Reviews

Vol. 45: Issue 1 - February 2025

Spontaneous neck haemorrhage secondary to parathyroid adenoma: description of a case and systematic review

Abstract

Introduction. Parathyroid adenomas can rarely cause spontaneous haemorrhage, which can be life-threatening. Diagnosis is challenging. We present a case and systematic review to define a clearer pattern of symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment.

Materials and methods. We conducted a literature search of PubMed, Google Scholar, and Embase using PRISMA guidelines, identifying 38 relevant case reports on spontaneous neck bleeding or haematoma caused by parathyroid adenomas from 1974 to 2020. Data included epidemiology, clinical features, and treatment. One patient treated at our clinic is described.

Results. Reviewing 38 articles, we found cervical haematomas from spontaneous bleeding of parathyroid adenoma in 45 patients, comprising 33 women and 12 men. Common symptoms were neck pain, dysphagia, and swelling. Surgery was the primary treatment, with 4.4% requiring tracheotomy. Average hospital stay was 12.5 days, which was mostly complication-free.

Conclusions. Parathyroid adenoma haemorrhage in middle-aged women with neck swelling, pain, and swallowing difficulty should be suspected. Diagnosis involves blood tests and contrast CT. Treatment is adenoma removal, typically without major complications.

Introduction

Parathyroid adenomas are benign neoplasms that are typically nonfunctional. Functioning adenomas, on the other hand, account for 90-95% of cases of primary hyperparathyroidism (PHP) 1. PHP has an incidence of 1/1000 and is more common in women than in men, particularly in the postmenopausal age 2. These lesions are usually oval or bean-shaped, reddish-brown in color, soft in texture, and have a bilobed or multilobulated appearance 3. Given that adenomas are relatively small, they are typically diagnosed through routine laboratory workup that reveals asymptomatic hypercalcaemia 4. Symptoms are numerous and diverse and surgical therapy is still the most effective treatment. Spontaneous haemorrhage of a parathyroid adenoma is a rare complication first described by Capps in 1934 5. The haemorrhage is usually confined to the capsule (intracapsular haemorrhage), but can occasionally spread beyond it (extracapsular haemorrhage), in which case it can compress adjacent structures such as the trachea and oesophagus, causing rapid and potentially fatal respiratory deterioration 6.

Diagnosis is usually not straightforward as the condition can mimic an inflammatory process and cause major bleeding when it occurs in the mediastinum 7. Even if haemorrhage remains a potentially fatal complication, the literature lacks a comprehensive description of the presentation, diagnosis and treatment of parathyroid adenoma, and only case reports or small series have been published to date.

We report a case of spontaneous haemorrhage of a parathyroid adenoma and perform a systematic review of the relevant literature with the aim of defining a clearer pattern of symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment for this condition.

Materials and methods

A comprehensive literature search was independently performed by two authors (AVM and SF). The PubMed, Google Scholar and Embase databases were searched according to the PRISMA guideline. Relevant English-language studies published from January 1974 to December 2021 were identified using the keywords “parathyroid adenoma”, “spontaneous cervical haemorrhage”, “spontaneous cervical haematoma”, “spontaneous rupture of parathyroid adenoma” and “functional parathyroid cyst”. The papers retrieved for the systematic review included 38 case reports and series presenting information about symptoms, imaging and treatment of the condition (Fig. 1). The patients’ epidemiological data, clinical and radiological features and treatments were recorded. Data including age, sex, symptoms, thyroid function, radiological findings, treatment and outcome of spontaneous haemorrhage of parathyroid adenoma were analysed. A case of a patient treated at our clinic is described. The patient provided informed consent for inclusion in this paper.

Case presentation

A 59-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with a 3-day history of a painful medial anterior neck swelling, odynophagia, progressive dysphagia, and fever (38°C). The patient’s blood tests, prescribed a few weeks before by her family physician, showed high parathyroid hormone (PTH) (203.1 pg/mL), low vitamin D (11 ng/dL), high calcium (11.7 mg/dL) and high phosphatase alkaline (126 U/L) levels. The patient denied any recent trauma. Her medical history included hiatal hernia, inflammatory bowel disease, chronic gastritis, and osteopenia with osteoporosis. The patient had undergone tonsillectomy when a child and a hysterectomy 10 years before presentation. She was not taking anticoagulants, antiplatelets, or other drugs, except vitamin D for osteopenia. She was allergic to iodised contrast media and had a family history of thyroid disease. On presentation, her white blood cells were 9.4 x 103/μL, haemoglobin 13.8 g/dL and C-reactive protein (CRP) 82.3 mg/L.

Diagnostic workup and therapeutic approach

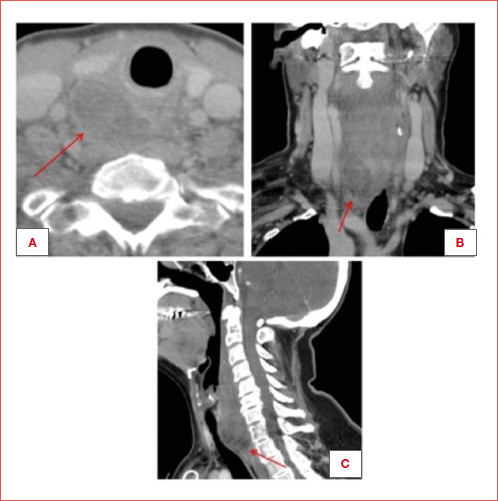

Fibroendoscopy was performed on admission with unremarkable results. Chest X-ray was negative. Neck ultrasound with color Doppler showed a Doppler-negative mixed-content mass measuring 3 x 2.5 cm in the retrothyroid area. A neck CT scan without contrast showed a well-marginated 3 x 2.5 cm (LL x CC) lesion in the median and right paramedian area, almost completely cleavable by the thyroid gland. Initially, conservative medical therapy was chosen. Treatment was started with cefotaxime 1g twice daily, metronidazole 500 mg four times daily and methylprednisolone 125 mg once daily. A neck CT with contrast was performed the following day, after treating the patient with an anti-allergy protocol. She showed a slight enlargement of the lesion (4 x 2.5 cm), with unchanged characteristics. It was therefore decided to perform an exploratory cervicotomy. During surgery, a cystic neoformation with haemorrhagic content was discovered posterior to the right thyroid lobe and easily excised from the thyroid tissue. A drain was placed at the end of the surgical procedure and removed two days later. Surgery was completed without complications. Two days later, haematological examinations were conducted, revealing a significant decrease in PTH levels, dropping from 203 to 87 pg/dL. Additionally, after two years, a blood sample was taken, showing a normal PTH value of 54.3 pg/mL. Laryngeal nerve function after surgery was preserved.

Histopathology

Definitive histological examination revealed a parathyroid adenoma with chief cells, characterised by solid and follicular architecture and widespread intralesional haemorrhage.

Outcome and follow-up

Two days after surgery, the patient’s CRP was 10.3 mg/L. Neither tracheotomy nor the insertion of a nasogastric tube was required. The patient was discharged 7 days after admission. At one-year follow-up the patient was in good health with no other medical problems.

Systematic review

Selected studies

Among the 38 articles included in this study, 31 were case reports, 2 case series, 4 case report reviews and 1 a case series review. The year of publication ranged from 1974 to 2020.

Epidemiology

Data for 45 patients were available. Geographic distribution was not always mentioned; only 7 articles reported the patient’s ethnicity (6 Caucasian and 5 Asian). Gender distribution showed a prevalence of women over men (33 vs. 12), with a mean age of 51 years (range, 29-81) for women and 54 years (range, 30-77) for men. The overall mean age was 53 years (range, 29-81).

In most cases, these were healthy patients: 13 (28.8%) had no other comorbidity, whereas no medical history was reported for 9 of 45 cases (20%). The most frequent comorbidities were kidney stones (3 patients, 6.6%), chronic renal failure (2 patients, 4.4%), and hyperparathyroidism (2 patients, 4.4%). Alcohol and cigarette consumption was reported for 5 of 45 (11.1%) patients, but not specified for the others (Tab. I).

Symptoms

All articles described the symptoms. The most frequently reported was neck pain (30 patients, 66.6%), dysphagia (22 patients, 48.8%), swelling (21 patients, 46.6%), ecchymosis (16 patients, 35.5%), dysphonia (12 patients, 26.6%), dyspnoea (12 patients, 26.6%), fever (7 patients, 15.5%), pharyngodynia (7 patients, 15.5%), and foreign body sensation (6 patients, 13.3%). Other less frequent symptoms are reported in Table II.

Laboratory tests

Pre- and post-treatment laboratory investigations were performed in all patients. The most frequently performed blood chemistry assays were calcium (mean value 10.8 mg/dL, range 17.3-8.2 mg/dL), PTH (mean value 244.8 pg/mL, range 41.4-994 pg/mL), PTHi (intact parathyroid hormone) (mean value 410.6 pg/mL, range 64-1500 pg/mL), Hb (mean value 11.4 g/dL, range 6.3-16.4 g/dL), P (phosphate) (mean value 3.1 mg/dL, range 6-1.5 mg/dL), albumin (mean value 4.3 g/dL, range 3.2-5 g/dL), alkaline phosphatase (mean value 166 U/L, range 60-380 U/L), creatinine (mean value 3.9 mg/dL, range 0.7-13.9 mg/dL), CRP (mean value 3.2 mg/dL, range 0.2-5.7 mg/dL) and CBC (complete blood count) (Tab. III).

Imaging

All patients underwent at least one radiological investigation. The most frequently used imaging was neck CT without contrast, performed in 27 patients (60%), followed by neck ultrasound (21 patients, 46.6%) and scintigraphy (17 patients, 37.7%). Other radiological investigations performed were neck CT with contrast (8 patients, 17.7%), neck MRI without contrast (5 patients, 11.1%), and chest X-ray (15 patients, 33.3%). Parathyroid adenoma was diagnosed with imaging in 6 of 45 patients (13.3%): specifically, with SPECT in 3 out of 6 cases (50%), CT with contrast in one of 6 cases (16.6%), CT without contrast in one of 6 (16.6%), and MRI without contrast in one of 6 (16.6%). In 23 of 45 cases (51.1%), only a haematoma was described on CT scan without contrast. In one case of 45 (2.2%), a parathyroid lesion was reported without specifying its nature. In 15 cases (33.3%), imaging was not conclusive.

Treatment

All patients received surgical or medical treatment, or both. Only one patient did not receive any type of treatment.

Timing and airway protection

As for surgical treatment, it should be noted that in 11 cases (24.4%) surgery was scheduled after resolution of the acute episode, and in 23 (51.1%) it was carried out as an emergency procedure. Four patients (8.8%) required emergency intubation and 2 (4.4%) required a tracheotomy. Tracheostomy duration was 7 days in one patient and not specified in the other.

The most commonly performed surgical treatment was exploratory cervicotomy (22 patients, 48.8%). In some cases, it was combined with thyroid lobectomy (2 patients, 9%) and parathyroidectomy (3 patients, 13.6%). Other types of surgical treatment included: median sternotomy (2 patients, 4.4%), thyroid lobectomy (one patient, 2.2%), parathyroidectomy (4 patients, 8.8%), parathyroidectomy with thyroid lobectomy (2 patients, 4.4%), hemithyroidectomy (2 patients, 4.4%), hemithyroidectomy with parathyroidectomy (one patient, 2.2%). In all surgical procedures performed, the search for recurrent laryngeal nerve was not mentioned except in 2 cases where it was described as an incidental finding near the mass 10,29 (Tab. IV).

Medical treatment, on the other hand, was mostly based on hydration, antibiotic therapy, and steroids. Four patients (8.8%) received antibiotic therapy alone. The duration of antibiotic treatment was reported in only one case (5 days). Eleven patients (24.4%) received both medical and surgical treatment.

Outcomes and follow-up

The average length of hospitalisation was 12.5 days (range 3-73), but these data were reported for only 15 patients. Most patients suffered no complications during the hospital stay, whereas recurrent nerve palsy was reported in 4 patients (8.8%). No patient required placement of a feeding tube, and all patients showed improvement in their condition after treatment. Only one death due to cerebral anoxia occurred. Follow-up was not mentioned, except for one case report, in which the reported disease-free interval was 13 years.

Discussion

Spontaneous bleeding of a parathyroid adenoma is a rare complication and only case reports or case series can be found in the literature. However, because it is a potentially fatal condition, accurate diagnosis and appropriate management are critical. In this review, we present a case report of a patient with spontaneous bleeding of a parathyroid adenoma and summarise the current findings reported in the literature. Our patient was a 59-year-old Caucasian woman with no significant comorbidities. According to the literature, the majority of patients affected by this complication are middle-aged women in good health 8-19. Although only 7 publications covered ethnicity, there does not seem to be any obvious ethnic predominance in terms of geographic distribution 15,19,24. This complication has a relatively vague clinical presentation, making the differential diagnosis often difficult. However, the main features reported in the literature were present in our case, given that she had pain, neck swelling, odynophagia, progressive dysphagia, and fever. Other symptoms are ecchymosis, dysphonia, dyspnoea, pharyngodynia, and foreign body sensation. There have been no reports of asymptomatic cases.

The diagnostic workup must include blood chemistry and radiological investigations. In our case, the patient had been examined by a general physician a few weeks prior to presentation and had been prescribed blood tests that showed high PTH, low vitamin D, high calcium and high alkaline phosphatase levels. On admission, we measured the inflammatory indices, which were 9.4 x 103/μL for white blood cells and 82.3 mg/L for CRP. All cases reported in the literature 1-38 also underwent pre- and post-treatment laboratory investigations, with a focus on calcium metabolism and inflammatory markers. The data indicate that when a parathyroid adenoma bleeds spontaneously, there is a rise in the levels of PTH, calcium, alkaline phosphatase, and CRP. The most common radiological examination was non-contrast CT 7,11-13,15-17,20-23,25,27-31,38-39,42,43. According to the published findings, SPECT is the most informative approach for patients developing this complication 18,29,41. Nevertheless, SPECT, which is not available in all medical facilities, was shown to be conclusive in only 3 of 17 cases 18,29,41, reflecting a very limited series. Therefore, the literature data show that contrast-enhanced CT is sufficient and quite reliable for the initial diagnosis. Other radiological investigations performed were non-contrast neck MRI, chest X-ray and neck ultrasound, none of which provided useful information for diagnosis or treatment. Even the most recent 3D techniques are not reported to provide additional information 44.

It should be noted that the final diagnosis is achieved through histological examination. As for treatment, initial conservative therapy with antibiotics and steroids is frequently mentioned 23,24,27,31,32,37. This approach is most likely the result of a delayed diagnosis. In our situation, medical treatment was given prior to the CT scan. In fact, the negative Doppler ultrasound and the absence of anaemia ruled out active bleeding, while the lack of fever and the relatively high inflammatory indices allowed for a watchful wait until the diagnosis was established. The literature describes some cases treated only with medical care. The authors suggesting this approach argue that haematomas can sometimes obscure normal anatomy, making identification of the adenoma more difficult and prompt surgical exploration risky. Another reason for not performing acute-phase surgery is the phenomenon of auto-parathyroidectomy, whereby spontaneous parathyroid bleeding can cause a temporary remission and sometimes even permanent control of hyperparathyroidism and its metabolic imbalances 13,29,41. In the latter scenario, surgery became unnecessary, and the patients did not undergo any operations. If the hyperparathyroidism persists, a delayed parathyroidectomy should be scheduled after the haematoma has reabsorbed. A minimum delay of 3 months has been proposed by Chaffanjon et al. in order to facilitate successful surgical treatment 13.

The exploratory cervicotomy performed in our patient revealed a cystic neoformation with haemorrhagic content that was excised from the posterior surface of the thyroid lobe. According to the literature, exploratory cervicotomy is the most commonly performed surgical procedure that results in resolution of the clinical picture in the majority of cases 7,10,11,16,17,19-21,23-25,28,30,32,36,37,39,42,43. In some instances, exploratory cervicotomy was performed in conjunction with thyroid lobectomy and parathyroidectomy, for two reasons: either because of the close anatomic relationships between the parathyroid adenoma and the surrounding tissue or because the exact site of origin of the haemorrhage could not be identified13,21,23,32,37. Because this complication could mimic a major haemorrhage or a mediastinal inflammatory process, a median sternotomy was described in 2 cases.

Tracheotomy is rarely needed; only 2 patients in the literature we reviewed required a tracheotomy for breathing difficulties. It has to be considered that due to the fact that this pathology is correlated to hyperparathyroidism, performing a parathyroidectomy should be considered in all cases in wich a cervicotomy is performed for the haemorrhage of the adenoma. As in our case, explorative cervicotomy with excision of the adenoma is usually free of complications; according to the literature, the most commonly reported sequela is unilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis (4 cases, 8.8%). The reported risk for recurrent laryngeal nerve injury after thyroid/parathyroid surgery varies among centres, with rates up to 38% 45,46. The rate is usually lower in some centres due to direct visualisation of the nerve and the use of intraoperative nerve monitoring, which reduce the incidence of nerve deficit to 1-2% 48. The need to place a feeding tube was not described in any case. In the articles analysed, follow-up was mentioned in only one case, lasting 13 years 23. In our case, clinical follow-up was regular, and a thyroid and parathyroid ultrasound scan performed 12 months after surgery showed no evidence of recurrence or other complications.

Conclusions

Spontaneous haemorrhage of a parathyroid adenoma should be considered, particularly in middle-aged, otherwise healthy women who present with neck swelling, pain, and difficulty in swallowing, with no other symptoms or signs observed during laryngoscopic examination. Blood chemistry tests are essential, with particular emphasis on calcium metabolism and inflammatory indices, which will often show increased levels of PTH, calcium, and alkaline phosphatase. A CT scan with contrast is usually sufficient for diagnosis. Today, the most appropriate radiological imaging for sensitivity and specificity in detecting parathyroid adenomas is 4-dimensional CT, first studied by Rodgers et al. in 2006 49. Once a correct diagnosis has been made, the primary treatment is surgical and involves an exploratory cervicotomy with removal of the adenoma; other surgical procedures are typically performed because of a lack of an accurate diagnostic process. In most cases, airway control is not necessary. If properly identified, spontaneous haemorrhage of a parathyroid adenoma can be resolved without sequelae or major complications.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

AVM, GT, PB: concept and draft; SF, KC, LB, SZ: data analysis and review; AVM, GT: final review.

Ethical consideration

No ethical committee approval is needed for reviews.

We confirm that the research was conducted ethically, with all study procedures being performed in accordance with the requirements of the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki.

Written informed consent was obtained from each participant/patient for study participation and data publication.

History

Received: April 22, 2024

Accepted: May 19, 2024

Figures and tables

Figure 1. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of the present study.

| Author | Year | Type | Patients | Sex | Age | Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berry 26 | 1974 | CR | 1 | M | 63 | ND |

| Santos 8 | 1975 | CR | 1 | F | 47 | ND |

| Jordan 32 | 1981 | CR | 1 | F | 38 | ND |

| Hotes 6 | 1989 | CR | 1 | F | 73 | ND |

| Simcic 38 | 1989 | CR | 1 | M | 32 | ND |

| Amano 25 | 1993 | CR | 1 | M | 64 | ND |

| Korkis 24 | 1993 | CR | 1 | F | 81 | Caucasian (1) |

| Hellier 9 | 1997 | CR | 1 | F | 52 | ND |

| Chin 28 | 1998 | CR | 1 | M | 37 | ND |

| Ku 19 | 1998 | CR | 1 | F | 80 | Asian (1) |

| Kovacs 35 | 1998 | CR | 1 | M | 49 | ND |

| Santelmo 10 | 1999 | CR | 1 | F | 63 | ND |

| Kozlow 11 | 2001 | CR | 1 | F | 48 | ND |

| Kihara 12 | 2001 | CR | 1 | F | 60 | ND |

| Shundo 37 | 2002 | CR | 1 | M | 50 | ND |

| Chaffanjon 13 | 2002 | CS | 4 | F (4) | 61* | ND |

| Tonerini 39 | 2004 | CR | 1 | M | 30 | ND |

| Kouloris 34 | 2006 | CR | 1 | F | 68 | ND |

| Nito 14 | 2007 | CR | 1 | F | 55 | ND |

| Shim 36 | 2008 | CR | 1 | F | 44 | ND |

| Merante-Boschin 15 | 2009 | CR | 1 | F | 56 | Caucasian (1) |

| Rehman 43 | 2010 | CR | 1 | F | 72 | ND |

| Whitson 42 | 2011 | CR | 1 | F | 49 | ND |

| Inokuchi 31 | 2011 | CR | 1 | M | 75 | ND |

| Huang J 16 | 2012 | CR | 1 | F | 56 | ND |

| Nagasawa 20 | 2012 | CR | 1 | M | 52 | Asian (1) |

| Yoshimura 7 | 2014 | CR | 1 | F | 47 | ND |

| Van den Broek 41 | 2015 | CR | 1 | F | 79 | ND |

| Ulrich 17 | 2015 | CR | 1 | F | 54 | ND |

| Ilyicheva 30 | 2015 | CR | 1 | F | 29 | ND |

| Shinomiya 21 | 2015 | CS | 2 | M (1), F (1) | 62, 76 | Asian (2) |

| Hanashiro 22 | 2017 | CR | 1 | F | 72 | Asian (1) |

| Garrahy 29 | 2017 | CR | 1 | F | 45 | ND |

| Carneiro de Sousa 27 | 2018 | CR | 1 | F | 74 | ND |

| Khan S 33 | 2019 | CR | 1 | F | 69 | ND |

| Uehara 40 | 2019 | CR | 1 | M | 77 | ND |

| Zammit 18 | 2020 | CR | 1 | F | 65 | ND |

| Tessler 23 | 2020 | CS | 4 | M (1), F (3) | 57, 59, 67, 75 | Caucasian (4) |

| Total | 45 | F:M = 2.7:1 | Mean age (range) | |||

| 53 (29-81) | ||||||

| CR: case report; CS: case series; ND: no data; M: male; F: female. *: the case series does not report the ages of all patients but only the mean. | ||||||

| Symptom | Number of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Neck pain | 30 (66.7%) |

| Dysphagia | 22 (48.9%) |

| Swelling | 21 (46.7%) |

| Bruising | 16 (35.6%) |

| Dysphonia | 12 (26.7%) |

| Dyspnoea | 12 (26.7%) |

| Fever | 7 (15.6%) |

| Pharyngodynia | 7 (15.6%) |

| Sense of foreign body | 6 (13.3%) |

| Odinophagy | 4 (8.9%) |

| Shortness of breath | 4 (8.9%) |

| Dry cough | 4 (8.9%) |

| Asthenia | 2 (4.4%) |

| Weight loss | 2 (4.4%) |

| Sialorrhoea | 2 (4.4%) |

| Myalgia | 2 (4.4%) |

| Cognitive dysfunction | 1 (2.2%) |

| Constipation | 1 (2.2%) |

| Dehydration | 1 (2.2%) |

| Dizziness | 1 (2.2%) |

| Diaphoresis | 1 (2.2%) |

| Otalgia | 1 (2.2%) |

| Polyuria | 1 (2.2%) |

| Polydipsia | 1 (2.2%) |

| Palpitations | 1 (2.2%) |

| Parameter | Mean value (range) |

|---|---|

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 10.8 (8.2-17.3) |

| PTH (pg/mL) | 244.8 (41.4-994) |

| iPTH (pg/mL) | 410.6 (64-1500) |

| Hb (g/dL) | 11.4 (6.3-16.4) |

| P (mg/dL) | 3.1 (1.5-6) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.3 (3.2-5) |

| Alkaline P (U/L) | 166 (60-380) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 3.9 (0.7-13.9) |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 3.2 (0.2-5.7) |

| PTH: parathyroid hormone; iPTH: intact PTH; Hb: haemoglobin; P: phosphate; CRP: C-reactive protein. | |

| No patients | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Exploratory cervicotomy | 22 | 48.8 |

| Partial excision of the thyroid gland (hemithyroidectomy/lobectomy) | 5 | 15.6 |

| Parathyroidectomy | 7 | 22.4 |

| Parathyroidectomy + partial excision of the thyroid gland (hemithyroidectomy/lobectomy) | 3 | 6.6 |

| Median sternotomy | 2 | 4.4 |

| Tracheotomy | 2 | 4.4 |

References

- Hammett-Stabler C, Maygarden S, Reisner H. Pathology: A Modern Case Study. McGraw-Hill; 2014.

- Haden S, Stoll A, McCormick S. Alterations in parathyroid dynamics in lithium-treated subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:2844-2848. doi:https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.82.9.4218

- Fialkow P, Jackson C, Block M. Multicellular origin of parathyroid “adenomas.” N Engl J Med. 1977;297:696-698.

- Silverberg S, Bilezikian J. Evaluation and management of primary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:2036-2040. doi:https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.81.6.8964825

- Capps R. Multiple parathyroid tumors with massive mediastinal and subcutaneous hemorrhage: a case report. Am J Med Sci. 1934;188:800-805.

- Hotes L, Barzilay J, Cloud L. Spontaneous hematoma of a parathyroid adenoma. Am J Med Sci. 1989;297:331-333. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00000441-198905000-00012

- Yoshimura N, Mukaida H, Mimura T. A case of an acute cervicomediastinal hematoma secondary to the spontaneous rupture of a parathyroid adenoma. Ann Thor Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;20:816-882. doi:https://doi.org/10.5761/atcs.cr.12.02060

- Santos G, Tseng C, Frater R. Ruptured intrathoracic parathyroid adenoma. Chest. 1975;68:844-846. doi:https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.68.6.844

- Hellier W, McCombe A. Extracapsular haemorrhage from a parathyroid adenoma presenting as a massive cervical haematoma. J Laryngol Otol. 1997;111:585-587. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022215100137995

- Santelmo N, Hirschi S, Sadoun D. Bilateral hemothorax revealing mediastinal parathyroid adenoma. Respiration. 1999;66:176-178. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000029364

- Kozlow W, Demeure M, Welniak L. Acute extracapsular parathyroid hemorrhage: case report and review of the literature. Endocr Pract. 2001;7:32-36. doi:https://doi.org/10.4158/EP.7.1.32

- Kihara M, Yokomise H, Yamauchi A. Spontaneous rupture of a parathyroid adenoma presenting as a massive cervical hemorrhage: report of a case. Surg Today. 2001;31:222-224. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s005950170172

- Chaffanjon P, Chavanis N, Chabre O. Extracapsular hematoma of the parathyroid glands. World J Surg. 2003;27:14-17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-002-6429-y

- Nito T, Miyajima C, Kimura M. Parathyroid adenoma causing spontaneous cervical hematoma: a case report. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2007;559:160-163. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03655230701600491

- Merante-Boschin I, Fassan M, Pelizzo M. Neck emergency due to parathyroid adenoma bleeding: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1947-3-7404

- Huang J, Soskos A, Murad S. Spontaneous hemorrhage of a parathyroid adenoma into the mediastinum. Endocr Pract. 2012;18:E57-E60. doi:https://doi.org/10.4158/EP11329.CR

- Ulrich L, Knee G, Todd C. Spontaneous cervical haemorrhage of a parathyroid adenoma. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2015;2015. doi:https://doi.org/10.1530/EDM-15-0034

- Zammit M, Siau R, Panarese A. Importance of serum calcium in spontaneous neck haematoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2020-23726719

- Ku P, Scott P, Kew J. Spontaneous retropharyngeal haematoma in a parathyroid adenoma. Aust N Z J Surg. 1998;68:619-621. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.1998.tb02117.x

- Nagasawa M, Ubara Y, Suwabe T. Parathyroid hemorrhage occurring after administration of cinacalcet in a patient with secondary hyperparathyroidism. Intern Med. 2012;51:3401-3404. doi:https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.51.8055

- Shinomiya H, Otsuki N, Takahara S. Parathyroid adenoma causing spontaneous cervical hematoma: two case reports. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1611-0

- Hanashiro N, Yamashiro T, Iraha Y. Non-traumatic rupture of the superior thyroid artery with concomitant parathyroid adenoma and multinodular goiter. Acta Radiol Open. 2017;6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/20584601177228

- Tessler I, Adi M, Diment J. Spontaneous neck hematoma secondary to parathyroid adenoma: a case series. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;277:2551-2558. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-05959-z

- Korkis A, Miskovitz P. Acute pharyngoesophageal dysphagia secondary to spontaneous hemorrhage of a parathyroid adenoma. Dysphagia. 1993;8:7-10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01351471

- Amano Y, Fukuda I, Mori H. Hemorrhage from spontaneous rupture of a parathyroid adenoma (a case report). Ear Nose Throat J. 1993;72:794-899.

- Berry B, Carpenter P, Fulton R. Mediastinal hemorrhage from parathyroid adenoma simulating dissecting aneurysm. Arch Surg. 1974;108:740-741. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.1974.01350290102019

- Carneiro de Sousa P, Gambôa I, Duarte D. Nontraumatic parapharyngeal haematoma: a rare lesion. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2018;2018. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7340937

- Chin K, Sercarz J, Wang M. Spontaneous cervical hemorrhage with near-complete airway obstruction. Head Neck. 1998;20:350-353. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199807)20:4<350::AID-HED10>3.0.CO;2-M

- Garrahy A, Hogan D, O’Neill J. Acute airway compromise due to parathyroid tumour apoplexy: an exceptionally rare and potentially life-threatening presentation. BMC Endocr Disord. 2017;17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-017-0186-2

- Ilyicheva E. Spontaneous cervical-mediastinal hematoma caused by hemorrhage into parathyroid adenoma: a clinical case. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;6C:214-7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2014.10.029

- Inokuchi G, Kurita N, Baba M. Retropharyngeal hematoma from parathyroid hemorrhage in a hemodialysis patient. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2012;39:527-530. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anl.2011.09.002

- Jordan F, Harness J, Thompson N. Spontaneous cervical hematoma: a rare manifestation of parathyroid adenoma. Surgery. 1981;89:697-700.

- Khan S, Choe C, Shabaik A. Parathyroid adenoma presenting with spontaneous cervical and anterior mediastinal hemorrhage: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000014347

- Koulouris G, Pianta M, Stuckey S. The ’sentinel clot’ sign in spontaneous retropharyngeal hematoma secondary to parathyroid apoplexy. Ear Nose Throat J. 2006;85:606-608.

- Kovacs K, Gay J. Remission of primary hyperparathyroidism due to spontaneous infarction of a parathyroid adenoma. Case report and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1998;77:398-402.

- Shim W, Kim I, Yoo S. Non-functional parathyroid adenoma presenting as a massive cervical hematoma: a case report. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;1:46-48. doi:https://doi.org/10.3342/ceo.2008.1.1.46

- Shundo Y, Nogimura H, Kita Y. Spontaneous parathyroid adenoma hemorrhage. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;50:391-394. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02913192

- Simcic K, McDermott M, Crawford G. Massive extracapsular hemorrhage from a parathyroid cyst. Arch Surg. 1989;124:1347-1350. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.1989.01410110109023

- Tonerini M, Orsitto E, Fratini L. Cervical and mediastinal hematoma: presentation of an asymptomatic cervical parathyroid adenoma: case report and literature review. Emerg Radiol. 2004;10:213-215. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10140-003-0317-0

- Uehara A, Suzuki T, Yamamoto Y. A functional parathyroid cyst from the hemorrhagic degeneration of a parathyroid adenoma. Intern Med. 2020;59:389-394. doi:https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.3319-19

- Van den Broek J, Poelman M, Wiarda B. Extensive cervicomediastinal hematoma due to spontaneous hemorrhage of a parathyroid adenoma: a case report. J Surg Case Rep. 2015;2015. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjv039

- Whitson B, Heckmann R, Manivel C. Acute airway compromise from a hemorrhagic posterior cervical-mediastinal mass: rare presentation of a parathyroid adenoma. J Thorac Dis. 2011;3:68-70. doi:https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2010.11.7

- Rehman H, Markovski M, Khalifa A. Spontaneous cervical hematoma associated with parathyroid adenoma. CMAJ. 2010;182. doi:https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.091167

- Tirelli G, de Groodt J, Sia E. Accuracy of the Anatomage Table in detecting extranodal extension in head and neck cancer: a pilot study. J Med Imaging (Bellingham). 2021;8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JMI.8.1.014502

- Jeannon J, Orabi A, Bruch G. Diagnosis of recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy after thyroidectomy: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63:624-629. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01875.x

- Mattsson P, Hydman J, Svensson M. Recovery of laryngeal function after intraoperative injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Gland Surg. 2015;4:27-35. doi:https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2227-684X.2015.01.10

- Tian H, Pan J, Chen L. A narrative review of current therapies in unilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve injury caused by thyroid surgery. Gland Surg. 2022;11:270-278. doi:https://doi.org/10.21037/gs-21-708

- Tirelli G, Bergamini P, Scardoni A. Intraoperative monitoring of marginal mandibular nerve during neck dissection. Head Neck. 2018;40:1016-1023. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.25078

- Rodgers S, Hunter J, Hamberg L. Improved preoperative planning for directed parathyroidectomy with 4-dimensional computed tomography. Surgery. 2006;140:932-940. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2006.07.028

Downloads

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright

Copyright (c) 2025 Società Italiana di Otorinolaringoiatria e chirurgia cervico facciale

How to Cite

- Abstract viewed - 332 times

- PDF downloaded - 127 times

PDF

PDF