Head and neck

Vol. 45: Issue 1 - February 2025

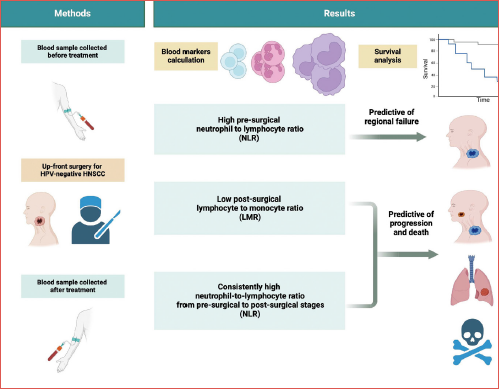

Prognostic value of changes in pre- and postoperative inflammatory blood markers in HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinomas

Abstract

Objective. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR) are inflammatory markers easily obtained from a routine complete blood count, and their preoperative values have recently been correlated with oncological outcomes in patients with HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). The aim of this study is to evaluate the prognostic value of NLR and LMR before and after treatment in patients with HPV-negative HNSCC undergoing up-front surgical treatment.

Methods. This multicentric retrospective study was performed on a consecutive cohort of patients treated by upfront surgery for HPV-negative HNSCC between April 2004 and June 2018. Only patients whose pre- and postoperative NLR and LMR were available were included. Their association with local, regional and distant failure, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) was calculated.

Results. A total of 493 patients (mean age 68 years) were enrolled. The mean follow-up time was 54 months. Pre-surgical NLR ≥ 3.76 was associated with a high risk of regional failure (HR = 2.21, 95% CI: 1.08-5.55), disease progression (HR = 1.55, 95% CI: 1.07-2.25) and death (HR = 1.40, 95% CI: 0.94-2.10). A post-surgical LMR < 2.92 had a significant impact on disease progression (HR = 1.92, 95% CI: 1.13-3.28) and OS (HR = 2.98, 95% CI: 1.53-5.81). Patients with stable NLR ≥ 3.76 in the pre- and postoperative period had worse OS and PFS.

Conclusions. Our results support that pre- and postoperative NLR and LMR can be useful in identifying patients at risk of local, regional, or distant recurrence who may require closer follow-up or more aggressive treatment.

Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) is the sixth most prevalent cancer. It affects around 890,000 people annually and caused approximately 450,000 deaths in 2018 1. In a 10-year analysis, the overall survival (OS) rate differed significantly by site. The most favourable prognosis was observed in p16+ oropharyngeal tumours with an OS rate of 87%, followed by tumours in the oral cavity at 69%, larynx at 67%, p16- oropharyngeal tumours at 56%, and hypopharynx at 51%2. Treatment options for SCC include surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or a combination of these. The type of treatment is largely determined by the traits of the presenting tumour, namely TNM stage, histological type, grade, and location, which in turn determine prognosis 3,4. Improved risk stratification is needed, considering the poor survival rates, to identify patients who have a higher risk of recurrence and to accordingly tailor treatment and surveillance 5. The German pathologist Rudolf Virchow was the first to put forward an association between cancer and inflammation in 1863, as he observed that tumours were always accompanied by inflammatory cells, but his theory did not gain much attention until the century that followed 6,7. Recent studies have confirmed the importance of the systemic inflammatory response in tumour cell invasion by promoting tumour cell proliferation, microvascular regeneration, and tumour metastasis 8,9. The tumour immune microenvironment (TIM) is the immune infiltrate that emerges during tumour growth and several reports have verified its major role in cancer progression 10. The TIM includes various tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) that have a large effect on cancer invasion and metastasis. A new pro-tumour ability of circulating neutrophils has been discovered recently, wherein they are able to trap circulating tumour cells (CTCs) and promote metastasis by facilitating their extravasation. These neutrophils are referred to as tumour-associated neutrophils (TANs) and are also known for their ability to infiltrate cancerous tissue. TANs play a crucial role in promoting tumour progression through various mechanisms, such as proliferation, angiogenesis, and interactions with other immune cells 11. Both tumour cells and the tumour microenvironment promote a systemic inflammatory response that modifies the circulating counts of lymphocytes, neutrophils, monocytes and platelets; such values may be associated with cancer prognosis when taken individually or as ratios 12,13. In patients with HNSCC, decreased levels of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ cells are observed in peripheral blood, and CD4+ levels are found to be correlated with disease stage 14. Surgical trauma can cause significant changes in the body, leading to metabolic, haemodynamic, and immune alterations during the postoperative period 15. The initial systemic inflammatory response is mediated by the innate immune system, while the anti-inflammatory response becomes more pronounced as the injury site begins to heal, primarily mediated by the adaptive immune system. After major surgery, both innate and cell-mediated immunity functions are significantly impaired. Surgery to treat HNSCC leads to multiple changes in the patient’s blood profile, including anaemia, leukocytosis, lymphopenia, thrombocytosis, increased neutrophils, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and decreased albumin levels. It has been observed that there is a decrease in the levels of various subpopulations of lymphocytes, including B lymphocytes, T helper cells, NK cells, and naïve T helper cells 16.

The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is a recent marker of host inflammation, which resembles the relation between circulating neutrophil and lymphocyte counts4 as well as lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR) 17,18 that can be easily calculated from a routine complete blood count (CBC) 19. These inflammatory markers have been reported to be prognostic indicators of survival and to be associated with clinical outcomes in patients with various types of cancer, including ovarian cancer 20, colorectal cancer 21, and head and neck cancer 22,23.

We have previously reported that pre-treatment NLR and LMR correlate with oncological outcomes in patients with HPV-negative head and neck cancer 24. These markers may change after treatment, and it is interesting to evaluate how the trajectories of such markers impact cancer outcomes. The aim of this study was therefore to investigate the prognostic value of pre- and post-treatment inflammatory NLR and LMR in patients receiving upfront surgery for HPV-negative HNSCC, with a focus on their trajectories.

Materials and methods

This is a retrospective multicentric study, whose design was described elsewhere 25. Briefly, the cohort enrolled 1001 consecutive patients diagnosed with primary HNSCC who underwent upfront surgery from April 2004 to June 2018. The study network included General and University Hospitals in Northern Italy, located in Brescia, Ferrara, Padua, Pavia, Pordenone, Treviso, Trieste, and Verona.

For the present analysis, the inclusion criteria were: (a) HNSCC arising from the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, or larynx; (b) curative upfront surgery as the primary treatment modality; (c) availability of preoperative neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, and platelet count, i.e., the blood parameters necessary for the calculation of the inflammatory blood markers under investigation; (d) availability of the same blood parameters evaluated 3-6 months after the completion of the treatment.

Patients were specifically excluded if: (a) diagnosed with nasopharyngeal carcinoma or T1 glottic SCC; (b) had any coexisting conditions or haematological conditions that could alter inflammatory parameters; (c) had a previous malignancy or additional synchronous primary tumours; (d) pre- or post-treatment blood test results were not available; (e) had metastatic disease; and (f) had HPV-positive disease.

Participants and data

Socio-demographic and clinical data were retrieved from medical records, including gender, age, smoking habits, drinking habits, cancer site, clinical and pathological TNM staging (7th edition), grading, surgical margins and extranodal extension were retrieved. For oropharyngeal carcinomas, HPV status was assessed by p16 immunostaining and/or HPV-PCR. Haemoglobin (Hb, g/L), platelets (103/μL), neutrophils (103/μL), lymphocytes (103/μL), and monocytes (103/μL) were collected at baseline before surgical treatment and at 3-6 months after the end of treatment.

Patients were routinely followed-up according to consensus guidelines with endoscopic examination of the upper aero-digestive tract every 1-3 months for the first year, 3-4 months during the second year, 4-6 months during the third year, and every 6 months thereafter. A chest computed tomography scan was performed annually in patients with a history of smoking ≥ 20 pack/years. Additional dedicated head and neck imaging was acquired based on clinical features and local protocol. No patient was lost to follow-up.

Inflammatory blood markers

Using pre- and post-treatment blood parameters, we investigated two indexes: 1) NLR, calculated as NLR= neutrophils/lymphocytes; 2) LMR, calculated as LMR= lymphocytes/monocytes. A comparison between pre- and postoperative values was also performed.

Statistical methods

Blood parameters were reported as median values and interquartile range (IQR); changes between pre- and postoperative values were evaluated through the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Correlation between pre- and postoperative indices was evaluated with Spearman’s correlation coefficient (r).

The following outcomes were assessed: a) OS defined as death from any cause; b) progression-free survival (PFS) defined as the time from surgery to any type of recurrence/progression or death from any cause; c) local failure as expression of local recurrence; d) regional failure as expression of regional recurrence; e) distant failure as expression of distant metastases. Time at risk was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of the event, date of death, or last follow-up. Survival probabilities were calculated according to Kaplan-Meier method; differences across strata were evaluated through the log-rank test. To account for competing risks, local, regional, and distant failures were evaluated through cumulative incidence, and differences according to blood parameters were tested using Gray’s test. Hazard ratios (HR) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using Cox proportional hazards models, adjusting for study centre, gender, and age, plus clinically relevant covariates (i.e., pT, pN, surgical margins, extranodal extension, adjuvant [chemo]radiotherapy). For local, regional, and distant recurrence, risk estimates were adjusted for competing risk, according to the Fine-Gray model. Blood parameters and inflammatory indexes were categorised in 3 levels, according to cut-offs previously reported 24. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.4 and R software 4.0.2 (The R foundation for statistical computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

A total of 493 patients were included (median age, 68 years; interquartile range [IQR], 60-75 years). Demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort are shown in Table I. Most patients were males (n = 366, 74.2%), with stage III-IV cancer (n = 339, 68.8%) and with moderately differentiated SCC (n = 277, 56.2%). Negative surgical margins were achieved in 353 patients (71.6%) and extracapsular extension was absent in 423 patients (85.8%). During a median follow-up of 54 months (IQR, 34-83 months), 187 patients died. Seventy patients had a local recurrence, while 68 experienced a regional recurrence, and 60 distant metastases. Baseline blood samples were obtained at a median of 20 days before surgery (IQR, 11-33 days), whereas postoperative blood samples were taken at a median of 152 days after surgery (IQR, 92-219 days).

Figure 1 shows changes in pre- and postoperative blood parameters. After surgery, a significant increase in NLR and a decrease in LMR was observed. Although significant, the variation in monocyte value is clinically negligible (median variation, -0.02 103/μL), so that the decrease in LMR is mainly due to the decrease in lymphocytes (median variation, -0.40 103/μL). Pre- and postoperative indices were moderately correlated, being r = 0.32 for NLR and r = 0.36 for LMR.

Table II shows the correlation between inflammatory index and patient outcomes. Preoperative NLR and LMR were confirmed to be prognostic markers, with similar HRs than in the wider study population 24. Specifically, NLR ≥ 3.76 was associated with high risk of regional failure (HR = 2.21, 95% CI: 1.08-5.55), disease progression (HR = 1.55, 95% CI: 1.07-2.25), and death (HR = 1.40, 95% CI: 0.94-2.10). No significant associations emerged for preoperative LMR, though the risk magnitude was similar to that reported previously 24. A postoperative LMR < 2.92 had a significant impact on disease progression (HR = 1.92, 95% CI: 1.13-3.28) and OS (HR = 2.98, 95% CI: 1.53-5.81). The same inflammatory indices with blood markers evaluated between one and 6 months after surgery are summarised in Supplementary Table I.

Patients with stable NLR ≥ 3.76 in the pre- and postoperative period had worse OS (10-year OS, 36.7%) and PFS (10-year PFS, 27.3%; Figure 2), which was much lower than those in patients with stable NLR < 3.76 (10-year OS, 53.3% and 10-year PFS, 48.1%). After adjusting for potential confounders, the HR for death and progression associated with stable NLR ≥ 3.76 were 1.87 (95% CI, 1.17-2.99) and 2.06 (95% CI, 1.35-3.14), respectively (Tab. III). Patients who had increased NLR level after surgery showed a risk of death or recurrence similar to that reported by patients with stable NLR < 3.76. Similar trends were found for a persistent LMR < 2.92 (Fig. 2, Tab. III). Interestingly, patients with a decline in LMR after surgery had an increased risk of death (HR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.14-2.63).

Discussion

The results of the present study indicate that preoperative high NLR and low LMR are negative prognostic factors in patients who underwent up-front surgery for HPV-negative HNSCC. Interestingly, the risk of death and progression increases when NLR and LMR levels persisted after surgery.

Lately there is great interest in easily obtained inflammatory biomarkers that have the ability to predict the prognosis in patients with cancer 26,27. Currently, high-risk HPV is considered a critical prognostic factor in HNSCC, and has been included in the newest TNM stage of oropharyngeal cancers. Reliable biomarkers for prognostic stratification are lacking in staging of non-HPV-related cancers. To address these issues and to analyse a more homogeneous population, in our study we selected only HPV-negative SCC. Inflammatory cells and their mediators are a prognostic tool as evidence of the immunity of the host response to cancer progression 8. The tumour microenvironment (TME) is characterised by an important inflammatory component that can induce inflammatory reactions through different mechanisms 28. Furthermore, there is a significant dialogue between the mediators and cytokines in the local TME and in the peripheral circulating compartment 29. Macrophages, the predominant cell type in chronic inflammation, produce reactive oxygen and nitrogen species to combat infections. However, their persistent presence in the microenvironment can lead to harmful effects such as DNA mutations that promote cancer. Chemicals like TNF-a and macrophage migration inhibitory factor, released by macrophages and T lymphocytes, can exacerbate DNA damage and hinder protective responses, leading to accumulation of mutations. Additionally, chronic inflammation is associated with tumour progression through processes like angiogenesis and the establishment of a tumour inflammatory microenvironment, which involves infiltration by immune cells such as tumour-associated macrophages (TAMs), mast cells, tumour-associated neutrophils (TANs), and lymphocytes, all of which contribute to tumour growth and progression 30,31. Numerous studies have examined the ability of lymphocytes, neutrophils, monocytes, LMR 32,33 and NLR to predict outcomes in patients with HNSCC. A preoperative elevated NLR 4,34-40 or a low LMR 41-45, as well as an increase in the absolute count of neutrophils39 or monocytes 46,47, or a decrease in the absolute count of lymphocytes, have been associated with poorer prognosis in many studies. Neutrophils and monocytes play a role in tumour initiation, growth, proliferation, and metastasis, while lymphocytes help to inhibit tumour development and growth through immune surveillance mechanisms.

As noted above, previous retrospective studies and meta-analyses have reported that NLR and LMR may serve as independent prognostic factors in patients with HNSCC. However, these reports were based on preoperative counts, while the dynamic changes in pre- and post-treatment values of peripheral inflammatory markers and clinical outcomes of patients with HPV-negative HNSCC undergoing curative surgery has not yet been fully investigated. A study on patients with gastric cancer found that changes in LMR after 12 months could predict long-term survival 48. Another study on gastric carcinoma revealed that high NLR and low LMR levels early after surgery were associated with complications and poor short-term outcomes 49. In breast cancer, an elevated NLR, measured around 5 years after diagnosis, was an independent risk factor for late recurrence 50. For non-small cell lung cancer patients receiving nivolumab treatment, those with an NLR greater than or equal to 5 had worse OS compared to those with an NLR less than 5 51. Additional research focusing on patients with HNSCC who underwent radiation therapy indicated that alterations in delta-LMR could potentially serve as a prognostic marker. Patients who had a high delta-LMR at 2, 4, and 6 weeks after starting treatment were found to have poorer OS and were less likely to be free from metastasis, in comparison to those with a low delta-LMR. The threshold values for delta-LMR at 2, 4, and 6 weeks were 1.5, 2.8, and 3, respectively 52. A study on patients diagnosed with SCC of the oral cavity revealed that elevated post-treatment levels of platelet count and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio serve as independent prognostic indicators of a poor outcome 53.

The results of the present study are in agreement with data in the literature that patients with high preoperative levels of NLR (> 3.76) are at a higher risk of regional failure (with HR, 2.21), disease progression, and death, while those with a low preoperative LMR (< 2.92) are at a higher risk of local failure (with HR, 1.95) according to a previous study 24 and a meta-analysis 4, regional failure, and disease progression. Additionally, has been found that changes in these markers after surgery were also associated with different outcomes. Increased NLR after surgery was associated with a reduction in OS, while a low LMR after surgery was associated with an increased risk of disease progression and reduced OS. This study also found that patients with persistently high NLR or low LMR before and after surgery were at increased risk of disease progression and reduced OS. Interestingly, even patients with a normal preoperative LMR but low LMR after surgery were found to have reduced OS. Overall, these findings suggest that monitoring these inflammatory markers before and after surgery may provide valuable prognostic information and help identify patients who may benefit from more aggressive treatment or closer follow-up.

Thus, our multicentre study has some strong points. First, we included a cohort of highly selected patients who met strict inclusion criteria and were followed with regular clinical examinations as recommended by the American Cancer Society, which allowed for a more robust analysis. Second, we utilised statistical models that yielded significant results, providing valuable insights into the data. Lastly, we compared preoperative and postoperative blood values in HNSCC, which are rarely found in the literature, further contributing to the novelty of our findings. However, a number of limitations have to be acknowledged. First, the retrospective nature of the study may have introduced some bias. Second, although blood parameters were collected before surgery to avoid the impact of the surgical procedure itself on the baseline values, it was not always possible to exclude the influence of other systemic conditions, since the parameters investigated are not specific to tumours. Furthermore, the sample size was not sufficiently large to guarantee enough power when the patients were stratified for combined pre- and postoperative parameters, as the number of events in some strata was low.

Conclusions

In summary, this study highlights the importance of monitoring NLR and LMR before and after surgery to assess prognosis in patients with HPV-negative HNSCC. The findings suggest that monitoring these markers can provide valuable information on the risk of disease progression and reduced OS and may help identify patients who require closer follow-up or more aggressive treatment. While NLR and LMR are easily calculated from standard blood tests, further studies are necessary before they can be incorporated into routine clinical practice for the management of patients with HNSCC; just as understanding the mechanisms that link inflammation and cancer progression may lead the way for the development of new therapies that target these pathways. Overall, this study provides a foundation for future research on the role of inflammatory blood markers in predicting outcomes and guiding treatment decisions in patients with HNSCC.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

The work of Dr. Giudici and Polesel was partially supported by the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Corrente).

The other authors report no involvement in the research by sponsors that could have influenced the outcome of this work.

Author contributions

TM, AM, AC, JP, DB, PBR: work conceptualisation and writing; TM, AM, GT, MT, VR, CP, MF, PN, VB, VL, FU, FT, SM, FG: data curation; JP: statistical analysis; GT, CP, PN, FT, AC, JP, DB, PBR: revision and editing. All authors have read and agree with the final version of the manuscript.

Ethical consideration

The study was conducted with the approval of the Board of Ethics of Treviso/Belluno provinces (Date March 23rd, 2020/No. 773/CE Marca). Written consent to participate was obtained from patients in accordance to Italian rules and regulations, in agreement to requirement of the Board of Ethics that approved the study.

History

Received: February 9, 2024

Accepted: May 25, 2024

Figures and tables

Figure 1. Pre- and post-treatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (A), lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (B), and selected blood markers (C-D-E).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival and progression-free survival according to pre- and post-treatment variations in neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio.

| N | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 127 | (25.8) |

| Male | 366 | (74.2) |

| Age (years) | ||

| < 60 | 113 | (22.9) |

| 60-69 | 160 | (32.5) |

| 70-79 | 152 | (30.8) |

| ≥ 80 | 68 | (13.8) |

| Smoking habits | ||

| Never | 81 | (16.4) |

| Ever | 372 | (75.5) |

| Missing | 40 | (8.1) |

| Drinking habits | ||

| Never | 261 | (52.9) |

| Ever | 164 | (33.3) |

| Missing | 68 | (13.8) |

| Cancer site | ||

| Oral cavity | 221 | (44.9) |

| Oropharynx | 59 | (12) |

| Hypopharynx | 26 | (5.3) |

| Larynx | 187 | (37.9) |

| pT | ||

| pT1 | 51 | (10.3) |

| pT2 | 174 | (35.3) |

| pT3 | 131 | (26.6) |

| pT4 | 131 | (26.6) |

| Missing | 6 | (1.2) |

| pN | ||

| pN0 | 290 | (58.8) |

| pN1 | 64 | (13) |

| pN2-pN3 | 134 | (27.2) |

| Missing | 5 | (1) |

| TNM stage | ||

| I-II | 148 | (30) |

| III | 122 | (24.8) |

| IV | 217 | (44) |

| Missing | 6 | (1.2) |

| Grading | ||

| G1 | 57 | (11.6) |

| G2 | 277 | (56.2) |

| G3 | 142 | (28.8) |

| Missing | 17 | (3.5) |

| Surgical margins | ||

| Negative | 353 | (71.6) |

| Close/positive | 128 | (26) |

| Missing | 12 | (2.4) |

| Extracapsular extension | ||

| Absent | 423 | (85.8) |

| Present | 60 | (12.2) |

| Missing | 10 | (2) |

| Pts | Local failure | Regional failure | Progression/death | Death | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events | HR (95% CI)b | Events | HR (95% CI)b | Events | HR (95% CI) | Events | HR (95% CI) | ||

| Preoperative | |||||||||

| Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio | |||||||||

| < 2.10 | 178 | 27 | Ref | 15 | Ref | 65 | Ref | 57 | Ref |

| 2.10 to < 3.76 | 213 | 26 | 0.63 (0.36-1.11) | 35 | 1.80 (0.99-3.30) | 94 | 0.94 (0.67-1.31) | 81 | 0.92 (0.65-1.32) |

| ≥ 3.76 | 102 | 17 | 0.88 (0.44-1.77) | 18 | 2.21 (1.08-5.55) | 60 | 1.55 (1.07-2.25) | 49 | 1.40 (0.94-2.10) |

| Lymphocyte-to-Monocyte Ratio | |||||||||

| ≥ 4.28 | 101 | 9 | Ref | 9 | Ref | 33 | Ref | 28 | Ref |

| 2.92 to < 4.28 | 188 | 29 | 1.64 (0.75-3.59) | 27 | 1.36 (0.63-2.94) | 81 | 1.21 (0.79-1.84) | 72 | 1.17 (0.74-1.84) |

| < 2.92 | 204 | 32 | 1.95 (0.91-4.17) | 32 | 1.55 (0.73-3.27) | 105 | 1.46 (0.96-2.21) | 87 | 1.27 (0.81-2.00) |

| Postoperative | |||||||||

| Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio | |||||||||

| < 2.10 | 154 | 22 | Ref | 22 | Ref | 59 | Ref | 47 | Ref |

| 2.10 to < 3.76 | 180 | 19 | 0.51 (0.26-0.98) | 25 | 0.76 (0.40-1.46) | 82 | 0.97 (0.68-1.37) | 72 | 1.13 (0.77-1.65) |

| ≥ 3.76 | 159 | 29 | 0.82 (0.45-1.51) | 21 | 0.64 (0.32-1.28) | 78 | 1.19 (0.83-1.71) | 68 | 1.44 (0.97-2.13) |

| Lymphocyte-to-Monocyte Ratio | |||||||||

| ≥ 4.28 | 67 | 7 | Ref | 5 | Ref | 16 | Ref | 10 | Ref |

| 2.92 to < 4.28 | 125 | 15 | 0.83 (0.33-2.10) | 22 | 1.71 (0.58-5.03) | 51 | 1.61 (0.90-2.89) | 41 | 2.18 (1.6-4.49) |

| < 2.92 | 301 | 48 | 1.03 (0.44-2.41) | 43 | 1.40 (0.50-3.90) | 152 | 1.92 (1.13-3.28) | 136 | 2.98 (1.53-5.81) |

| a Estimated from Cox proportional hazard model, adjusted for gender, age, cancer site, pT, pN, surgical margins and extracapsular extension; b Adjusted for competing risk according to the Fine-Gray model. | |||||||||

| Variation from pre- to postoperative | Pts | Local failure | Regional failure | Progression/Death | Death | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events | HR (95% CI)b | Events | HR (95% CI)b | Events | HR (95% CI) | Events | HR (95% CI) | ||

| Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio | |||||||||

| Stable < 3.76 | 279 | 33 | Ref | 38 | Ref | 111 | Ref | 94 | Ref |

| < 3.76 to ≥ 3.76 | 112 | 20 | 1.17 (0.63-2.15) | 12 | 0.59 (0.30-1.19) | 48 | 1.03 (0.72-1.47) | 44 | 1.24 (0.84-1.81) |

| ≥ 3.76 to < 3.76 | 55 | 8 | 1.05 (0.48-2.33) | 9 | 1.29 (0.60-2.80) | 30 | 1.36 (0.90-2.06) | 25 | 1.36 (0.86-2.14) |

| Stable ≥ 3.76 | 47 | 9 | 1.43 (0.65-3.12) | 9 | 1.30 (0.59-2.89) | 30 | 2.06 (1.35-3.14) | 24 | 1.87 (1.17-2.99) |

| Lymphocyte-to-Monocyte Ratio | |||||||||

| Stable ≥ 2.92 | 145 | 16 | Ref | 18 | Ref | 47 | Ref | 37 | Ref |

| ≥ 2.92 to < 2.92 | 144 | 22 | 1.01 (0.51-2.01) | 18 | 0.78 (0.39-1.56) | 67 | 1.31 (0.89-1.91) | 63 | 1.73 (1.14-2.63) |

| < 2.92 to ≥ 2.92 | 47 | 6 | 1.14 (0.46-2.83) | 7 | 1.04 (0.43-2.54) | 20 | 1.20 (0.70-2.06) | 14 | 1.10 (0.58-2.07) |

| Stable < 2.92 | 157 | 26 | 1.47 (0.74-2.90) | 25 | 1.11 (0.57-2.16) | 85 | 1.57 (1.08-2.28) | 73 | 1.68 (1.11-2.55) |

| a Estimated from Cox proportional hazard model, adjusted for gender, age, cancer site, pT, pN, surgical margins and extracapsular extension; b Adjusted for competing risk according to the Fine-Gray model. | |||||||||

References

- Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer. 2019;144:1941-1953. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.31937

- Du E, Mazul A, Farquhar D. Long-term survival in head and neck cancer: impact of site, stage, smoking, and human papillomavirus status. Laryngoscope. 2019;129:2506-2513. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.27807

- Zhou S, Yuan H, Wang J. Prognostic value of systemic inflammatory marker in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma undergoing surgical resection. Future Oncol. 2020;16:559-571. doi:https://doi.org/10.2217/fon-2020-0010

- Tham T, Bardash Y, Herman S. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic indicator in head and neck cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2018;40:2546-2557. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.25324

- Borsetto D, Tomasoni M, Payne K. Prognostic significance of CD4+ and CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13040781

- Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow?. Lancet. 2001;357:539-545. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0

- Abelardo E, Davies G, Kamhieh Y. Are inflammatory markers significant prognostic factors for head and neck cancer patients?. J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2020;82:235-244. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000507027

- Hanahan D, Weinberg R. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646-674. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013

- Hanahan D, Weinberg R. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57-70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81683-9

- Binnewies M, Roberts E, Kersten K. Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat Med. 2018;24:541-550. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0014-x

- Song Q, Wu J, Wang S. Perioperative change in neutrophil count predicts worse survival in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Future Oncol. 2021;17:4721-4731. doi:https://doi.org/10.2217/fon-2021-0371

- Takenaka Y, Oya R, Kitamiura T. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in head and neck cancer: a meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2018;40:647-655. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.24986

- Templeton A, McNamara M, Šeruga B. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:1-11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju124

- Kuss I, Hathaway B, Ferris R. Imbalance in absolute counts of T lymphocyte subsets in patients with head and neck cancer and its relation to disease. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;62:161-172. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000082506

- Greenfeld K, Avraham R, Benish M. Immune suppression while awaiting surgery and following it: dissociations between plasma cytokine levels, their induced production, and NK cell cytotoxicity. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:503-513. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2006.12.006

- Dovšak T, Ihan A, Didanovič V. Effect of surgery and radiotherapy on complete blood count, lymphocyte subsets and inflammatory response in patients with advanced oral cancer. BMC Cancer. 2018;18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4136-9

- Tazzyman S, Lewis C, Murdoch C. Neutrophils: key mediators of tumour angiogenesis. Int J Exp Pathol. 2009;90:222-231. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2613.2009.00641.x

- Mascarella M, Mannard E, Silva S. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in head and neck cancer prognosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2018;40:1091-1100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.25075

- Bojaxhiu B, Templeton A, Elicin O. Relation of baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio to survival and toxicity in head and neck cancer patients treated with (chemo-) radiation. Radiat Oncol. 2018;13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-018-1159-y

- Davis A, Afshar-Kharghan V, Sood A. Platelet effects on ovarian cancer. Semin Oncol. 2014;41:378-384. doi:https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.04.004

- Tan D, Fu Y, Su Q. Prognostic role of platelet-lymphocyte ratio in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000003837

- Rachidi S, Wallace K, Day T. Lower circulating platelet counts and antiplatelet therapy independently predict better outcomes in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Hematol Oncol. 2014;7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-014-0065-5

- Tang H, Lu W, Li B. Prognostic significance of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in biliary tract cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:36857-36868. doi:https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.16143

- Boscolo-Rizzo P, D’Alessandro A, Polesel J. Different inflammatory blood markers correlate with specific outcomes in incident HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2022;22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-022-09327-4

- Borsetto D, Sethi M, Polesel J. The risk of recurrence in surgically treated head and neck squamous cell carcinomas: a conditional probability approach. Acta Oncol. 2021;60:942-947. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2021.1925343

- Gaudioso P, Borsetto D, Tirelli G. Advanced lung cancer inflammation index and its prognostic value in HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a multicentre study. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:4683-4691. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05979-9

- Boscolo-Rizzo P, Zanelli E, Giudici F. Prognostic value of H-index in patients surgically treated for squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2021;6:729-737. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/lio2.603

- Granja S, Tavares-Valente D, Queirós O. Value of pH regulators in the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2017;43:17-34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2016.12.003

- Diakos C, Charles K, McMillan D. Cancer-related inflammation and treatment effectiveness. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:E493-E503. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70263-3

- Lu H, Ouyang W, Huang C. Inflammation, a key event in cancer development. Mol Cancer Res. 2006;4:221-233. doi:https://doi.org/10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0261

- Grivennikov S, Greten F, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883-899. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025

- Kumarasamy C, Tiwary V, Sunil K. Prognostic utility of platelet-lymphocyte ratio, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and monocyte-lymphocyte ratio in head and neck cancers: a detailed PRISMA compliant systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13164166

- Tham T, Olson C, Khaymovich J. The lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio as a prognostic indicator in head and neck cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;275:1663-1670. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-018-4972-x

- Hasegawa T, Iga T, Takeda D. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio associated with poor prognosis in oral cancer: a retrospective study. BMC Cancer. 2020;20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-07063-1

- Yin J, Qin Y, Luo Y. Prognostic value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000007577

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Farhan-Alanie O, McMahon J, McMillan D. Systemic inflammatory response and survival in patients undergoing curative resection of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;53:126-131. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjoms.2014.10.007

- Haddad C, Guo L, Clarke S. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in head and neck cancer. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2015;59:514-519. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1754-9485.12305

- Kara M, Uysal S, Altinişik U. The pre-treatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, and red cell distribution width predict prognosis in patients with laryngeal carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274:535-542. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-016-4250-8

- Rassouli A, Saliba J, Castano R. Systemic inflammatory markers as independent prognosticators of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2015;37:103-110. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.23567

- Aoyama J, Kuwahara T, Sano D. Combination of performance status and lymphocyte-monocyte ratio as a novel prognostic marker for patients with recurrent/metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer Diagn Progn. 2021;1:353-361. doi:https://doi.org/10.21873/cdp.10047

- Kano S, Homma A, Hatakeyama H. Pretreatment lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio as an independent prognostic factor for head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2017;39:247-253. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.24576

- Gao P, Peng W, Hu Y. Prognostic and clinicopathological significance of lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck. 2022;44:624-632. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.26952

- Yang J, Hsueh C, Cao W. Pretreatment lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio as an independent prognostic factor for hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Otolaryngol. 2018;138:734-740. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00016489.2018.1449965

- Tsai M, Huang T, Chuang H. Clinical significance of pretreatment prognostic nutritional index and lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in patients with advanced p16-negative oropharyngeal cancer-a retrospective study. Peer J. 2020;8. doi:https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.10465

- Valero C, Pardo L, López M. Pretreatment count of peripheral neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes as independent prognostic factor in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2017;39:219-226. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.24561

- Stroup D, Berlin J, Morton S. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008-2012. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.283.15.2008

- Zhuang Y, Yuan B, Hu Y. Pre/post-treatment dynamic of inflammatory markers has prognostic value in patients with small hepatocellular carcinoma managed by stereotactic body radiation therapy. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:10929-10937. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S231901

- Nechita V, Al-Hajjar N, Moiş E. Inflammatory ratios as predictors for tumor invasiveness, metastasis, resectability and early postoperative evolution in gastric cancer. Curr Oncol. 2022;29:9242-9254. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29120724

- Moon G, Noh H, Cho I. Prediction of late recurrence in patients with breast cancer: elevated neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) at 5 years after diagnosis and late recurrence. Breast Cancer. 2020;27:54-61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-019-00994-z

- Khunger M, Patil P, Khunger A. Post-treatment changes in hematological parameters predict response to nivolumab monotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer patients. PLoS One. 2018;13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197743

- Lin C, Chou W, Wu Y. Prognostic significance of dynamic changes in lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in patients with head and neck cancer treated with radiotherapy: results from a large cohort study. Radiother Oncol. 2021;154:76-86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2020.09.012

- Zakaria S, Ramanathan A, Mat Ripen Z. Prognostic abilities of pre- and post-treatment inflammatory markers in oral squamous cell carcinoma: stepwise modelling. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58101426

Downloads

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright

Copyright (c) 2025 Società Italiana di Otorinolaringoiatria e chirurgia cervico facciale

How to Cite

- Abstract viewed - 464 times

- PDF downloaded - 220 times

PDF

PDF