’ Sticks-16 identification (SSIT-16) test (Burghart®);

- Complete blood count for evaluation of blood eosinophils.

Evaluation of dupilumab efficacy

According to EPOS 2020 criteria 1,15,16,17, efficacy was described as following:

- NPS reduction (by at least one point);

- SNOT-22 reduction (by at least 8.9 points);

- Improvement of the sense of smell (using VAS and olfactometry);

- Reduction in the need for oral corticosteroids;

- Reduction of the impact of comorbidities.

Depending on the onset time of the response, we grouped patients into:

- Very early responders, if the efficacy of the treatment appeared within 30 days from treatment start;

- Early responders, if the efficacy appeared between one and 6 months;

- Late responders, if the efficacy appeared between 6 and 12 months.

According to weight and BMI, we divided our sample into three different groups, with the purpose of investigating the indirect role played by chronic inflammation of adipose tissue:

- Normal weight (BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 kg/m2);

- Overweight (BMI between 25 and 29.9 kg/m2);

- Obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2).

Statistical analysis

Data were collected in a shared Microsoft Excel 365 database and analysed with SPSS, Version 28 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, US). All variables were compared first between patients with BMI < 25 and patients with BMI > 25. The latter group was further divided into patients with BMI between 25 and 30, and patients with BMI > 30. Dichotomic variables (gender, smoke, asthma, anosmia) were compared with a chi-square test. For continuous variables (age, height, weight, BMI, ACT, VAS for the sense of smell, NPS, and SNOT-22 score, at different time points when available) we used non-parametric tests. Two-group comparisons for continuous variables were performed with a Mann-Whitney U test, while 3-group comparisons were accomplished with a Kruskal-Wallis test.

Results

This multicentric study collected the medical records of 106 patients affected by severe uncontrolled CRSwNP who received treatment with dupilumab. Data at baseline evaluation are summarised in Table I. We performed a Chi Square test for different variables, such as gender (p = 0.872), allergy (p = 0.101), presence of asthma (p = 0.894), smoking habit (p = 0.338), previous ESS (p = 0.466) and NSAID intolerance for the three metabolic groups. A significant difference (p < 0.05) was found for the presence of NSAID intolerance, but it is mandatory to underline that no obese patients were NSAID intolerant.

Efficacy of dupilumab

The response to treatment was evaluated through SNOT-22 score, NPS, sense of smell VAS, olfactometry with 16-items Sniffin’ Sticks test at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months of therapy in comparison to baseline values. Recordings on ACT and peripheral blood hypereosinophilia reduction were collected only at baseline, V6, and V12. All data are summarised in Table II.

Dupilumab showed efficacy in NPS, SNOT-22 score, sense of smell VAS, and ACT at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months of treatment in all patients. Furthermore, an improvement in SSIT-16 scores was observed during the study period. A fluctuation in the number of peripheral eosinophils was observed during the entire follow-up time. In fact, after an initial increase in their average rates at V6, a progressive reduction was noticed at V12 with values substantially comparable to the baseline.

Efficacy of dupilumab by metabolic profile (BMI)

We designed a statistical model that compared three subpopulations of patients (classified as normal weight, overweight and obese) and their response to biological therapy with dupilumab.

According to EPOS 2020 1 and De Corso et al. 15 criteria of efficacy and response to dupilumab were described as a decrease of at least one point of NPS or at least 8.9 points of SNOT-22 1,15. In our sample and for the three different metabolic subgroups, a late response in terms of NPS decrease, was observed only in 3 patients, all belonging to the obese group. Data are summarised in Tables III, IV and V. Taking into consideration the modification of SNOT-22, NPS, ACT, SSIT-16 performances, VAS for sense of smell and blood eosinophil count at all time points, no significant difference was observed among the 3 subgroups (p = 0.668, 0.24, 0.789, 0.349, 0.158 and 0.171, respectively). Taking for granted the absence of late responders among normal weight-overweight-obese patients, a Fisher test was performed with no evidence of a significant difference between very early and early responders for different weight classes.

A Chi-Square test was performed with no evidence of a significant difference in terms of response among the 3 subgroups (p = 0.196).

IMPACT OF DUPILUMAB ON NPS BY METABOLIC PROFILE

At baseline, mean values of 5.9 ± 1.9 for the “normal weight” group, 5.9 ± 1.5 for the “overweight group” and 6.6 ± 1.2 for the “obese group” were observed. Higher NPS was found in the overweight and obese groups, but no significant difference. The decrease in NPS during biological therapy in the three groups is summarised in Table V. Despite a reduction in NPS during follow-up and a lower mean value in normal weight patients, there was no significant difference between groups. Considering only 2 groups, one composed of normal weight patients and the other by overweight/obese patients, there was no significant differences at any time point.

IMPACT OF DUPILUMAB ON QUALITY OF LIFE BY METABOLIC PROFILE

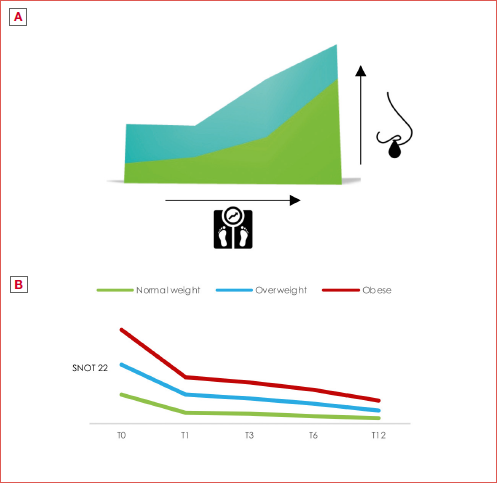

Quality of life (QoL) was assessed with the SNOT-22 questionnaire. At baseline, the average scores were 61.2 ± 20.3 for the normal weight group, 61.2 ± 19.1 for the overweight group and 66.3 ± 17.3 for the obese group. The trend in the SNOT-22 score for the 3 groups is shown in Table V, Figure 1, and Cover figure.

After Bonferroni correction, a significant decrease in SNOT-22 values was observed only between obese and normal-weight patients at V12 (Figs. 2-3). At 12 months, normal weight and overweight patients had a convergence in responses in comparison to the obese sample, as shown in Cover figure. By Mann-Whitney U test, a significant reduction between normal-weighted patients and overweighted/obese patients was seen only at 12 months (from p < 0.018 to p < 0.049). Furthermore, the trend in the obese sample does not converge to the other subgroups.

MODIFICATION OF OLFACTOMETRY AND VAS FOR THE SENSE OF SMELL BY METABOLIC GROUPS

Olfaction was assessed with VAS and SSIT-16. At baseline, in the normal weight group, the percentage of anosmic patients (defined as SSIT-16 score lower than 5/16) was 18%, in comparison with a percentage of 57.4% in the overweight/obese group. After one month of treatment, the percentages of anosmic patients in the 2 subgroups were respectively 10% and 19%; at V3 there were 12% of anosmics in normal weight patients and 15.3% in overweight/obese patients; at V6 the percentage of anosmic normal weight patients was of 4.4%, compared to 11.7% in the overweight/obese group. After 12 months of treatment, none of the normal-weight patients was anosmic versus 9.7% of overweight/obese patients. There was a significant difference between the 2 groups only at baseline and at 12 months (respectively, p < 0.001 and p = 0.027), while differences in all other time points were non-significant (V1, p = 0.216, V3, p = 0.672, V6, p = 0.174). Considering the VAS for the sense of smell, at baseline there was no significant difference between the three metabolic groups with mean values of VAS of 8.5 ± 2.3 (normal weight), 8.3 ± 2.3 (overweight), and 9.3 ± 0.9 (obese). In Table V data on VAS for the sense of smell and SSIT-16 are presented.

Variations in ACT and peripheral blood eosinophils during dupilumab treatment showed no evidence of a significant difference in the 3 metabolic subgroups at baseline or at V6 and V12.

Discussion

Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of dupilumab in CRSwNP 14,15,18. The SINUS-24 and SINUS-52 studies showed a significant improvement in the primary and secondary endpoints in comparison to placebo (such as nasal discharge, severity of nasal obstruction, NPS, loss of smell, and paranasal sinus opacification at CT scan) after 24 and 52 weeks of treatment 14. Moreover, the SINUS-52 study underlined that dupilumab acts against the main inflammatory Type 2 factors and agents 14. Our multicentric study collected data from 106 patients with severe and uncontrolled CRSwNP who were treated with the monoclonal antibody dupilumab. Our analysis confirmed its efficacy for all time points in the improvement of quality of life, NPS, VAS for the sense of smell, olfactory function, and ACT scores. A fluctuation in peripheral blood eosinophils was observed over the entire follow-up, but after an initial increase at V6 the mean count was substantially comparable to baseline at V12.

Of note, we evaluated the impact of the metabolic profile on the therapeutic response by analysing outcomes based on different BMI. For this reason, we designed a statistical model to compare the subpopulations of normal weight, overweight and obese patients with CRSwNP who were treated with dupilumab with the purpose of uncovering the existence of a different type of response at the biological therapy, depending on different metabolic profile. We focused on investigating variations in NPS, SNOT-22, and VAS for the sense of smell and outcomes of SSIT-16. Despite a progressive reduction of the NPS observed at all time points in the 3 groups, there was no significant difference during follow-up.

Our data did not show a significant difference between the 3 different BMI-based samples in terms of improvement of mean NPS 1,15. We only observed a slight difference in terms of response timing. Indeed, the only 3 late responders were overweight/obese patients. Future analyses on this aspect on a larger number of patients should be performed to confirm our preliminary analyses if obesity may be a factor predisposing to a late response.

The QoL outcomes from the SNOT-22 questionnaire revealed a significant improvement in terms of mean SNOT for all the 3 BMI-based samples in terms of mean SNOT-22 over the first year of treatment. Interestingly, a difference was observed in terms of mean SNOT in the 3 groups. The difference was not significant at baseline and progressively increased to reach significance at 6 and 12 months of observation (p < 0.05). This significance was confirmed by repeating the analyses and considering only 2 subgroups, namely normal weight and overweight/obese patients. This may be due to a delayed response to dupilumab in patients with an impaired metabolic profile, although future studies are required to confirm this preliminary observation. Taking into account the different characteristics of the items evaluated through the SNOT-22 questionnaire, it would be interesting to investigate what symptoms played a major influence in overweight/obese patients; in fact, the relation between metabolic disease, depression, and sleep disorders is widely recognised 19. Hence, evidence emerging from our study suggests that overweight/obese patients seem to have worse endoscopic features, higher comorbidity-associated symptoms, perception of their QoL, and olfactory performance at the baseline, with a probable slower response to dupilumab.

The role of Type 2 inflammation, the inflammasome, and obesity has been analysed in the literature. According to Pinkerton et al. 19, a positive relationship between BMI, NLRP3 inflammasome, IL-5, and IL-13 was demonstrated in obese patients with severe asthma and, in particular, obesity increases Type 2 cytokines and the NLRP3 inflammasome leading to uncontrolled and difficult-to-treat asthma. Obesity is widely recognised as a risk factor for the development of asthma; in particular, it seems to be associated with more severe and steroid-insensitive disease compared to non-obese patients 19,20. There is relevant evidence showing that the metabolic condition of overweight-obesity plays a role in the pathogenesis and severity of upper and lower respiratory disease 20 and their relation with Type 2 inflammation, which is a primary driver of CRSwNP 5,17,20. Adipose tissue promotes increased production of cytokines, adipocytokines, adiponectin, and other mediators, with relevant implications for the immune pathogenetic process 15,21. According to Nam et al. 21, there is a significant association between obesity and CRSwNP with evidence of worse symptoms such as purulent nasal discharge, olfactory dysfunction, and increased daily life disability in comparison to non-obese patients. This was confirmed in our study, wherein overweight and obese patients showed worse SNOT-22 scores and olfactometry performance at baseline. Moreover, obesity seems able to promote the appearance of nasal polyps with a reduced therapeutic response due to reduced immune function and production of several hormones 20. For example, increased serum leptin levels might promote chemotaxis of eosinophils into the nasal mucosa and polypoid tissue and their delayed apoptosis, inhibition of T-Reg lymphocyte proliferation, and amplify chronic inflammation and local oedema 13. It was demonstrated that cytokines, such as IL-4, IL-13, IL-5, and IL-33 have a pivotal role in the modulation of the Type 2 immune process even in adipose tissue 7. Interestingly, it was observed that, in a murine model, IL-4 acts in a completely different way in adipose tissue compared to intranasal tissue 6-8. In fact, it drives the polarisation of macrophages towards the M2 phenotype, which has local anti-inflammatory action and promotes insulin sensitivity through an increase in its receptors 6-8. For those reasons, an anti-IL4 agent could have a local pro-inflammatory role in the fat tissue of obese patients and this, perhaps, could promote a positive feedback mechanism that leads to a delayed response to dupilumab.

Taking into account olfaction, its dysfunction is strongly related to both CRS and obesity even if the physiopathology is not completely understood 21. Dupilumab promotes restoration of olfaction in patients with CRSwNP with a change in their olfactory condition, from anosmic to non-anosmic, in 62% of the sample 14. According to Mullol et al. 22, in CRSwNP the impairment could be related to multiple factors including higher chronic inflammation and therefore oedema of the neuroepithelium and the olfactory mucosa, changes in airflow in the olfactory cleft due to nasal polyposis, and a direct neurotoxic effect of inflammatory agents 23,24. According to the present literature, the prevalence of olfaction impairment is higher in obese patients in comparison to the normal weight population, with a direct relation to weight gain 23-25. Moreover, in obese subjects a volume reduction of the olfactory bulb was found that showed a potential negative correlation with BMI 24. In our study, we performed SSIT-16 that provided interesting information about olfactory function in different metabolic settings. From the baseline to V12, a consistently higher percentage of anosmic patients was found in the overweight/obese groups. It is remarkable that at V12 none of the normal-weight patients was anosmic versus a 9.7% of anosmic overweight/obese patients. Furthermore, overweight and obese patients showed worse VAS scores for their sense of smell at each time point. No confounding elements (such as smoking) could be found. This evidence could be considered concordant with our evaluation of the endoscopic features, as stated above, with higher NPS scores in overweight/obese patients at baseline and during follow-up as indicators of persistent altered airflow to the nasal vault. Results at V12 could, however, also be explained by the significantly higher rate of anosmia at baseline in overweight/obese patients.

Conclusions

Our study confirmed the efficacy of dupilumab for the treatment of severe uncontrolled CRSwNP with an improvement in endoscopic findings, sinonasal symptoms, and olfactory function in normal, overweight, and obese patients. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that has investigated the role of the fat tissue-related response of CRSwNP to dupilumab. In addition, our study underlines the efficacy of dupilumab in the treatment of severe and uncontrolled CRSwNP; the timing of response may be affected by the patient’s metabolic state due to a pro-inflammatory state promoted by fat tissue. Our findings suggest, in fact, that patients with a compromised metabolic state (overweight and obesity) have a more impaired baseline and could present a delayed response to dupilumab compared to normal-weight patients. Clinicians should therefore be aware of the different inflammation statuses of overweight and obese patients and consider the possible need for prolonged treatment to obtain an optimal response. Further studies are necessary to deepen the understanding of the role of metabolic status in Type 2 inflammation and CRSwNP.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

LN, EDC, CP: conceptualization, writing – original draft preparation; MB, AC, CS, GDM: data curation; AMS, FF, AF: review and editing; GF, AGD: supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Ethical consideration

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Fondazione Policlinico Gemelli (approval number: 2021/ST/294). The research was conducted ethically, with all study procedures being performed in accordance with the requirements of the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant/patient for study participation and data publication.

History

Received: November 28, 2023

Accepted: March 4, 2024

Figures and tables

Figure 1. Decrease in SNOT-22 score for groups 1 (normal weight), 2 (overweight) and 3 (obese) at V6 and V12.

Figure 2. Bonferroni correction for SNOT-22 at V6.

Figure 3. Bonferroni correction for SNOT-22 at V12.

| All patients | Normal | Overweight | Obese | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number or mean value ± standard deviation (%) | ||||

| Number of patients | 106 | 51 (48.1) | 44 (41.5) | 11 (10.3) |

| Male | 64/106 (60.3) | 31/51 (60.7) | 25/44 (56.8) | 6/11 (54.5) |

| Female | 42/106 (39.7) | 20/51(39.3) | 19/44 (43.2) | 5/11 (45.6) |

| Age | 52.9 ± 12.6 | 51.1 ± 11.9 | 54.8 ± 12.6 | 53.3 ± 15.7 |

| Smoke | 15/106 (14.1) | 10/51 (19.6) | 4/44(9) | 1/11(9) |

| Allergy* | 40/55 (72.7) | 24/29 (82.7) | 14/20(70) | 2/6 (33.3) |

| Previous endoscopic sinonasal surgery* (ESS) | 54/55 (98.1) | 29/29(100) | 19/20(95) | 6/6(100) |

| ESS = 1 | 11/54 (20.3) | 7/29 (24.1) | 5/20(25) | 1/6 (16.6) |

| ESS > 1 | 43/54 (79.6) | 22/29 (75.8) | 14/20(75) | 5/6 (83.3) |

| Metabolic evaluation | ||||

| Weight (kg) | 76.3 ± 15.2 | 67.4 ± 9.4 | 81.2 ± 10.3 | 102.6 ± 10.2 |

| Height (m) | 1.7 ± 0 | 1.7 ± 0 | 1.7 ± 0 | 1.7 ± 9 |

| BMI (kg*/m2) | 25.6 ± 4.3 | 22.7 ± 1.7 | 27 ± 1.7 | 34.5 ± 4 |

| Type 2 inflammation | ||||

| Asthma | 83/106 (78.3) | 40/51 (78.4) | 34/44 (77.1) | 9/11 (81.8) |

| NSAID intolerance* | 29/55 (27.3) | 19/29 (65.5) | 10/20(50) | 0/6 |

| Widal triad* | 26/55 (47.2) | 18/29(62) | 8/20(40) | 0/6 |

| * Data collected only from ASST Santi Paolo e Carlo Hospital and ASST Grande Ospedale Metropolitano Niguarda samples. | ||||

| Baseline (V0) (mean ± SD) | V1 (mean ± SD) | V3 (mean ± SD) | V6 (mean ± SD) | V12 (mean ± SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNOT-22 score | 61.7 ± 19.4 | 30.8 ± 20.2 | 25.1 ± 18.4 | 20.9 ± 16 | 13.5 ± 9.5 |

| NPS | 6 ± 1.5 | 3.5 ± 2.2 | 3 ± 2.2 | 2.4 ± 1.8 | 1.8 ± 1.6 |

| Sense of smell VAS | 8.6 ± 2.2 | 5.5 ± 3.1 | 4.2 ± 2.9 | 3.3 ± 2.7 | 2.9 ± 2.7 |

| Olfactometry with SSIT-16 | 4.5 ± 3.4 | 9.2 ± 4.1 | 9.4 ± 4.1 | 9.7 ± 3.3 | 10.4 ± 3.6 |

| ACT | 20.3 ± 4.5 | 22.8 ± 2.4 | 23 ± 2 | ||

| Blood EOS (EOSx109/L) | 0.6 ± 0.6 | 0.9 ± 0.7 | 0.7 ± 0.6 | ||

| SNOT-22: Sino-nasal Outcome Test-22; NPS: Nasal Polyp Score; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale; SSIT-16: 16 items Sniffin Sticks Identification Test; ACT: Asthma Control Test; EOS: eosinophils. | |||||

| Baseline (V0) (mean ± SD) | V1 (mean ± SD) | V3 (mean ± SD) | V6 (mean ± SD) | V12 (mean ± SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNOT-22 score – Normal weight group | 61.2 ± 20.3 | 25.3 ± 14.6 | 20.9 ± 14.4 | 16.6 ± 14.2 | 11.3 ± 8.1 |

| SNOT-22 score – Overweight group | 61.2 ± 19.1 | 36.2 ± 24 | 28.4 ± 20.8 | 24.3 ± 16.9 | 14.5 ± 10.8 |

| SNOT-22 score – Obese group | 66.3 ± 17.3 | 34.6 ± 21.1 | 32.6 ± 22.8 | 28.5 ± 16.4 | 20.3 ± 6.2 |

| NPS - Normal weight group | 5.9 ± 1.5 | 3.4 ± 1.9 | 2.8 ± 1.7 | 2.3 ± 1.6 | 1.5 ± 1.3 |

| NPS – Overweight group | 5.9 ± 1.5 | 3.4 ± 2.5 | 3.1 ± 2.5 | 2.5 ± 2 | 2 ± 1.7 |

| NPS – Obese group | 6.6 ± 1.2 | 4.1 ± 2.1 | 3.5 ± 2.6 | 2.7 ± 2.6 | 2.1 ± 2.4 |

| Sense of smell VAS – Normal weight group | 8.5 ± 2.3 | 5.2 ± 2.8 | 3.9 ± 2.9 | 3.1 ± 2.8 | 2.6 ± 2.6 |

| Sense of smell VAS – Overweight group | 8.3 ± 2.3 | 5.7 ± 3.4 | 4.3 ± 2.9 | 3.3 ± 2.6 | 3.1 ± 2.8 |

| Sense of smell VAS – Obese group | 9.3 ± 0.9 | 6.2 ± 3.5 | 4.8 ± 3.4 | 4.3 ± 3 | 3.8 ± 3.3 |

| Olfactometry with SSIT-16 – Normal weight group | 4.5 ± 3.4 | 9.1 ± 4.3 | 9.4 ± 4.5 | 10.1 ± 3.7 | 11.4 ± 3.7 |

| Olfactometry with SSIT-16 – Overweight group | 5 ± 3.6 | 9.3 ± 3.7 | 9.6 ± 3.6 | 9.5 ± 2.6 | 9.6 ± 3.1 |

| Olfactometry with SSIT-16 – Obese group | 2.7 ± 2.1 | 9.5 ± 5.5 | 9 ± 5.1 | 9 ± 3.9 | 8.8 ± 4.8 |

| ACT – Normal weight group | 20.4 ± 4.7 | 22.7 ± 2.4 | 23 ± 2.1 | ||

| ACT – Overweight group | 19.9 ± 5 | 22.6 ± 2.6 | 22.8 ± 2.1 | ||

| ACT – Obese group | 21.1 ± 2.6 | 23.6 ± 1.2 | 23.8 ± 1.7 | ||

| Blood EOS (EOSx109/L)- Normal weight | 0.6 ± 0.8 | 1 ± 0.7 | 0.8 ± 0.5 | ||

| Blood EOS – Overweight group | 0.6 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.6 | 0.6 ± 0.6 | ||

| Blood EOS – Obese Group | 0.4 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.7 | 0.6 ± 0.5 | ||

| SNOT-22: Sino-nasal Outcome Test-22; NPS: Nasal Polyp Score; ACT: Asthma Control Test; SSIT-16: 16 items Sniffin Sticks Identification Test; EOS: eosinophils. | |||||

| SNOT-22 | Very early responders | Early responder | Late responder |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 95/106 (89.6%) | 11/106 (10.3%) | 0 |

| Normal weight | 47/95 (49.4%) | 4/11 (36.3%) | 0 |

| Overweight | 39/95 (41%) | 5/11 (45.4%) | 0 |

| Obese | 9/95 (9.4%) | 2/11 (18.1%) | 0 |

| NPS | Very early responders | Early responder | Late responder |

| Overall | 89/106 (83.9%) | 14/106 (13.2%) | 3/106 (2.8%) |

| Normal weight | 48/89 (53.9%) | 3/14 (21.4%) | 0 |

| Overweight | 33/89 (37%) | 9/14 (64.2%) | 2/3 (66.6%) |

| Obese | 8/89 (9%) | 2/14 (14.3%) | 1/3 (33.3%) |

| SNOT-22: Sino-nasal Outcome Test-22; NPS: Nasal Polyp Score. | |||

| NPS | V1 (mean ± SD) | V3 (mean ± SD) | V6 (mean ± SD) | V12 (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal weight | 3.4 ± 1.9 | 2.8 ± 1.7 | 2.3 ± 1.6 | 1.5 ± 1.3 |

| Overweight | 3.4 ± 2.5 | 3.1 ± 2.5 | 2.5 ± 2 | 2 ± 1.7 |

| Obese | 4.1 ± 2.1 | 3.5 ± 2.6 | 2.6 ± 2.6 | 2.1 ± 2.6 |

| p value (< 0.05) | .604 | .725 | 7.9 | 5.2 |

| SNOT-22 | V1 (mean ± SD) | V3 (mean ± SD) | V6 (mean ± SD) | V12 (mean ± SD) |

| Normal weight | 25.3 ± 14.6 | 20.9 ± 14.4 | 16.6 ± 14.2 | 11.3 ± 8.1 |

| Overweight | 36.2 ± 24 | 28.4 ± 20.8 | 24.3 ± 16.9 | 14.5 ± 10.8 |

| Obese | 34.6 ± 31.1 | 32.6 ± 22.8 | 28.5 ± 16.4 | 20.3 ± 6.2 |

| p value (< 0.05) | .070 | .078 | .020 | .018 |

| VAS for smell | V1 (mean ± SD) | V3 (mean ± SD) | V6 (mean ± SD) | V12 (mean ± SD) |

| Normal weight | 5.2 ± 2.8 | 3.9 ± 2.9 | 3.1 ± 2.8 | 2.6 ± 2.6 |

| Overweight | 5.7 ± 3.4 | 4.3 ± 2.9 | 3.3 ± 2.6 | 3.1 ± 2.8 |

| Obese | 6.2 ± 3.5 | 4.8 ± 3.4 | 4.3 ± 3 | 3.8 ± 3.3 |

| p value (< 0.05) | .363 | .515 | .302 | .358 |

| SSIT-16** | V1 (mean ± SD) | V3 (mean ± SD) | V6 (mean ± SD) | V12 (mean ± SD) |

| Normal weight | 9.1 ± 4.3 | 9.4 ± 4.5 | 10.1 ± 3.7 | 11.3 ± 3.7 |

| Overweight | 9.3 ± 3.7 | 9.6 ± 3.6 | 9.5 ± 2.7 | 9.6 ± 3.1 |

| Obese | 9.5 ± 5.5 | 9 ± 5.1 | 9 ± 3.9 | 8.8 ± 4.3 |

| p value (< 0.05) | .943 | .923 | .467 | .208 |

| NPS: Nasal Polyp Score; SNOT-22: Sino-nasal Outcome Test-22; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale; SSIT-16: 16 items - Sniffin’ Sticks Identification test. **Data collected only from ASST Santi Paolo e Carlo Hospital and “A. Gemelli” University Hospital Foundation IRCCS samples. | ||||

References

- Fokkens W, Lund V, Hopkins C. Executive summary of EPOS 2020 including integrated care pathways. Rhinology. 2020;58:82-111. doi:https://doi.org/10.4193/Rhin20.601

- Kato A. Immunopathology of chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergol Int. 2015;64:121-130. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alit.2014.12.006

- Zhang N, Van Zele T, Perez-Novo C. Different types of T-effector cells orchestrate mucosal inflammation in chronic sinus disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:961-968. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2008.07.008

- Lin H, Li Z, Lin D. Role of NLRP3 inflammasome in eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Inflammation. 2016;39:2045-2052. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10753-016-0442-z

- Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2000;894:I-XII.

- Bastard J-P, Maachi M, Lagathu C. Recent advances in the relationship between obesity, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2006;17:4-12.

- Engin A. The pathogenesis of obesity-associated adipose tissue inflammation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;960:221-245. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48382-5_9

- Cancello R, Clément K. Is obesity an inflammatory illness? Role of low-grade inflammation and macrophage infiltration in human white adipose tissue. BJOG. 2006;113:1141-1147. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01004.x

- Taildeman J, Demetter P, Rottiers I. Identification of the nasal mucosa as a new target for leptin action. Histopathology. 2010;56:789-798. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03552.x

- Vandanmagsar B, Youm Y, Ravussin A. The NLRP3 inflammasome instigates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2011;17:179-188. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.2279

- Nitro L, Bulfamante A, Rosso C. Adverse effects of dupilumab in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Case report and narrative review. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2022;42:199-204. doi:https://doi.org/10.14639/0392-100X-N1911

- Wenzel S, Ford L, Pearlman D. Dupilumab in persistent asthma with elevated eosinophil levels. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2455-2466. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1304048

- Bachert C, Mannent L, Naclerio R. Effect of subcutaneous dupilumab on nasal polyp burden in patients with chronic sinusitis and nasal polyposis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315:469-479. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.19330

- Bachert C, Han J, Desrosiers M. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in patients with severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (LIBERTY NP SINUS-24 and LIBERTY NP SINUS-52): results from two multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2019;394:1638-1650. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31881-1

- De Corso E, Settimi S, Montuori C. Effectiveness of dupilumab in the treatment of patients with severe uncontrolled CRSwNP: a “real-life” observational study in the first year of treatment. J Clin Med. 2022;11. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11102684

- Bachert C, Han J, Wagenmann M. EUFOREA expert board meeting on uncontrolled severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) and biologics: definitions and management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147:29-36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2020.11.013

- Gallo S, Russo F, Mozzanica F. Prognostic value of the SinoNasal Outcome Test 22 (SNOT-22) in chronic rhinosinusitis. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2020;40:113-121. doi:https://doi.org/10.14639/0392-100X-N0364

- De Corso E, Bellocchi G, de Benedetto M. Biologics for severe uncontrolled chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps: a change management approach. Consensus of the Joint Committee of Italian Society of Otorhinolaryngology on biologics in rhinology. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2022;42:1-16. doi:https://doi.org/10.14639/0392-100X-N1614

- Pinkerton J, Kim R, Brown A. Relationship between type 2 cytokine and inflammasome responses in obesity-associated asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149:1270-1280. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2021.10.003

- Gibeon D, Batuwita K, Osmond M. Obesity-associated severe asthma represents a distinct clinical phenotype: analysis of the British Thoracic Society Difficult Asthma Registry Patient cohort according to BMI. Chest. 2013;143:406-414. doi:https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.12-0872

- Nam J, Roh Y, Fahad W. Association between obesity and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps: a national population-based study. BMJ Open. 2021;11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047230

- Mullol J, Bachert C, Amin N. Olfactory outcomes with dupilumab in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10:1086-1095.e5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2021.09.037

- Velluzzi F, Deledda A, Onida M. Relationship between olfactory function and BMI in normal weight healthy subjects and patients with overweight or obesity. Nutrients. 2022;14. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14061262

- Poessel M, Breuer N, Joshi A. Reduced olfactory bulb volume in obesity and its relation to metabolic health status. Front Hum Neurosci. 2020;14. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2020.586998

- Hummel T, Whitcroft K, Andrews P. Position paper on olfactory dysfunction. Rhinology. 2016;54:1-30. doi:https://doi.org/10.4193/Rhino16.248

Downloads

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright

Copyright (c) 2025 Società Italiana di Otorinolaringoiatria e chirurgia cervico facciale

How to Cite

- Abstract viewed - 770 times

- PDF downloaded - 285 times